Vehicle maintenance diy or contract out?

Page 46

Page 47

Page 48

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

1HE NATIONWIDE commercial breakdown recovery services will tell you that some lorries are rather better maintained than others. The client-by-client call-out records clearly show it.

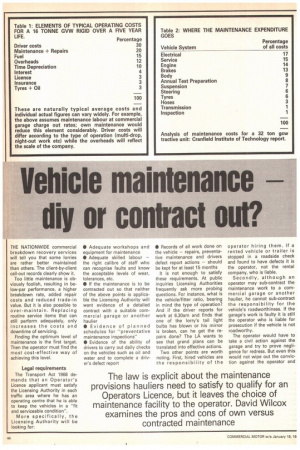

Too little maintenance is obviously foolish, resulting in below-par performance, a higher breakdown rate, added repair costs and reduced trade-in value. But it is also possible to over-maintain. Replacing routine service items that can still perform adequately, only increases the costs and downtime of servicing.

Finding the optimum level of maintenance is the first target. Then the operator must find the most cost-effective way of achieving this level.

Legal requirements

The Transport Act 1968 demands that an Operator's Licence applicant must satisfy the Licensing Authority in each traffic area where he has an operating centre that he is able to keep the vehicles in a "fit and serviceable condition".

More specifically, the Licensing Authority will be looking for: • Adequate workshops and equipment for maintenance • Adequate skilled labour — the right calibre of staff who can recognise faults and know the acceptable levels of wear, tolerances, etc.

• If the maintenance is to be contracted out so that neither of the above points is applicable the Licensing Authority will want evidence of a detailed contract with a suitable commercial garage or another haulier • Evidence of planned schedules for "preventative maintenance inspections" • Evidence of the ability of drivers to carry out daily checks on the vehicles such as oil and water and to complete a driver's defect report • Records of all work done on the vehicle — repairs, preventative maintenance and drivers defect report actions should be kept for at least 15 months It is not enough to satisfy these requirements. At public inquiries Licensing Authorities frequently ask more probing questions. For instance, what is the vehicle/fitter ratio, bearing in mind the type of operation? And if the driver reports for work at 6.30am and finds that one of the lorry's tail light bulbs has blown or his mirror is broken, can he get the repairs done? The LA wants to see that grand plans can be translated into effective actions.

Two other points are worth noting. First, hired vehicles are the responsibility of the operator hiring them. If a rented vehicle or trailer is stopped in a roadside check and found to have defects it is the operator, not the rental company, who is liable.

Secondly, although an operator may sub-contract the maintenance work to a commercial garage or another haulier, he cannot sub-contract the responsibility for the vehicle's roadworthiness. If the garage's work is faulty it is still the operator who is liable for prosecution if the vehicle is not roadworthy.

The operator would have to take a civil action against the garage and try to prove negligence for redress. But even this would not wipe out the conviction against the operator and the black mark against his Operator's Licence.

So Operator Licensing is fairly specific about the standard of maintenance arrangements it expects. This can be carried further; the Department of Transport gives operators a good idea of what it requires of the individual vehicle. The Department of Transport produces the Goods Vehicle Tester's Manual which goes through, point-by-point, what the official heavy goods vehicle test stations are examining. For operators wanting to minimise the chance of faking the annual test this manual (which was revised last year) is essential reading.

Of the 723,000 lorries that were submitted for the annual hgv test in the year 1983/84, over 22 per cent of them failed at the first attempt. And almost nine per cent of those taking retests failed again.

With the law establishing the minimum standard of vehicle maintenance and condition the operator can adjust the level upwards to suit his own needs. The costs and repercussions of a breakdown on the road will figure largely in the decision. Experience shows that even averagely-maintained lorries have a 25-30 per cent chance of needing roadside assistance during the year.

Having decided on the optimum level of maintenance an operator can then concentrate on how to achieve it at the lowest cost.

Own maintenance Theoretically, own maintenance should be the cheapest option — the operator does not pay for a garage's profit, better still has complete control. Factors such as the cost and utilisation of workshops, fitters and equipment usually dictate that an operator can only consider setting up his own workshop if he has a fleet of at least 10-15 vehicles. The largest area of savings with in-house maintenance is the reduced cost of labour. A commercial garage will typically be looking to make a 50 per cent profit from his hourly labour charge-out rate.

Downtime should also be reduced because the vehicle can be operated right up until it is time to go over the pit. Garages tend to think in complete days when it comes to calling in and releasing vehicles.

Own-maintenance also means that you have fitters when and where you need them — you can provide cover for the early starts.

An operator with his own maintenance set-up also has control over the quality of parts and consumable items used, such as oil. And from close analysis of the parts and labour he can learn a lot about the operating costs of his various vehicles.

The range of computer-based monitoring and recording packages (or bureau services for the smallest operators) now available means that this last advantage can be really effective.

Some companies, among them Bass UK, have adopted the Institute of Road Transport Engineers' VMRS (vehicle maintenance record system) in an effort to monitor and reduce inhouse maintenance costs. The allocation of numerical codes to the parts of a vehicle enables VMRS to help the operator monitor and allocate costs precisely.

