Depreciation Causes Disagreement on Coach Charges

Page 45

Page 46

Page 49

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

How Two Different Methods of Assessing Depreciation-by Time and by Mileage-Affect Minimum Remunerative Rates and Give Rise to Eternal Controversy

OF all the business aphorisms that have from time to time come to my notice, there is one in particular which recurs. I first heard it many years ago, when one of the foremost oil magnates of the time, replying to a charge that petrol prices were too high, said, "The price of a commodity is what it will fetch." His justification for that statement was the eternal and immutable law of supply and demand. Perhaps one reason why that remark comes often to my mind is that it is so apt in its application to goods and passenger transport.

My business in these articles for the past 25 years has not been, as so many people seem to think, that of dictating Tales for charges, but rather to indicate minima below which the operator should not go if he expects to make a reasonable profit, if, in any case, the charge be more than that minimum, I obviously can have nothing to say, except that I do not think it right or even businesslike to charge rates or fares which are excessive.

My figures are often criticized. Sometimes I am told that my costs are too high, sometimes that they are too Iowa circumstance which confirms my belief that I am not far wrong, as I always insist that the data which I give are based on averages and may not, therefore, apply strictly to individual cases.

• Perhaps one of the kindest compliments which has ever been paid me in this connection was that at Leicester the other week, when a man whom I had not previously met greeted me by saying, "Oh, yes, you are the man who prepares the figures and, when we first see them, we say they are all wrong, but it isn't very long before we are saying 'how right you are.'" In those happy pre-war days when, under the combined xgis of " The Commercial Motor," Associated Road Operators and the Commercial Motor Users' Association, I used to tour the country, lecturing on costs and charges. I had more often to meet with these criticisms. There was one in particular that invariably arose when I touched upon the subject of coach fares, costs and charges for hire, It was that my assessment of depreciation was insufficient.

That happened in the early days of my lectures and, in consequence of those. criticisms, I took steps to verily my figures. The cause was the vast difference, as between one operator and another, in.the period for .which vehicles were run before being sold. Some operators bought new vehicles and disposed of them quickly. Others purchased new vehicles, using them first for private hire and later as buses or express carriages. There were also operators who invariably bought used vehicles.

In this field it is not so much a question of supply and demand, as of suiting the coat to the cloth. The coach operator who caters for a high-class clientele in a district in which his customers are able to pick and choose requires up-to-date vehicles, and if he has no further use for them when they have become unsuitable for private hire or excursions and tours, his depreciation factor is inevitably high. It was the difference between that operator's depreciation rate and those of other types of user which gave rise to the controversies into which I so often found myself bound to enter.

In an article entitled "Why fown and Country Coach Rates Differ" (" The Commercial Motor," August 29), two or three paragraphs were devoted to this question of depreciation of coaches I thought when I wrote the article that I should be lucky if I escaped scot-free. I was nearly lucky, but not quite. I have had one plaintive letter from a reader

who-wants to know what I mean by stating in one and the same article that the depreciation Of a coach should be IS. per mile, 2!7,d. per mile, and 30. per mile.

I thought I had made the matter perfectly clear, In that article I accepted the fact that many operators like ti depreciate on a time basis, and' I pointed out the disadvantage of that method, namely, that in the case of a winter job involving a short mileage, depreciation would approximate to Is. a mile, whereas in the summer, when mileages covered were large, depreciation would be no more

than 20. per mile. In other words, in the winter, when work was scarce, a high rate would be required and, in summer, when it was plentiful, a low rate would be profitable. I then showed that if an operator depreciated on a mileage basis, • the figure would be 30. per mile, which is not extreme, no matter what may be the mileage per trip or per day. '

This week I propose to approach the subject from an entirely different direction. I am going to deal with operating costs of a 32-seater coach as a whole, but will estimate them in two different ways.

In the first instance I shall use " The Commercial Motor" method, which is, in effect, the way in which costs are averaged in" The Commercial Motor" Tables of Operating Costs. Secondly, I shall employ an alternative method.

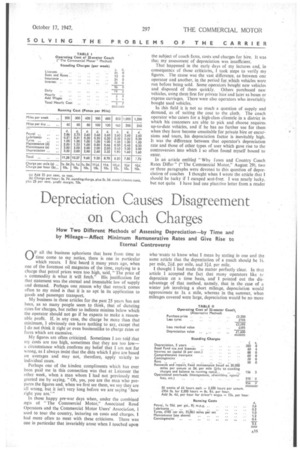

Difference in Approach 1 have set out the figures in Tables I and II. The principal difference is that whereas in "The' Commercial Motor" method, depreciation is calculated on a mileage basis, as I still think is preferable, in the alternative method it is a standing charge. The reader --tho is familiar with "The Commercial Motor" Tables of Operating Costs will at once spot that there is no provision for wages in the standing charges. I have omitted that item because, in connection with the assessment of charges for coach hire, I find it better to assess wages on an hourly basis. I have made the same modification in the alternative method.

