The phrase "Toyo Kogyo one-tonne pickup" sounds like some sort

Page 32

Page 33

Page 34

Page 35

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

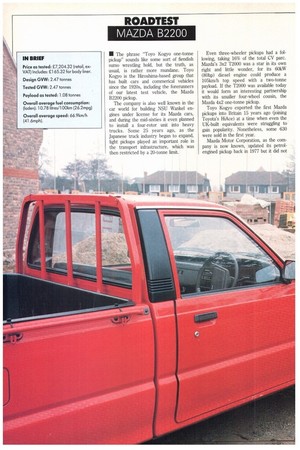

of fiendish sumo wrestling hold, but the truth, as usual, is rather more mundane. Toyo Kogyo is the Hiroshima-based group that has built cars and commerical vehicles since the 1920s, including the forerunners of our latest test vehicle, the Mazda B2200 pickup.

The company is also well known in the car world for building NSU Wankel engines under license for its Mazda cars, and during the mid-sixties it even planned to install a four-rotor unit into heavy trucks. Some 25 years ago, as the Japanese truck industry began to expand, light pickups played an important role in the transport infrastructure, which was then restricted by a 20-tonne limit. Even three-wheeler pickups had a following, taking 16% of the total CV parc. Mazda's 3x2 T2000 was a star in its own right and little wonder, for its 60kW (80hp) diesel engine could produce a 105km/h top speed with a two-tonne payload. If the T2000 was available today it would form an interesting partnership with its smaller four-wheel cousin, the Mazda 4x2 one-tonne pickup.

Toyo Kogyo exported the first Mazda pickups into Britain 15 years ago (joining Toyota's HiAce) at a time when even the UK-built equivalents were struggling to gain popularity. Nonetheless, some 630 were sold in the first year.

Mazda Motor Corporation, as the company is now known, updated its petrolengined pickup back in 1977 but it did not introduce the diesel version until 1985.

It uses the same R2 naturally-aspirated 2.2-litre engine as the E2200 panel van, with a near-identical driveline and suspension. In recent years, the pickup has fared much better than the van, becoming a mainstay of self-employed building tradesmen and agricultural workers.

Last year the market sector was an exceptional one for the dealers, with sales up 51% on 1987 (higher still if four-wheel drive versions are taken into account). Of course, Mazda does not have a 4X4 version — yet.

Although only fourth in the 4x2 pickup sales league, the Mazda clearly has its own dedicated following, quotas permitting, registering 1,302 last year (about 30% of them diesels). This gives it 10% of a market sector which is dominated by the (so far) petrol-only Ford P100's near40% share, and the Peugeot 504's 24%. For such a well-established tool of the trader, the B2200 is a curious mixture of contrast and compromise, giving a very good payload and fuel-efficient performance, marred by erratic ride and handling characteristics that are overly dependent on the load carried.

• BODYWORK

Mazda has stayed with its traditional three-piece arrangement of a cab and load box mounted separately onto a boxsection ladder-type frame. From the front the bodywork has a stocky, durable look with a deep windscreen and oblong headlamps recessed into a hefty steel bumper. Styling innovations include a refashioned front grille and Cortina-type flaring along the sides.

The business end, made from swaged steel, lives up to its functional appearance. Unladen, the double-skinned load bed stands nearly a metre high, with wheel boxes that are intrusive enough to allow adequate deflection of the multi-leaf springs when carrying its maximum load.

Lashing rings and cleats run along the sides, and the sturdy plastic-lined tailgate lets down via a single catch onto two folding stays. It is strong enough to allow the driver to climb on and drag cargo to the rear for unloading. A useful ladder rack comes as standard, with lifting end brackets to prevent a load sliding off.

One of the Mazda's main selling points is its 2,270mm load bed which, with the exception of the Isuzu-built Bedford Brava (née KB) pickup, is the longest in its class. Complete with optional plastic bed liner, which costs 2165.32, the B2200 offers a respectable 1,080kg payload.

• DRIVELINE

Mazda's naturally-aspirated IDI R2 diesel may not be as advanced as some of the 2.5-litre DI units on the market, but at 160kg it is one of the lightest around and is relatively easy to maintain.

Main and bypass oil filters are easily accessible from the top, as is the fuel filter. Dirt or water en route to the tank will first collect in a sedimentor bowl set outside the chassis frame, ahead of the offside rear wheel. Valves can be adjusted without disturbing the camshaft, and valve springs and oil seals changed with the cylinder head in situ. Care and maintenance of the Kiki Diesel fuel-injection equipment is covered by a sales and service agreement with Bosch, through Mazda's UK dealer network.

The 2.2-litre IDI engine delivers 48kW (64hp) at 4,250 rpm and 130Nm at 2,000rpm, which compares favourably with the market leading diesel-engined pickup: Peugeot's 2.3-litre unit in the 504 delivers a smidgin more power (51.1kW) at a slightly higher 4,500rpm.

The B2200 uses the same two-piece propshaft with centre support bearing, five-speed synchromesh gearbox and single-reduction axle as Mazda's E2200 panel van, but with ratios more suited to a mix of road and site work.

Given that it has slower gearing than the van, the fully-laden pickup produced quite good economy around our 1371cm Kent light van test route, returning 10.78litres/100km (26.2mpg) at an average speed of 66.9km/h (41.6mph). When empty it returned an excellent 8.19litres/ 100km (34.5mpg).

