Electric v diesel

Page 39

Page 40

Page 41

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

OPERATORS are constantly being told how much cheaper it is to run an electrically powered vehicle than it is to run one using the internal combustion engine. The question is — how true is such a claim?

Comparing like with like is one thing — comparing an electric (vehicle) to a diesel engined vehicle is something else entirely.

But, try to do this we must, if we are to make any sense of the relative costings for both types of transport.

Among the immediate problems that arise with such a comparison are those of establishing vehicle compatibility and having an awareness of the discrepancy in capability For instance, the electric has a restricted range — perhaps something over 50 miles — while the diesel or petrol equivalent, if such a thing exists, has no such restriction. Therefore, while an electric may be used, for example, on one delivery round a day, the diesel or petrol vehicle can do two.

Greater mileage and use will reduce the cost per mile and produce more economical usage.

The comparison is further inhibited by the fact that electrics are used, almost exclusively, by the dairy trade, which is not directly comparable with a conventional urban distribution operation.

Nevertheless, there are dairymen who have operated both, and their experience might well prove useful when considering the relative costings.

Manufacturers of electrics claim they are much cheaper to run, and that if the operator is not restricted by the comparatively short distance they run before the batteries have to be recharged, electrics are the more economical proposition.

This claim is based mainly on two factors. Firstly, that electric vehicles have a much longer life (15 years as against five for diesel or petrol) and that fuel is much cheaper.

There are other considerations such as the cheaper road fund licence, cheaper insurance and exemption from plating and testing On the longer life of the vehicles, however, electrics users have pointed out that the matter is not as simple as has been represented.

They say that after about seven years, it is necessary. almost to rebuild the vehicle completely, though the original chassis skeleton, more robustly built than the combustion engined vehicle, does last 15 years.

Fuel is another bone of contention. It depends on what part of the country an operator works in, and therefore which regional electricity board is supplying the electricity, as to how much the fuel costs.

If an operator is unlucky enough to have premises situated in an area where the regional electricity board has a restricted cheap supply period — often not available at the time of greatest charge --' then fuel costs will be higher than elsewhere.

In the main, fuel for the electric does cost considerably less than for a diesel or petrol vehicle.

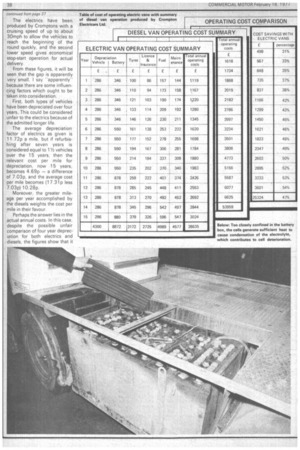

With all this in mind, it is worth examining costing figures produced, first, by the electric vehicle manufacturers, and then by an operator under actual operating conditions. Though Crompton Electricars point out that the figures shown on page 38 for diesel van operation are produced on a similar basis to those for the electric, they do not provide actual details.

Nevertheless, figures for the total operating costs can be compared. Vehicle mileage has been taken as 40 miles a day for a 248 week year, about 10,000 miles a year.

The vehicle prices are those which prevailed in August 1975, and maintenance costs are based on information from a number of sources, including CM Tables of Operating Costs.

However, for depreciation purposes, a vehicle life of 15 years without further rebuilding has been allocated to electric vehicles, and replacement after five years for the diesel vehicle.

The battery charger has been included in the depreciation for electric vehicles with a life of 15 years also.

The overall result at the end of the period is an average cost per mile of 19p for the electric and 35p a mile for the diesel I feel this is too great a gap, but to analyse the figures properly, one would have to have the costing details for the diesel van. But comparative costs of running electrics, diesels and petrol vehicles, produced by Smith's Electric Vehicles, shows a somewhat narrower cost gap.

These figures have been accepted by the Electric Vehicle Association, and will figure in a brochure which the Association is preparing.

Smith's agrees that it might have pitched factors a bit on the high side, but points out that this has been done on both sides of the equation, and therefore, there is a compensating effect for all three types of vehicle.

Despite this, the figures include the cost of two-star petrol at 80p a gallon, and diesel at 80p a gallon also. The petrol vehicle (a Ford Transit 115) has been credited with a fuel consumption of only 12mpg and the diesel version of the same vehicle with 17mpg.