The basic calculation for depreciation is the same in both methods and it appears at the top of Table IL The purchase price of the vehicle is taken to be £2,200 and from that figure is deducted the cost of a set of tyres, leaving the vehicle, less tyres, at £2,095. Tyres wear out much more quickly than the coach and the depreciation of tyres is assessed separately. The next thing to do is to assume a price which the operator will get for his vehicle when he sells it at the end of a pre-determined period of use. In this case five years has been taken and it is assumed that he will obtain £495. To-day he might get £2,000 for the coach. Five years hence the price will depend on the market, and in my view £495 is a reasonable expectation. Deducting £495 from the £2,095 we get £1,600, which is what is called the depreciation value. According to the 'alternative method, that figure of 11,600 is divided by five and the annual figure for depreciation is £320. . • " The Commercial Motor ".method takes into account the possibility that with a low annual mileage, a vehicle may be kept in use for a longer period, and 240,000 miles is regarded as its life." Dividing £1,600 by 240,000 gives 1.60d. per mile. That is .what I call the basic figure for depreciation per mile, but it applies only if the vehicle does at least 48,000 miles per annum, the equivalent of a five year life. If the coach does not run so many miles per annum, the depreciation figure per mile must increase, ctherwise we should have to depreciate over a tremendous period.

If, for example, it ran only 10,000 miles per annum, the depreciation would be over 24 years, which is absurd, and I correct the depreciation figure in this way: for every 2,000 miles fewer than 48,000 per annum I add 5 per cent. to the 1.60d. basic figure for depreciation per mile. Thus, referring to Table'!, if a vehicle does an average of only 400 miles per week (20000 miles per annum), it runs 28,000 miles fewer than the basic figure of 48,000. As I allow 5 per cent. for every 2,000 miles I must add 70 per cent, to the 1.60d. to arrive at the appropriate amount for depreciation per mile with a vehicle running only 400 miles per week. Seventy per cent, added to I.60d. equals 2.80d., and that is the figure which appears in the appropriate column in Table L

Allowance for Obsolescence

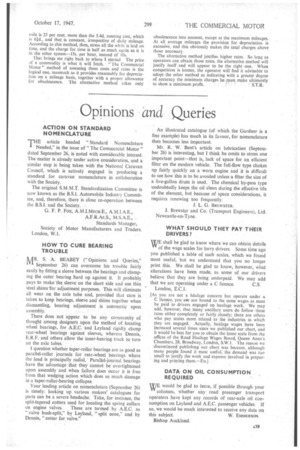

There is thus an allowance of the difference between 2.80d. and 1.60d., namely I.20d., for obsolescence, which is required because, although the vehicle is not wearing out so quickly, it is becoming less valuable. The qualification of this point of view appears in Table IV.

Another way of looking at the matter is this-the figures can again be found in Table IV. A vehicle running 50,000 miles per annum is given a life of 250,000 miles, a fair approximation to the 240,000 miles which I have already named as being correct. If the vehicle runs only half that mileage per annum, 25,000, its life before it is written off is 165,000 miles. The difference of 75,000 miles is written off because of obsolescence.

Now let us consider this item in relation to the alternative method, in which the vehicle is depreciated at the rate of £320 per annum regardless of mileage (Table IV). By that system a vehicle is written off when it has covered no more than 50,000 miles, if it runs an average of 10,000 miles per annum. Even if it runs 20,000 miles per annum, which is a good average figure for a country operator, it is written off at 100,000 miles, which is much too low for a vehicle that cost £2,200. That is another reason, apart from the one given in the article of August 29, why I think depredation should be reckoned by mileage.

Operators who are considering the question of rates may view this matter from quite a different direction. Referring to Table III it will be seen that the appropriate minimum charge is higher when depreciation is taken as a standing charge than it is by "The Commercial Motor" method, wherein depreciation is regarded as a running cost. The rate is much higher when the vehicle is running a small mileage: for a 40-mile day the difference is El 2s. 6d. a day, being £7 10s., according to "The Commercial Motor" method, and LS 12s. 6d. by the alternative method. The difference gradually diminishes until, at 200 miles per day (or about 48,000 miles per annum), the charges are the same.

The reason for this difference can be appreciated if reference again be made to Tables I and II. In Table I I show at the bottom the time and mileage charges to be made for a 32-seater coach, according to "The Commercial Motor" method, for various weekly mileages. The time charge. is 1Gs. per hour, whereas the mileage charge is greatest for a low daily mileage, being Is. 3d. per mile, falling to 91(1., per mile at the maximum mileage of 240 per day. By the alternative method the charge per hour should be the cost, which is I2s. per hour, as shown in Table II, plus 25 per cent. profit margin, which is 15s. The charge per

mile is 25 per cent, more than the 5.4d. running cost, which is 61d., and that is constant, irrespective of daily mileage. According to this method, then, stress all the while is laid on time, and the charge for time is half as much again as it is in the other system-15s. per hour, instead of 10s.

That brings me right back to where I started The price of a commodity is what it will fetch. "The he Commercial Motor" method of assessing these costs and rates is the logical one, inasmuch as it provides reasonably for depreciation on a mileage basis, together with a proper allowance for obsolescence. The alternative method takes only

obsolescence into account, except at the maximum mileages. At all average mileages the provision for depreciation is excessive, and this obviously makes the total charges above those necessary.

The alternative method justifies higher rates. So long as operators can obtain those rates, the alternative method will justify itself and will appear to be the right one. When competition is keener, the operator will find it advisable to adopt the other method as indicating with a greater degree of accuracy the minimum charges he,ranst, make ultimately to show a minimum profit. S.T.R.