ASHOK TO THE SYSTEM

Page 58

Page 59

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

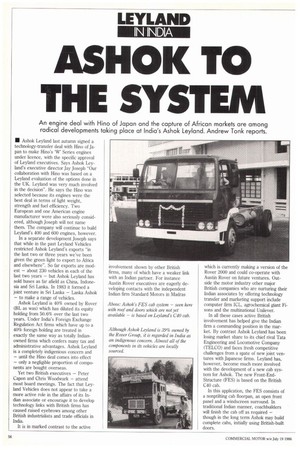

An engine deal with Nino of Japan and the capture of African markets are among radical developments taking place at India's Ashok Leyland. Andrew Tonk reports.

• Ashok Leyland last autumn signed a technology-transfer deal with Hino of Japan to make Hino's 'W' Series engines under licence, with the specific approval of Leyland executives. Says Ashok Leyland's executive director Jay Joseph "Our collaboration with Hino was based on a Leyland evaluation of the options done in the UK. Leyland was very much involved in the decision". He says the Hino was selected because its engines were the best deal in terms of light weight, strength and fuel efficiency. Two European and one American engine manufacturer were also seriously considered, although Joseph will not name them. The company will continue to build Leyland's 400 and 600 engines, however.

In a separate development Joseph says that while in the past Leyland Vehicles restricted Ashok Leyland's exports "in the last two or three years we've been given the green light to export to Africa and elsewhere". So far exports are modest — about 230 vehicles in each of the last two years — but Ashok Leyland has sold buses as far afield as China, Indonesia and Sri Lanka. In 1983 it formed a joint venture in Sri Lanka — Lanka Ashok — to make a range of vehicles.

Ashok Leyland is 40% owned by Rover (BL as was) which has diluted its equity holding from 50.6% over the last two years. Under India's Foreign Exchange Regulation Act firms which have up to a 40% foreign holding are treated in exactly the same way as totally Indianowned firms which confers many tax and administrative advantages. Ashok Leyland is a completely indigenious concern and — until the Hino deal comes into effect — only a negligible proportion of components are bought overseas.

Yet two British executives — Peter Capon and Chris Woodwark — attend most board meetings. The fact that Leyland Vehicles does not appear to take a more active role in the affairs of its Indian associate or encourage it to develop technology links with British firms has caused raised eyebrows among other British industrialists and trade officials in India.

It is in marked contrast to the active which is currently making a version of the Rover 2000 and could co-operate with Austin Rover on future ventures. Outside the motor industry other major British companies who are nurturing their Indian associates by offering technology transfer and marketing support include computer firm 1CL, agrochemical giant Fisons and the multinational Unilever.

In all these cases active British involvement has helped give the Indian firm a commanding position in the market. By contrast Ashok Leyland has been losing market share to its chief rival Tata Engineering and Locomotive Company (TELCO) and faces fresh competitive challenges from a spate of new joint ventures with Japanese firms. Leyland has, however, become much more involved with the development of a new cab system for Ashok. The new Front-EndStructure (FES) is based on the British C40 cab.

In this application, the FES consists of a nonptilting cab fioorpan, an open front panel and a windscreen surround. In traditional Indian manner, coachbuilders will finish the cab off as required — though in the long term Ashok may build complete cabs, initially using British-built doors. Ashok Leyland's latest financial results — issued in March — show pre-tax profits slipping from 23.7 million in 1984 to 22.5 million in 1985 even though turnover increased from 2161 million to £191 million. The divident was slashed from the 18% paid in the previous three years to just 10%.

There are longer-term problems too. In 1980 Ashok Leyland prepared an ambitious expansion plan with the intention of making 40,000 vehicles by 1987. Last year it made around 16,000 vehicles, split equally between bus and truck chassis. Joseph says the new plan is to make 25,000 vehicles a year by 1990. He says that in the late 1970s the Indian truck market expanded very rapidly which raised hopes. By comparison demand in the early 1980s was stagnant. Also he speculates that long haul traffic — using the heavy trucks made by Ashok Leyland — did not increase at the same rate as intra-state movements, while many local urban transport corporations were short of funds to purchase new buses.

That does not account for Ashok Leylands falling market share. In the last five years (1981-1985) its share of the Indian market for medium and heavy commercial vehicles (which in India mostly 12 tonne gross vehicle weight trucks and heavy duty buses) averaged 23.6%, down from 25.8% in the previous five years. By contrast Telco managed to strengthen its position from 68.6% to 72.6% over the last decade, taking sales from Ashok Leyland and other smaller producers. Telco's trucks are 10-15% cheaper, but Ashok Leyland claims its are more robust.

Moreover the effective duopoly of Telco and Ashok Leyland has come to an end. Hindustan Motors — which still makes a version of the 1950s Morris Oxford car called the Ambassador — is reentering the truck market in collaboration with Isuzu of Japan. It intends to bring out a heavy truck later this year and a light commercial vehicle next year. This is why one of the recent Japanese joint ventures set up in India.

Mazda, Mitsubishi, Nissan and Toyota have all formed joint ventures with Indian companies each with a capacity to make betwen 10,000 and 15,000 light corrunercial vehicles each year. Suzuki is also collaborating with India's biggest car maker Maruli Udgog to make a utility vehicle. They join a market already supplied by three Indian firms — Bajaj Tempo, Mahindra & Mahindra and Standard Motors. At present the market for light commercial vehicles in India is only around 30,000/year, compared to a market for medium and heavy commercial vehicles of 63,000/year.

But that could change, Telco's executive director A N Maira notes that in the past many truck operators have used heavy vehicles for jobs suited to light vehicles because they did not have a choice of affordable lightweight vehicles. He notes the Telco's market research shows that the fastest growth in demand will be for lighter vehicles. So in February Telco luanched its "407", 4.8tonne, light commercial vehicle to compete with the Japanese joint venture companies,

Ashok Leyland has brought out an 8tonne vehicle, but Jospeh says it will concentrate on heavier vehicles. The Hino 'W' series engines — from 45-135kW — will eventually be fitted in most Ashok Leyland vehicles, and will also be built for non-automotive applications. Ashok Leyland is a major engine supplier. It has been successful in selling to the marine equipment market and recently won a prestige contract to supply engines for the Indian Army Shaktiman trucks.

In its mainstream businesses Joseph is confident that Ashok Leyland can regain ground. He stresses that the bus business should expand rapidly thanks to India's rapid urbanisation. At the last Indian motor show it unveiled a semi-integral, rear-engine luxury coach and also displayed some of its multi-axle vehicles built for specialist uses.

Ashok Leyland could make its own major foreign collaboration in the next few years. Joseph says it is having preliminary talks with various foreign firrns for cooperating to make earth-moving machinery and other off-road vehicles.

Despite the increasingly competitive market the demand for commercial vehicles is expected to increase sharply in India. Recent government policy decisions indicate that foreign competition will be strictly circumscribed, giving Ashok Leyland a major stake in the future. The government's latest five-year plan assumes that demand for commercial vehicles will double to almost 200,000/year by 1990. Some industry observers admit such targets will not be met on time, but few doubt that India is one of least exploited auto markets in the world.

It remains to be seen whether Leyland Vehicles will leave Ashok very much to its own devices, or whether projects such as the FES point the way to a new form of relationship between Leyland and its Indian associate.