WHAT PRICE GLASNOST?

Page 41

Page 42

Page 43

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

• Four-wheel-drive off-road vehicles have been one of the niche-marketing successes of the 1980s. Success, however, is ususally followed by a strong push up-market as manufacturers vie with each other to provide better specified and, of course, more expensive models. Combined with a move away from utility vehicles to leisure or recreational models, this has left buyers of traditional 4x4 workhorses with a comparatively limited choice.

Even the Japanese, who bulk their reputation on cheap, basic motors for the masses, have largely moved on to more lucrative things. As our comparison chart shows, a Daihatsu Fourtrak 170 hardtop can be yours for £9,660 ex-VAT; the larger Isuzu Trooper in van guise costs over .210,000.

At the moment, the bottom end of the market is held by products from Eastern Europe. With the dramatic changes taking place there, and the amount of money Western manufacturers are investing, it's a fair bet that by the year 2000 cheap vehicle production will have moved to fresh fields in India, Malaysia or somewhere else with a low cost base.

But for now the choice of basic all-terrain vehicles for under 26,000 is limited to the Romanian Dacia Duster Hardtop (24,999 in petrol form) and the Russian Lath Niva van which, at £5,474, is the subject of this week's test.

The Niva, which is produced by VAZ at its Togliatti plant, is no stranger to these shores. It made its UK debut in 1978 as a passenger vehicle in left-handdrive only.

Since then the steering wheel has swapped sides, and since December 1986 it has been available as a van.

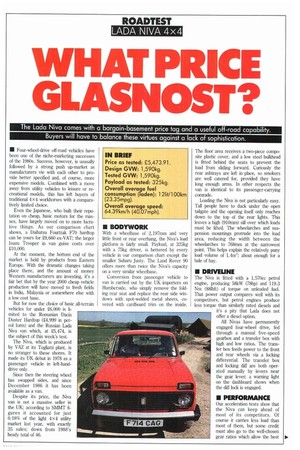

Despite its price, the Niva van is not a massive seller in the UK; according to SMMT figures it accounted for just 0.18% of the light 4x4 utility market last year, with exactly 35 sales; down from 1988's heady total of 46. With a wheelbase of 2,197mm and very little front or rear overhang, the Niva's load platform is fairly small. Payload, at 325kg with a 75kg driver, is bettered by every vehicle in our comparison chart except the smaller Subaru Justy. The Land Rover 90 offers more than twice the Niva's capacity on a very similar wheelbase.

Conversion from passenger vehicle to van is carried out by the UK importers on Humberside, who simply remove the folding rear seat and replace the rear side windows with spot-welded metal sheets, covered with cardboard trim on the inside. The floor area receives a two-piece composite plastic cover, and a low steel bulkhead is fitted behind the seats to prevent the load from sliding forward. Curiously the rear ashtrays are left in place, so smokers are well catered for, provided they have long enough arms. In other respects the van is identical to its passenger-carrying comrade.

Loading the Niva is not particularly easy. Tall people have to duck under the open tailgate and the opening itself only reaches down to the top of the rear lights. This leaves a high (910mm) sill over which loads must be lifted. The wheelarches and suspension mountings protrude into the load area, reducing the width between the wheelarches to 768mm at the narrowest point This helps explain the relatively puny load volume of 1.4m2; about enough for a bale of hay.

The Niva is fitted with a 1,570cc petrol engine, producing 58kW (78hp) and 119.3 Nm (88lbft) of torque on unleaded fuel. That power output compares well with its competitors, but petrol engines produce less torque than similarly rated diesels and it's a pity that Lada does not offer a diesel option.

All Nivas have permanently engaged four-wheel drive, fed through a manual five-speed gearbox and a transfer box with high and low ratios. The transfer box feeds power to the front and rear wheels via a locking differential. The transfer box and locking dill are both operated manually by levers near the gear lever, a warning light on the dashboard shows when the dill lock is engaged. use to be made of the available power. The clutch action is on the heavy side, but not intolerably so, and the gear leaver moves through a well defined gate.

When cold, however, the shift baulks badly on changes from first to second, making it very difficult to move the lever out of first gear. Once the oil has warmed up this problem seems to disappear, but the synchromesh is generally weak. This is most noticeable on upward changes into second and fourth gears where crunch-free shifts cannot be guaranteed.

Otherwise the gearchange is light and pleasant, and if Lada beefed up the synchromesh a bit the gearbox would be worthy of high praise.

The transfer box and diff-lock levers are operated with reasonable ease, without recourse to the two-hands-on-the-lever-andone-foot-on-the-dashboard technique required by some of the Niva's rivals. With its permanent four-wheel drive and a choice of ratios the Niva had no difficulty restarting on our 33% (1:3) test hill.

With a gearbox, transfer box and three sets of crownwheels and pinions whirring round, progress is bound to be noiser than in a vehicle with only one driven axle, but the word "noisier" does not adequately describe the siren-like wailing that accompanies forward motion in the Niva.

Commuters on London's Metropolitan and Circle underground lines would be instantly familiar with the sound: a low frequency whine quickly joined by higher pitched noises as the train pulls away. Most people can tolerate that for a few stops on the tube, but travelling any distance in the Niva becomes a tiresome experience, particularly at motorway speeds where it was best to forget about the optional-extra radio altogether. The engine, though not particularly refined, was drowned out by the transmission noise.

With its comparatively small petrol engine the Niva was never likely to win any fuel

economy prizes, but our laden figure of 12.00111100km (23.35mpg) is not too bad for a vehicle of this type. A diesel engine with a similar power output would probably offer improved fuel consumption as well as extra torque.

Servicing the Niva should not present any particular problems. Under-bonnet access to service items is good, although it might be necessary to remove the spare wheel to reach some engine parts. Mind you, stowing the spare wheel under the bonnet does make it easily accessible, as we found out during testing when a carelessly discarded bottle brought the Niva hissing to a halt. The jack lives under the bonnet too and easily lifted the Lada high enough to change the wheel without using blocks. A comprehensive tool kit comes with every Niva, which is a boon in a vehicle designed for off-road use.

When Motor magazine tested the Niva back in 1978, it described the on-road steering as "surprisingly light". Compared with its four-wheel-drive contemporaries that may have been so, but in 12 years our expectations have been raised. On the road the worm-and-roller steering is heavy, stodgy and vague with excessive free play. The large, thin-rimmed steering wheel can easily slip through the driver's hands, particularly when heaving on lock at parking speeds.

The roadholding doesn't generally inspire much confidence. A high centre of gravity and long suspension travel causes the Niva to lurch into bends with a fair amount of body roll, particularly when laden. By way of contrast the ride is well controlled thanks to independent front suspension with an anti-roll bar and coil springs controlled by telescopic dampers all round.

The brakes do not inspire much more confidence than the roadholding, despite looking good on paper.