11111EN TIVO-SIlitiht 11

Page 16

Page 17

Page 18

Page 19

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

IS ECONOMY RECORDS

Paden Eight-whei Fine Performance Torque and Other istics of Two-strc Permit Standard be Used Without

WHEN the Foden two-stroke oil engine was announced last year, al fuel consumption equal to 250 ton-m.p.g. was claimed for its road performance. Critics of the two-stroke engine scorned the idea that this power unit could possibly equal a fourstroke for economy, but a test of a Foden eight-wheeler fitted with the two-stroke unit satisfied me that the manufacturer's claim was on the modest side.

Although the critics may have based their forecasts of high fuel consumption on the results of bench 'tests, the extreme liveliness and smooth torque of the Foden engine are the vital factors which account for the power and economy obtained on the road.

The characteristics of the FD.6 engine are impressive, comparing favourably with those of existing four-stroke units of equal power output. Of 4.09-litre capacity, it has an out put of 126 b.h.p. at 2,000 and 350 lb.-ft. torque at 1,500 r.p.m.

Structurally, the engine is robust, the crankcase and cylinder block form a single-piece aluminium-alloy casting, with push-fit wet liners, which are registered by a flange in a recess at the top of the block. The casting is divided horizontally into three main compartments—the water jacket (at the top), the air chest and the crank chamber. Rubber rings are inserted in grooves in the liners to seal the joints between the chambers.

The main-bearing bolts are extended through the casting to secure the two nickeliron head castings, each covering three bores. There are two exhaust valves to each cylinder, and their cast-iron guides are in direct contact with the cooling water. The rocker gear, valves, push rods and injectors form an integral assembly with the head, and are removed as a unit.'

Replacing the conventional head gasket, a joint ring is fitted to the top of each liner, whilst the water holes and tappet-guide holes are sealed by rubber grommets. The seven-bearing unhardened nickel-steel crankshaft, B8 of robust proportions, has large-diameter and equalwidth bearing journals. All bearings are of steel-shell pattern, with white-metal linings. The connecting rods are split diagonally at the big-ends, and the caps are secured by two bolts, being located in position by a step joint on one side only.

Tin-plated cast-iron pistons are employed, each having five rings. A wide composite fire ring covers the top land, whilst two wedge-shaped compression rings are fitted immediately below the top land. An air-chest sealing ring, fitted below the gudgeon pin, prevents scavenge air from leaking through to the crankcase chamber when the piston is at the top of its travel. An oil scraper ring at the bottom of the piston controls

(7) The term " potted power" might be well applied to the Foden engine, its compact construction permitting additional space in the cab. A transverse drive from the front of the crankshaft operates the engine water pump and hydraulic pump for the brake system.

the supplY of lubricating oil. With the breathing system of the two-stroke engine, the consumption of oil may remain• constant throughout the life of the unit. The Foden oil-control ring is set so that one gallon of oil is used to every 1,500 miles run.

Helical gearing is used for the timing arrangements, which are located at the rear of the unit_ All the components are operated through single drives. A skew gear at the front •of the crankshaft drives a transverse shaft operating the water pump and the gear pump for the Foden hydraulic braking system.

Geared to turn at twice engine speed, the Rootspattern blower, made by the vehicle manufacturer, incorporates two-lobe rotors. Air is drawn through a specially designed filter and silencer, and is delivered direct to the air chest. The C.A.V. H-type hydraulically governed fuel-injection pump, bolted to the top of the blower casing, supplies fuel to the single-hole injectors, which are inclined in the head at an angle of about 45 degrees and spray tangentially into the combustion space. The combustion chamber is formed by a toroidal cavity in the piston crown, and the requisite turbulence is obtained by tangential ports, formed in the base of the liners, in conjunction with deflectors in the air chest.

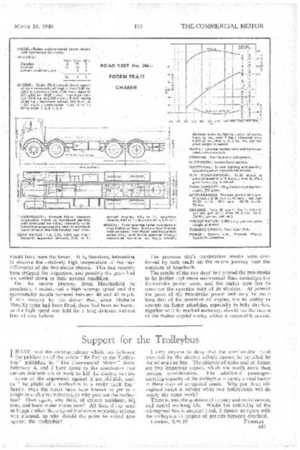

Because of the smooth torque, and absence of high stresses, the two-stroke engine can be fitted into the standard Foden chassis without the need for increasing the size of the transmission units. The model provided for my test was the F.E.6/15, which is the rigid eight-wheeler, with a permissible gross weight of 22 tons. Because of the lightness of the power unit, this model has an additional 3 cwt. of payload capacity.