Both these are rather low and would be more realistic at 20 and 25mpg on a stop-start delivery run. In fairness, it must be said that the cost of electricity at 3p a unit is also high.

Dividing the standing cost . per week into the standing cost per year, one can see that Smith's have also decided the vehicles can be run for 52 weeks a year.

By a similar calculation, using the total operating costs per week and the cost per mile, it can be determined that the basis of the weekly mileage considered is 150, or only about 8,000 miles a year. Total under-utilisation for a combustion-engined vehicle.

The maintenance cost per mile for diesel and petrol vehicles is rather high, too, at 15.4p and 14,1p .a mile for petrol and diesel respectively.

When adjustments have been made to take all this into consideration, the gap in the comparative operating costs per mile narrows appreciably to about 21p, 28p and 26p respectively.

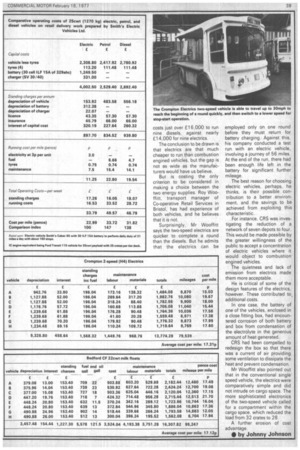

I was able to obtain details of actual costing for 1 976 for both electric and diesel doing a similar job for one operator.

The vehicles concerned were N and M registered Bedford CF 22cwt milk floats, and Crompton two-speed electrics, The electrics have been produced by Cromptons with a cruising speed of up to about 30mph to allow the vehicles to reach the beginning of the round quickly, and the second lower speed gives economical stop-start operation for actual delivery.

From these figuree, it will be seen that the gap is apparently very small. I say 'apparently' becausethere are some influencing factors which ought to be taken into consideration.

First, both types of vehicles have been depreciated over four years. This could be considered unfair to the electrics because of the admitted longer life.

The average depreciation factor of electrics as given is 11.72p a mile, but if refurbishing after seven years is considered equal to 11/2 vehicles over the 15 years, then the relevant cost per mile for depreciation, now 15 years, becomes 4.69p — a difference of 7.03p, and the average cost per mile becomes (17.31p less 7,03p) 10.28p.

Moreover, the greater mileage per year accomplished by the diesels weights the cost per mile in their favour.

Perhaps the answer lies in the actual annual costs. In this case, despite the possible unfair comparison of four year depreciation for both electrics and diesels, the figures show that it costs just over £.16,000 to run nine diesels, against nearly £14,000 for nine electrics.

The conclusion to be drawn is that electrics are that much cheaper to run than combustion engined vehicles, but the gap is not as wide as the manufac. turers would have us believe.

But is costing the only criterion to be considered in making a choice between the two energy supplies. Roy Wooffitt, transport manager of Co-operative Retail Services in Bristol, has had experience of both vehicles, and he believes that it is not.

Surprisingly, Mr Wooffitt says the two-speed electrics are quicker to complete a round than the diesels. But he admits that the electrics can be employed only on one round before they must return for battery charging. Against this, his company conducted a test run with an electric vehicle, involving a journey of 56 miles. At the end of the run, there had been enough life left in the battery for significant further mileage.

The best reason for choosing electric vehicles, perhaps, he thinks, is their possible contribution to a better environment, and the savings to be achieved from exploiting this characteristic.

For instance, CRS was investigating the reduction of a network of seven depots to four. This would be made possible by the greater willingness of the public to accept a concentration of electric vehicles where it would object to combustion engined vehicles.

The quietness and lack of emission from electrics made them more acceptable.

He is critical of some of the design features of the electrics, however. These contributed to, additional costs.

In one case, the battery of one of the vehicles, enclosed in a close fitting box, had encountered corrosion of both battery and box from condensation of the electrolyte in the generous amount of heat generated.

CRS had been compelled to redesign the box so that there was a current of air providing some ventilation to dissipate the heat and prevent condensation.

Mr Wooffitt also pointed out that in the conventional single speed vehicle, the electrics were comparatively simple and did not intrude on cargo space. The more sophisticated electronics of the two-speed vehicle called for a compartment within the cargo space, which reduced the load from 32 crates to 28.

A further erosion of cost advantage.

• by Johnny Johnson