Problems of the

Page 78

Page 79

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

HAULIER and

CARRIER

Diminishing the Scales of Charges for Parcels Carry ing. A Lucid Explanation of How They are Calcu lated. Pitfalls of an Ambitious Scheme

ARATE of 2d. per 28-lb. parcel per 54 miles, the figure at which I arrived in the previous article, is not likely to be of much use to hauliers. Those who read it without reference to the context, and without my explanation, may at once jump to the conclusion that I, too, have joined the price-cutting brigade. AS I explained, that rate is based on the assumption that the vehicle is loaded to capacity for the whole distance.

Now, it is the experience of those engaged in parcels traffic that an average of five minutes per call is involved, plus one minute per cwt. or per parcel for actual deliveries. The inquiry which is the basis of this article related to a double journey of 112 miles each way, once per day. If the average speed be assumed to be 28 m.p.h., then eight hours are needed for travelling, alone, without any allowance for time taken in collection and delivery.

Arising early in the morning in order to complete the work in good time is, unfortunately, no use whatever in this connection, because the haulier cannot start until his customers are ready for him to call for the parcels.

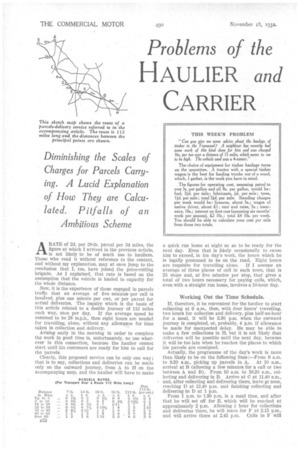

Clearly, this proposed service can be only one way ; that is to say, collections and deliveries can be made only on the outward journey, from A to H on the accompanying map, and the haulier will have to make a quick run home at night so as to be ready for the next day. Even that is likely occasionally to cause him to exceed, in his day's work, the hours which he is legally presumed to be on the road. Eight hours are requisite for travelling alone. If I assume an average of three places of call in each town, that is 25 stops and, at five minutes per stop, that gives a total of two hours necessary for paying calls, which, even with a straight run home, involves a 10-hour day.

Working Out the Time Schedule.

If, therefore, it be convenient for the haulier to start collecting at 9 a.m., then, with four hours' travelling, two hours for collection and delivery, plus half-an-hour for a meal, it will be 3.30 p.m. when the outward journey is completed, or, probably, 4 p.m. if allowance ho made for unexpected delay. He may be able to make a few collections in H, but it is not likely that deliveries will be possible until the next day, because it will ,be too late when he reaches the places to which his parcels are consigned.

Actually, the programme of the day's work is more than likely to be on the following lines :—From 9 a.m. to 9.20 a.m., picking up parcels in A. At 10 a.m., arrival at B (allowing a few minutes for a call or two between A and B). From 10 a.m. to 10.20 a.m., collecting and delivering in B. Arrive at C at 11.40 a.m., and, after collecting and delivering there, leave at noon, reaching D at 12.40 p.m. and finishing collecting and delivering In D at 1 p.m.

From 1 p.m. to 120 p.m. is a meal time, and after that lie will set off for E, which will be reached at approximately 2 p.m. Allowing I hour for collections and deliverie,s there, he will leave for F at 2.15 p.m., and will arrive there at 2.45 p.m. Calls in F will

probably take another 1, hour, bringing the time to 3 p.m., and the arrival at G will be at about 3.40 p.m. Leave G at 4 p.m., arrive at H at 4.30 p.m., and finish at about 5 p.m.

Even if he goes straight back to A, his day's work will not finish before 8.30 p.m., and, although that may occasionally be practicable, it is not fair regularly to expect it five days per week.

Loads Only One Way.

Clearly, therefore, it is possible to rely on loads only one way, which at once cuts the maximum total tounage down to an average, for the total distance out and home, of half the load capacity of the vehicle. Actually, as it is not to be expected that he will be • carrying a full load for even one way, but will average, at the most, only half full, it means that the overall average load will be a quarter of the capacity of the vehicle ; that is to say, about 10 cwt.