The chassis has a five-speed gearbox incorporating an extra-low ratio, a twin-drive rear bogie, and the Foden hydraulic two-leading-shoe braking system, which takes effect on the first, third and fourth axles. With the exception of the power unit, this model is similar to the F.G. chassis, which was described in "The Commercial Motor" road-test report No. 346 (June 25, 1948).

Before starting the test, I watched the performance of one of the Foden engines on the bench, and noted the remarkable snap acceleration and deceleration of the unit. No-load acceleration per second was at the rate of approximately 4,000 r.p.m. The normal "Diesel knock" of the four-stroke engine was absent, but in its place there was a more pleasant mixture of gear whine and roar from the induction and exhaust. Apart from the lower level of noise in the cab, the note of a two-stroke is less tiring than the crackle of the fourstroke, and made my two-day test even more enjoyable than it might otherwise have been.

It took comparatively little time for the engine to warm up to full performance, and after leaving the outskirts of Sandbach, we were riding along in top gear B9

at a steady 35 m.p.h. At this speed the engine assumed a pleasant hum, which was made up of gear, air, exhaust and injector noise, of approximately the same level as that of a quiet four-stroke power unit. When speed was increased to 43 m.p.h. (2,150 r.p.m. engine speed), there was slightly more injection and exhaust noise.

Up 1 in 6 from Standing Start

It did not take long to reach Astley Hill, near Congleton Station, and a halt was made at the foot to time the test to the Coach and Horses Inn, which is near the end of the climb. Low gear was engaged to start on the 1-in-15 incline, and a rapid change to super-low ratio was required on reaching the 1-in-6 section. Climbing at maximum engine revolutions, the road speed was approximately 4 m.p.h., but when the Tapley meter recorded a rise of 1 in 10, the driver re-engaged low gear. Without the additional engine revolutions at the top end of the range—that is, from 1,800 r.p.m. upwards —the test would have had to have been made with superlow gear engaged for the whole distance. The result was that the Foden completed the climb in 5 mins. 6 secs., or precisely 3 mins. less than any four-strokeengined chassis of a similar class tested on this hill.

There was a boost pressure of 4.5 lb. per sq. in. in the air chest when the engine was turning at 2,150 r.p.m., the governed speed. When descending the hill, with the throttle closed, the air pressure rose to 6 lb. per sq. in., a feature which shows adequate scavenging. There was no visible exhaust at any time.

A main-road hill between Sandbach and Newcastleunder-Lyme was climbed in competition with a large four-stroke-engined vehicle of another make. The Foden completed the climb in 71 mins. and there was an interval of 24, mins. before the other vehicle came on the scene.

Exceptional Liveliness -.

Although rather high geared to obtain the best results in acceleration, the two-stroke chassis revealed outstanding liveliness, 20 m.p.h. being reached from a standing start through the gears in 17.4 sees. and 30 m.p.h. in 43 secs. The high governed speed of the power unit helped to produce these fine results and gear changes from second to third ratios were made at 16 m.p.h. and to direct drive at 25 m.p.h.

Top-gear performance was within the limits demanded by modern standards, but better results would have been obtained with a lower axle ratio. In direct drive it took 39.6 secs, to reach 20 m.p.h. from a rolling start of 10 m.p.h., and 70 secs, to reach 30 m.p.h. with the lively. "top-end" performance of the engine; no driver on normal service would attempt to engage top gear under 20 m.p.h.

Braking tests made last year with the Foden FG. chassis were marred by a soft road surface, and the results did not do full justice to the efficiency of the system. I checked the earlier results with those of the FE, chassis and recorded stopping distances of 23i ft. from 20 m.p.h. and 46 ft. from 30 m.p.h. After 2,000 miles the brakes had bedded down to a nicety, but an operator purchasing a new vehicle with Duron P.20 facings must not expect such a high degree of braking in the first few hundred miles. I have found that these facings wear comparatively, little and retain their elliCiency without fading up to great temperatures.