The R2 engine is powerful and flexible enough, but on the test track, its output seemed peaky, falling off as revs fell — acceleration seemed dismal compared with some of the others. From 0-80km it was five seconds behind the 504 and only just ahead of the Dacia Duster.

Through the gears it lagged behind them all and on steep hills it failed to impress until the lower gears were selected, when it showed real bite. On gradeability the B2200 is second to none, restarting very easily on the 25% (1-in-4).

Such is the gear spread that when it is fully laden there seems to be insufficient gears, accentuating the big gaps between 2/3 and 3/4th gears, thus encouraging the use of high revs to maintain enough speed to keep up with normal town traffic. Without a load, first and second gears are surplus to requirements, apart from moving off from rest.

The gears select very smoothly indeed, helped by a light hydraulically-operated clutch, but is is the suppleness of the suspension that causes concern, particularly at speed. Unladen it lacks the tail-up attitude of the Peugeot 504, but the ride is indeed lively, with very soft torsion-barassisted independent front suspension and a stiffer rear end which tends to skip around. Hard braking on irregular surfaces can catch out the unwary.

We followed Mazda's recommendation of increasing the rear tyre pressures from 1.8 to 4.3 bar (34 to 63psi) when loading up to its maximum GVW: this certainly made it more docile and reduced some of the excessive roll too.

Nonetheless at 2.47 tonnes the multileaf rear springs felt close to their limit and the tail end wallowed, especially when driven hard around corners. Not surprisingly, the ideal ride condition occurs when the B2200 is just less than half laden with a well distributed load.

The long-term Renault's Traffic test is now completed, and its place is being taken by this Mazda. For most of the time it will be driven around by us part-laden, as would be the case in service, and reported on accordingly.

It is easy enough to balance tyres when necessary, but there should be provision in the cab for the driver to alter the headlight beam height too. Some manufacturers, such as Scania, fit a control for this purpose: in the interests of greater safety it should be made mandatory. Mazda please note.

Unlike Mazda's panel van, with its rack and pinion steering, the B2200 uses a recirculating-ball steering box which feels quite positive even when fully laden. Excessive weight at the front does make it feel heavier, but the axle loadings allow a useful tolerance of 120kg and LCV oper ators should take full advantage of this.

Track tests revealed the left rear wheel to be locking up but brake efficiencies are quite high, and stopping distances reasonable. There was no doubting the umbrellahandled park brake which acts on the rear wheels only: it held the laden pickup on the 33% (1-in-3) slope facing up and downhill with consumate ease.

• INTERIOR

Entry to the cabin is easy as the doors are wide and the threshold level with the floor pan. Bench-type seats are uncompromising with little or no adjustment. They also have a habit of sagging at the edges, which is not condusive to driver comfort. The example in our test vehicle has good shape and is quite firm at the moment, but the backrest is too hard and there is little in the way of lumbar support. Good bucket seats similar to those used in the Transit would be a better proposition and would also provide some much-needed storage space.

If the driver is short there will be room behind the seat for a small case, but loftier types will need all the leg room they can get, pushing the seat to the rear. If the glove box was the same width as its lid, it would be more useful, and the storage compartments on top and in the centre console are too shallow to be of much use.

Instrumentation is simple and functional with fuel and temperature gauges set either side of the rising-sun speedo which lacks a trip meter.

The strip of warning lights beneath it includes one with a buzzer which tells the driver that the sediment bowl is fully contaminated. Stalk switches for the lights and windscreen wipers are unobtrusive and easy to use but they are positioned in the old imperial way. This may suit the Japanese, but for us are the wrong way around. An intermittent wipe would also be better than the single, push wipe movement.

The heating/ventilation system looks impressive and is efficient most of the time with rotary temperature and (fourspeed) fan switches with an array of vents. On cold mornings the diesel engine takes its time warming up, so it also takes that much longer to defrost the interior, particularly the rear window. Once normal temperatures are reached fresh air at face level with a heated footwell is only possible with a window open.

The Mazda's plasticky inner trim is a mixture of sombre greys, looks very neat, and is wipe-clean but leaves the driver in no doubt as to its origins. This is brought home quickly on a frosty morning start when the chill from the cheap seat covering strikes upwards like a surgeon's knife.

There are some neat touches though, such as the plastic sleeve on the bonnet stay and the tray under the bypass filter to ensure oil does not run down the engine block but can be collected. It seems odd, however, that these inscrutible oriental designers should fit squeeze clips onto water hoses, and screw-type jubilee clips onto the air ducting.

• SUMMARY

The sturdy Mazda B2200 is certainly full of Eastern promise. It has a long load bed, a useful one-tonne-plus payload, excellent gradeability and gives a good return on fuel.

Apart from its rather unprogressive suspension, which affects its handling somewhat, it is easy to drive although too wide a spread of gears makes it feel rather lifeless when fully laden.

The cab is plain and functional but the uncompromising bench seat is pointless in that there is neither room nor seatbelt for a third passenger. Further evidence of value engineering is the omission of an interior light switch for the left hand door.

Except for the Dacia, which at 23,625 is half the price of the 504, the B2200 is one of the lowest in cost in this sector, retailing at 27,039 — that is 2900 less than the market-leading P100, 2170 below the 504 and on a par with the Bedford Brava. The Nissan contender, which takes 13.4% of the UK pickup market, costs another 21,300.

Any jobbing tradesman looking to replace his clapped-out pickup should take a close look at the Mazda, which certainly gives value for money.

by Bryan Jarvis