Bass regularly samples and analyses the engine oil and, by delaying replacement until the oil can no longer perform to its specification, the company reports that it has significantly reduced lubrication costs.

Bass has identified brake maintenance expenditure as an area worthy of close scrutiny, representing 16 per cent of total maintenance costs, and this year is looking more specifically at where the brake costs arise and how they can be cut.

Logically, good in-house maintenance should be the best method of keeping the vehicles in peak condition. But if poorly done it will not be cost effective and can hide inefficiencies and wastage. Money tied-up in stocks of spares and little-used equipment could be working more profitably elsewhere in the business.

Contracted-out maintenance

An operator who cannot, or chooses not to, do his own maintenance has quite a choice of alternatives. He can go to the local commercial garage or dealer, to another operator who is equipped to take in outside work, to one of the specialist nationwide contract maintenance companies or take out a repair and maintenance contract with the vehicle manufacturer when he buys the lorry.

The least sophisticated of these methods is to use the local commercial garage, booking in the vehicle when servicing or repairs are needed. The operator will still need to remember to make the bookings and to prepare and submit the vehicle for annual testing. Downtime and dead mileage will inevitably be greater than with in-house maintenance. Labour charge-out rates will be higher but customers of a franchised dealer will have manufacturer's prescribed workshop times as a guide. Product knowledge and tailormade tools should help keep franchised dealers' times down.

Many small hauliers and owner-drivers entrust their maintenance to a larger operator nearby who takes in outside work to boost the utilisation of its own workshops. The labour rate should undercut the dealer's, but the smaller operator needs to establish what priority his vehicles will be given when they are waiting for servicing alongside one of the large operator's own vehicles. Money saved on labour can be lost again in extra downtime.

The ideal operator to whom to entrust the work would run the same make of vehicles as the customer. Its workshops will have the expertise, experience and stock of spares.

When he buys a new lorry an operator can now opt to take out a maintenance contract for it which is rather more comprehensive than merely booking the vehicle in for a service.

The contract may be either with the manufacturer (the local dealer is nominated to do the work) or directly with the dealer. Either way, the dealer does the preventative maintenance inspections, the manufacturer's prescribed servicing, repairs, annual test preparation and submits the vehicle for the test. Thus the dealer takes on part of the operator's administrative job, issuing reminders and calling in the vehicle at the appropriate time.

This is in the same mould as contract hire, relieving the operator from an increasing part of the task of running vehicles, and is seen as a growth area by vehicle manufacturers and dealers.

Their enthusiasm is easy to understand. In recent years a depressed commercial vehicle market and greater discounting has squeezed profit margins on new vehicle sales and dealers' workshops have become an increasingly important source of income. They earn less than sales but show a healthier margin. For example, a fairly typical dealer told me that the percentage profit on new vehicle sales is in single figures while his workshop labour charges are earning nearer 50 per cent profit.

The work also generates spares sales which are also a good earner around 20 per cent profit said the dealer. Manufacturers are keen to develop the idea to boost their genuine parts operation and to put more business in the direction of their dealers, thereby strengthening the network.

A step further down the road in this direction are the national companies that have really promoted the principle of contract maintenance. A good example is Fleetcare, the National Freight Consortium company. Its name used to be prefixed by National Carriers but that has now been dropped.

Fleetcare came under BRS on January 1 this year although it has established a separate identity. It was started to use spare capacity in National Carriers depots, but has since blossomed into a business on its own with a £22m turnover on maintenance and service, not including spares sales.

About one third of Fleetcare business is still from National Carriers. Another third is from its major contract customer British Rail, while the remaining third is with other outside customers, typically operators with five to 10 vehicles.

Fleetcare adopts the complete maintenance package approach with reminders, test submission, and managemen information. Its labour charge i between nine and E10 an hou in the provinces, rising to £1 and £14 in central London. Fc the larger national customer an overall, flat rate would b offered.

The company claims that a most any type of vehicle can b maintained at Fleetcare depot: providing "one-stop" servicin for mixed fleets and, hence, eE. sier administration.

Avoidance of downtime is a attractive proposition and s Fleetcare offers servicing du ing the night at some branche To capitalise on parts sale Fleetcare is setting up sever; parts-only centres fo operators.

NFC sister company BR offers servicing for othE operators on either a contrao tual or casual basis at its 13 branches in England an Wales. Under the title of BR Engineering, this aspect of th branches' work is not a strongly promoted as FleetcarE Using a similar principle bo with a pure contract hire an rental business as the foundh tion, Transfleet Services hE also thrown open its nine do pots' workshops to outside cu: tomers. Its Morley depot ne Leeds typifies how an in-hous maintenance operation, viewe by some as a cost-centre, ca be turned into a generator < profits by inviting outside bus ness. It offers 24-hour servicino

it is an official tachograph st tion and holds the British Le,

and Multipart franchise for tlLeeds area.