Fuel-consumption trials were conducted with a precise calculation of the quantity used. Because of the fuel-return system on the FE. chassis, my small test tank could not be employed. Instead, the main tank was turned until the filler neck projected almost vertically, and vent pipes were arranged to prevent air BIO

locks. The tank was filled before starting the trials and the temperature of the fuel recorded. The quantity required to replenish the tank at the end of the course was weighed to the nearest f oz. and an adjustment made for the variation of temperature I followed the route covered during my previous tests, which starts from Sandbach and passes through the congested town of Middlewich and on to Holmes Chapel. A short detour at Holmes Chapel brought us back on the original course, which has a total length of 17 miles. During the first run the traffic in Middlewich caused a serious delay and halts at traffic lights and corners were not conducive to an economical result. Nevertheless, a consumption equivalent of 10.6 m.p.g. was returned, and the second trial, made under more normal conditions, showed an improvement of 0.91 m.p.g. This reSult of 11.51 m.p.g. has been used as the basis for my calculations extended to gross ton-m.p.g.

Three Tests of Fuel Consumption

Critics of the two-stroke would say this result couid not be repeated, so I made a third test during the early evening, when the run was reasonably straightforward, and only four stops were required in the 17 miles. Intermediate ratios were engaged on the inclines in Middlewich, and when starting from rest and negotiating 'corners in Sandbach and Holmes Chapel. An average speed of 25.9 m.p.h. was maintained and the consumption rate was calculated as 12.05 m.p.g. The results of the second and third trials, showing over 250 ton-m.p.g., constitute a record in economy for any vehicle tested by "The Commercial Motor."

On the second day an assault was made on Dumbers Hill, between Congleton and Buxton, on the fringe of the Pennines. I -found that, with the instantaneous reaction of the power unit to the accelerator pedal and the gear arrangements of *the Foden box, changes in ratio could be made extremely quickly. The gearbox has constant-mesh gearing with fine-pitch dog engagement. I controlled gear selection with the aid of the engine tachometer and engaged lower ratios at

1,500 r.p.m. and higher gears at 2,100 r.p.m. This timing gave a remarkably lively performance.

Better Performance on Hills Temperatures were taken at the foot of Dumbers Hill, a It-mile climb of I in 16 average gradient Engine oil registered 134 degrees F. and the water in the radiator top tank 148 degrees F. Several sharp inclines were recorded by the Tapley meter during the climb, the maximum .reading being 1 in 6i. Long periods were spent in low and super-low ratios, but even greater use of the tow gears had to be made by a similarly laden Foden FG. eight-wheeler, which was following the two-stroke to give comparative transmission temperatures.

It took 15 minutes for the Foden-engined vehicle to reach the summit of the hill, and during that time airintake and air-chest temperatures reached maximum readings of 108 and 128 degrees F. respectively. Gearbox, ambient and axle temperatures had been taken by the time the standard chassis arrived, some 41 Minutes later.

The two-stroke temperatures in degrees F. at the summit were: Top tank, 154; engine oil, 164; gearbox, 122; front differential, 118, and rear differential, 145. The standard Foden FG. chassis temperatures were: Gearbox, 102; front differential 98, and rear differential 110. With a following wind of approximately 15 m.p.h. and an ambient of 50 degrees F., it was reasonable to assume the rear-differential temperatures' would have been the lower. It is, therefore, interesting to observe the relatively high temperature of the rear differential of the two-stroke chassis. This had recently been stripped for inspection, and possibly the gears had not settled down to their normal condition.

On the return jOurney, from Macclesfield to Sandbach, I maintained a high average speed and the speedometer needle hovered between 40 and 43 m.p.h. I was assured by the driver that, since Michelin Metallic tyres had been fitted, there had been no bursts, so the high speed was held for a long distance without fear of tyre failure. The previous day's acceleration results were confirmed by tests made on the return journey near the outskirts of Sandbach.

The results of the two days' test proved the two-stroke to be livelier and more economical than contemporary four-stroke power units, and the maker now, has to convince the operator only of its stamina. At present the price of the two-stroke power unit may be mo:e than that of the standard oil engine, but its ability to operate on faster schedules, especially in hilly districts, together with its marked economy, should see the return of the higher capital outlay within a reasonable period.