Opening the Nigeria route—a great potential for British hauliers

Page 34

Page 35

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

by Patrick Prekopp

IT'S a 2,000-mile round-trip of hell! That's the verdict of one of the first haulage pioneers to cross the African continent on the newly opened Nigeria route.

Through hundreds of miles of tyre-melting sand, across foothigh road corrugations, sweltering in temperatures above 130 degrees Farenheit, and travelling often at speeds of less than lOmph, the five-truck convoy of Thomas Bone (Shipping) Ltd, from Kilmarnock in Scotland, ploughed into the unknown.

For days, all that they could see was the mangled wreckage of abandoned vehicles—a grim warning of the price to pay for being unprepared.

But four weeks later, "miraculously" without accident or illness, the convoy pulled into Kano and delivered its load.

Fabulous

"It was a fabulous experience," said Torn Bone. "Although it drained us of every bit of mental and physical energy we had, it was worth it. There's a great poten tial in Nigeria for British hauliers; we've already had several inquiries from big businesses. Any amount of cargo can be got—it's getting it there that counts."

As from January next year, Tom Bone will be setting up a regular monthly run to Kano. It's a decision not lightly taken. For as a veteran of the gruelling Mid-East route, which is "like a Sunday afternoon stroll" after Africa, he is now aware of the hazards.

"It's not a run I would recommend to anyone who hasn't been on the Middle East route. The conditions are so much worse and the risks of a costly breakdown so much greater that only fully equipped trucks and the best drivers will get through," added Mr Bone.

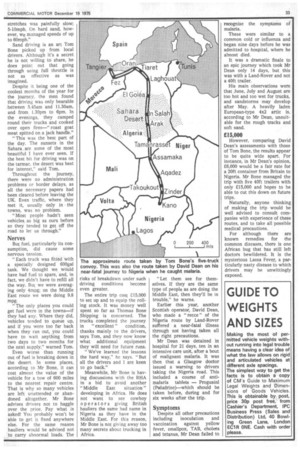

The convoy of four Scanias and one Volvo set out from Southampton in October, and using the Michelin recommended route — Tangier, Algiers, the Sahara desert, Nigeria—began their "journey through hell."

None of the trucks was specially converted; standard UK sleeper cabs fitted with double-skin sunroofs and air conditioning blowers. Running at 40 tons gross weight, and with 401t trailers, they met their first obstacle a couple of hundred miles south of Laghouat, Algiers, where the tarmac ended and the desert began.

Precautions

Although every precaution had been taken in checking the vehicles, that each of the eight drivers was adequately inoculated and that they had every authorisation for carrying the loads across the borders, none of them was ready for the muscle-straining ride ahead.

For stretches of 300 miles at a time, the convoy humped itself over 9in to 121n corrugations which •then levelled out for 200 miles of slipping, scorching sand. At Arak, in the desert, the road was solid, slate-like ridged rock which knifed into the tyres.

The trailers were being thrown a foot into the air. It sounded like thunder going through the desert," said Tom.

"At several points, the convoy was held up for two or three days, the time it took to dig out a truck buried in the sand.

"Progress along these stretches was painfully slow; 5-10mph. On hard sand, however, we managed speeds of up to 60mph."

Sand driving is an art Tom Bone picked up from local drivers. Although it's a secret he is not willing to share, he does point out that going through using full throttle is not as effective as was imagined.

Despite it being one of the coolest months of the year for the journey, the men found that driving was only bearable .between 5.45am and 11.30am, and from 1.30pm to 6pm. In the evenings, they camped round their trucks and cooked over open fires—" roast goat meat spitted on a jack handle."

"This was the best part of the day. The sunsets in the Sahara .are some of the most beautiful I have ever seen. If the best bit for driving was on the tarmac, the desert was best for interest,' said Tom.

Throughout the journey, there were no administration problems or border delays, as all the necessary papers had been cleared before leaving the UK. Even traffic, where they met it, usually only in the towns, was no problem.

"Most people hadn't seen vehicles as big as ours before so they tended to get off the road •to let us through."

Nerves

But fuel, particularly its consumption, did cause some nervous tension.

"Each truck was fitted with a specially designed 600gal tank. We thought we would have had fuel to spare, and, in fact, we didn't have to refill all the way. But we were averaging only 4mpg; on the Middle East route we were doing 9.8 mpg.

"The only places you could get fuel were in the towns—if they had any. Where they did, vehicles tended to queue up, and if you were too far back when they ran out, you could have to wait anything from two days to two months for the next supply," warned Tom.

Even worse than running out of fuel is breaking down in the desert. In some places, according to Mr Bone, it can cost almost the value of the vehicle for a tow of 600 miles to the nearest repair centre. That is why so many vehicles are left unattended or abandoned altogether. Mr Bone advises drivers not to haggle over the price. Pay what is asked! You probably won't be able to get it fixed anywhere else. For the same reason hauliers would be advised not to carry abnormal loads. The risks of breakdown under such driving conditions become even greater.

The entire trip cost £15,000 to set up and to equip the rolling stock. It was money well spent so far as Thomas Bone Shipping is concerned. The trucks completed the journey in " excellent " condition, thanks mainly to the drivers, says Tom, and they now know what additional equipment they will need for future runs.

"We've learned the lessons the hard way," he says. "But all the drivers and I are keen to go back."

Meanwhile, Mr Bone is having discussions with the RHA in a bid to avoid another "Middle East situation" developing in Africa. He does not want to see cowboy operators giving British hauliers the same bad name in Nigeria as they have in the Middle East. For this reason, Mr Bone is not giving away too many secrets about trucking in Africa. "Let them see for themselves. If they are the same type of. people as are doing the Middle East, then they'll be in trouble," he warns.

Earlier this year, another Scottish operator, David Dean, who made a " recce " of the Nigeria route by Land-Rover suffered a near-fatal illness through not having taken all the right precautions.

Mr Dean was detained in hospital for 21 days, ten in an intensive care unit, after a bout of malignant malaria. It was then that a Glasgow doctor issued a warning to drivers taking the Nigeria road. This included •a course of antimalaria tablets — Proguainl (Paludrine)—which should be taken before, during and for six weeks after the trip.

Symptoms

Despite all other precautions including inoculation and vaccination against yellow fever, smallpox, TAB, cholera and tetanus, Mr Dean failed to recognise the symptoms of malaria.

These were similar to a common cold or influenza and began nine days before he was admitted to hospital, where he almost died.

It was a dramatic finale to an epic journey which took Mr Dean only 14 days, but this was with a Land-Rover and not a 40ft trailer.

His main observations were that June, July and August are too hot and too wet for trucks, and sandstorms may develop after May. A heavily laden European-type 4x2 artic is, according to Mr Dean, unsuitable for the rough tracks and soft sand.

£15,000

However, comparing David Dean's assessments with those of Tom Bone, the results appear to be quite wide apart. For instance, in Mr Dean's opinion, £6,000 would be a fair rate for a 20ft container from Britain to Nigeria. Mr Bone managed the trip with five 40ft trailers with only £15,000 and hopes to be able to cut this down on future trips.

Naturally, anyone thinking of making the trip would be well advised to consult companies with experience of these routes, and to take all possible medical precautions.

For although there are known remedies for the common diseases, there is one African bug that has still left doctors bewildered. It is the mysterious Lassa Fever, a particularly nasty disease to which drivers may be unwittingly exposed.