THE DRINKING MAN'S FLEET

Page 67

Page 68

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

Tolly Cobbold is a medium-sized regional brewery with big ideas. How does the company's group fleet engineer, Tony Artiss, view the modem brewery transport scene?

• During the four years in which Tolly Cobbold has been running two Scania G82 drawbar units, it has suffered only three breakdowns. The Ipswich-based brewery has, since 1983, used the two drawbars on a daily trunking run to Brentwood in Essex, where their Ray Smith demountable bodies are swopped around to take out new deliveries to the Greater London area and to return the empties.

"When we looked at the operation, we decided to buy a premium vehicle," says Tony Artiss, Tony Cobbold's group fleet engineer. "From deciding to go to a drawbar operation, to getting the vehicles on the road took 17 months." Artiss was particular about buying Scanias and about what went into the rigs.

"The prime movers are both 16-tonners but the units run at 32-tonnes gross train weight. They have got 172kW Scania engines, 10-speed Scania splitter boxes and air suspensions."

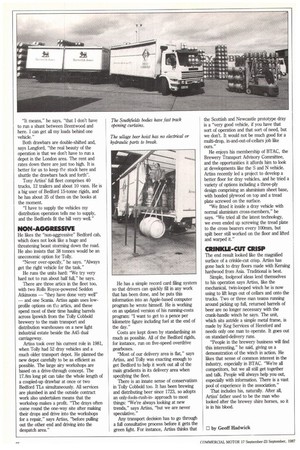

Ray Smith Demountables told Tolly Cobbold it usually fitted conventional suspension systems, but Artiss went his own way. "It had to be air suspension on the drawbars," he says, "first because air suspension gives a better ride for the product, second because it helps us to demount the boxes, and third, because it means we can lower the rear platform 100mm to 125mm to help unloading."

He has been pleased with the results. The Neway air suspension on the trailers has been reliable and it has obviously kept barrel movement to a minimum. The interior of the four-year-old drawbar bodies is excellent.

Why did he choose Scania?

"The low-step G cab was just what we needed, and I liked the way in which Scania could offer us air suspension built and engineered in from the start." Add-on air suspension systems put him off other marques such as Ford or Bedford.

Southfields of Loughborough put the drawbar bodies together on the Ray Smith demount frames, and both units are capable of going out from Ipswich as three separate loads through an intriguing design which allows the front bulkhead of one compartment to open inwards and let the loading men walk through to the next compartment. `Folly Cobbold has two 3.7m drawbar compartment bodies, one 7.4m compartment and one 6.7m compartment.

Once the front bulkhead inner swing doors are opened, access forward is achieved by lifting the roller shutter door at the back of the next compartment.

SERVICING LONDON

Tolly's transport manager, Bryan Langford, has three men running the two daily drawbar shuttles to Brentwood. When the units arrive and split up at Brentwood, says Langford, the single-man unit takes the "easy stuff, the wine bar and restaurant run. The double-man unit services our free trade outlets in London, including six tied pubs we now have in the London area".

Tolly is expanding at present, geographically and in terms of the products it sells. Langford says the drawbar unit is fine for current operations, but it could be too small if things continue to boom.

Langford likes being able to divide the units into three and still allow enough to double-load around London.

"It means," he says, "that I don't have to run a shunt between Brentwood and here. I can get all my loads behind one vehicle."

Both drawbars are double-shifted and, says Langford, "the real beauty of the operation is that we don't have to run a depot in the London area. The rent and rates down there are just too high. It is better for us to keep tke stock here and shuttle the drawbars back and forth".

Tony Artiss' full fleet comprises 40 trucks, 12 trailers and about 10 vans. He is a big user of Bedford 15-tonne rigids, and he has about 35 of them on the books at the moment.

"I have to supply the vehicles my distribution operation tells me to supply, and the Bedfords fit the bill very well."

NON-AGGRESSIVE

He likes the "non-aggressive" Bedford cab, which does not look like a huge and threatening beast storming down the road. He also insists that 38 tonnes would be an uneconomic option for lolly.

"Never over-specify," he says. "Always get the right vehicle for the task."

He runs the units hard: `We try very hard not to run about half full," he says.

There are three artics in the fleet too, with two Rolls Royce-powered Seddon Atkinsons — "they have done very well" — and one Scania. Artiss again uses lowprofile options on t112 artics, and these spend most of their time hauling barrels across Ipswich from the lolly Cobbold brewery to the main transport and distribution warehouses on a new light industrial estate beside the A45 dual carriageway.

Artiss took over his current role in 1981, when Tolly had 52 dray vehicles and a much older transport depot_ He planned the new depot carefully to be as efficient as possible. The large airy workshops are based on a drive-through concept. The 17.8m long pit can take the whole length of a coupled-up drawbar at once or two Bedford Its simultaneously. All services are plumbed in and the outside contract work also undertaken means that the workshop makes a profit. "The drays often come round the one-way site after making their drops and drive into the workshops for a repair," says Artiss, "before pulling out the other end and driving into the despatch area." He has a simple record card filing system so that drivers can quickly fill in any work that has been done, and he puts this information into an Apple-based computer program he wrote himself. He is working on an updated version of his running-costs program: "I want to get to a pence per kilometre figure including fuel at the end of the day."

Costs are kept down by standardising as much as possible. All of the Bedford rigids, for instance, run on five-speed overdrive gearboxes.

"Most of our delivery area is flat," says Artiss, and Toffy was exacting enough to get Bedford to help it work out all of the main gradients in its delivery area when specifying the fleet.

There is an innate sense of conservatism in Tony Cobbold too. It has been brewing and distributing beer since 1723, so adopts an only-fools-rush-inapproach to most things: "We're always looking at new trends," says Miss, "but we are never speculative."

Any transport decision has to go through a full consultative process before it gets the green light. For instance, Artiss thinks that the Scottish and Newcastle prototype dray is a "very good vehicle, if you have that sort of operation and that sort of need, but we don't. It would not be much good for a multi-drop, in-and-out-of-cellars job like ours."

He enjoys his membership of BTAC, the Brewery Transport Advisory Committee, and the opportunities it affords him to look at developments like the S and N vehicle. Artiss recently led a project to develop a better floor for dray vehicles, and he tried a variety of options including a three-ply design comprising an aluminium sheet base, with bonded plywood on top and a tread plate screwed on the surface.

"We fitted it inside a dray vehicle with normal aluminium cross-members," he says. "We tried all the latest technology, we even ended up screwing the tread plate to the cross bearers every 100mm, but spilt beer still worked on the floor and lifted and warped it."

CRINKLE-CUT CRISP

The end result looked like the magnified surface of a crinkle-cut crisp. Artiss has gone back to dray floors made with Keruing hardwood from Asia. Traditional is best.

Simple, foolproof ideas lend themselves to his operation says Artiss, Ifice the mechanical, twin-looped winch he is now using to lift kegs out of cellars and onto the trucks. Two or three man teams running around picking up full, returned barrels of beer are no longer necessary with the crank-handle winch he says. The unit, which sits astride a simple metal frame, is made by Keg Services of Hereford and needs only one man to operate. It goes out on standard-delivery runs.

"People in the brewery business will find this interesting," he said, giving us a demonstration of the winch in action. He likes that sense of common interest in the industry, especially in BTAC. "We're all competitors, but we all still get together and talk. People will always help you out, especially with information. There is a vast pool of experience in the association."

That inckides his, naturally. After all, Artiss' father used to be the man who looked after the brewey shire horses, so it is in his blood.

0 by Geoff Hadwick