In the previous article 3-20d. per cwt. per mile was shown to be the basic rate, assuming the vehicle to carry full loads. I have shown that the average will be a quarter of that amount and, therefore, to make the minimum revenue specified, the basic rate must be increased fourfold to 12-20d. per cwt. per mile, which Is 0.6d. per cwt. per mile.

Now we come to the really intricate and difficult part of the calculation, namely, to assess the rates for small parcels and distances, less than the full length of the route and to show how and why those charges must he on a diminishing scale, falling both with increases in they distance and the weight of the parcel.

The rate of 0.6d. per cwt. per mile is based on the assumption that the vehicle runs straight through from end to end of the journey, making only one call and delivering the full load at that call. There is an allowance for only one call, say, five minutes, and 2025 minutes for the loading and unloading, making 4+ hours in all, including four hours for travelling time.

Each additional call involves an extra five or six minutes, and every division of the load involves, on that account, five or six more minutes, added to the total time of the journey, say 21 per cent. If each of the parcels averages 1 cwt., that would involve an addition of 10 calls, adding 10 times 21 per cent., or about 22 per cent., to the total time.

If the average weight of the parcels was 56 lb., there would be an addition of 20 to the number of calls, or an increase of approximately 44 per cent. to the time. If the average was 28 lb., the addition would be 40 calls and 88 per cent, to the number and percentage respectively, and so on.

The charge per parcel should be increased in accord ance with the foregoing percentages, so that a parcel weighing 1 cwt. must be charged 22 per cent. more than 0.6d., that is, 0.73d. A parcel weighing 56 lb. should be charged 0.53d., 28-lb parcels 0.28d., and smaller packages correspondingly.

As mentioned above, each stop involves an addition of 21 per cent. to the time of the journey. If, therefore, the average distance between stops were 40 miles, then, as the total journey is approaching 120 miles, there must be three stops, instead of one, which would be all that were necessary if every parcel went the whole distance.

For a package to be carried 40 miles involves, therefore, an addition of approximately 7 per cent. to the basic rates as just calculated. If the average distance between stops were 20 miles, that would involve six stops and the addition to the basic rate must be 14 per cent. Likewise for a delivery covering 10 miles, an 'addition of 30 per cent, would be necessary and, for five miles, 60 per cent.

Applying the foregoing reasoning and calculating rates for parcels to be delivered a distance of 20 miles, then, for a 1-cwt. parcel, we must take the basic rate of 0.73d. per mile, multiply by 20 for the distance, making 1s. 3d., and adding 15 per cent, for the mileage factor, making the rate is. 51d. for the 1-cw& package.

Similarly, for a 56-lb. parcel, the basic rate for which I have shown to be 0.43d. per mile, one should multiply by 20 for the mileage, making 81d., and add 15 per cent., bringing the rate up to 9id. A 28-lb. parcel can, in the same way, be shown to be chargeable at 6d., and a 14-lb. parcel at 41d.

Rates for Parcels Transport.

To all these, rates must still be added the agency commission of 10 per cent per parcel, which brings the foregoing 20-mile rates up to 1s. 7c1. for the 1-cwt. parcel, 11d. per 56-lb. parcel, 7d. for 28 lb. and 54d. for 14 lb. ' In the table which appears on the previous page, all these factors are quoted for a series of mileages and for parcels of various weights.

Two points are still left for consideration. First, it would be impossible to deliver a full load of 7-lb. parcels in a day, assuming that they were for a variety of destinations, or even a full load of 14-lb. packages. As, however, that is a contingency which is hardly likely to arise, it needs no lengthy discussion.

Then there is the difficulty of light, bulky parcels. This is bound to arise, because these are the consignments which senders like to foist on the motor haulier. Such parcels must be charged at from 50 per cent. to 100 per cent. extra, according to circumstances.