A trip down memory lane

Page 39

Page 41

Page 43

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

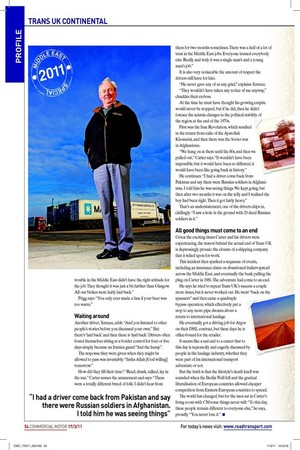

Bob Carter’s Trans UK Continental was a magnet in the 1970s for young men seeking adventure in countries such as Iraq, Iran and Pakistan. CM meets the men that found it

Words: Chris Tindall / Images: Stuart Wood

The sun is bolting towards the horizon as you make your way along the Khyber Pass in a Fiat 170.

You know the Pakistani government will soon seal off the route for the night, but when you spy a group of men trying to free their vehicle from a ditch, you also know you can’t leave them struggling.

For Mick Prigg, ex-driver of Bob Carter’s legendary Trans UK Continental, it’s a no-brainer and so he jumps out of his cab to help.

This would turn out to be a wise move.

The men were Mujahideen: Muslim fighters who knew the surrounding mountains like the backs of their hands.

The rebels reward his help by escorting his lorry to the Pakistani border, all the while signalling to hidden Mujahideen with their eerie whistles in the growing darkness that it was safe for him to pass.

Carter is in his living room listening to this anecdote resurrected from the heyday of his transport operation in the 1970s before saying: “You can’t comprehend the difference in mindset of the blokes that did that sort of work.” It is difficult. The astonishing stories come thick and fast as he and his drivers reminisce about a time when young men with an almost pathological quest for adventure agreed without hesitation to drive to far flung countries like Iran, Afghanistan, Kuwait and Iraq. Mundane interruptions from this journalist about how on earth you schedule jobs that either lasted weeks or months depending on the success or otherwise of bribes, mechanical knowledge and the ability to remain calm under pressure only prove Carter’s point: “What schedule?” they chorus.

It was very definitely another world. Carter started the Felixstowe company at the end of November 1970. At first he relied solely on subbies to do domestic container work, but in his words “things gradually grew” . Next began groupage to Germany and then he was asked if the company would have a crack at the Middle East, specifically Abadan in Turkmenistan, and Tehran.

Istanbul in 5 days

“Two or three people I knew said they wanted to go,” he says. “We didn’t put pressure on anybody. I went with them in my car. I wanted to find an agent.

“We hit Istanbul in five days. Then we were at Tehran Customs six days after that. We waited four or five days to empty and then came back home fairly quickly.” As the business expanded, his drivers began hauling anything from white goods to Pakistan, chicken huts and tractors to Turkey, and electrical goods, oxygen bottles and pipe tape to Iran. “We didn’t market ourselves necessarily,” he says. “We relied on word of mouth for customers. We did a good service, and then word got round. We would go anywhere that would pay the rate. But we were also quite fussy who we worked for.” According to Carter, the key to Trans UK’s success was two-fold: the first was finding agents along the route who they could trust and who could help if drivers hit a spot of bother (“It pays to have good people in bad places”); second was each driver’s red book, naturally referred to as their bible.

The driver’s ‘bible’

The red book was a comprehensive file of maps, routes, mileages, documents, useful local information and addresses that Carter accumulated and gave to his drivers after he himself had first undertaken the journey.

Finding backloads was never a problem. Carter says there was more return work available in Yugoslavia than Trans UK could handle: “We used to load tractors out of Belgrade to go to the UK. We did a few loads of jam and apples, but that wasn’t worth it. We concentrated on the huge flow of bicycles out of Yugoslavia and tractors, and that was enough to fill all our trucks and probably the same again for subbies. Or you could run into Germany; you could always get something back.” Drivers were not immediately sent off to these far-off countries, no matter how much they might plead. They had to prove themselves to Carter on domestic work first, then with loads on the Continent before he would send them on a 14,500-mile round trip to Pakistan.

The stories keep on coming. There is the one about the driver bitten by a wild dog in eastern Turkey and who had to be flown home for fear he had contracted rabies; the drivers who hastily stuffed their pockets full of thousands of deutsche marks in Istanbul as payment for the load of bicycles just delivered; 24-page carnets and 55-mile queues into Baghdad; minus 40-degree temperatures along treacherous icy roads and the extreme heat in Jordan that made the roads slide down mountains and melt into viennetta loops of Tarmac at the bottom. You might wonder about the type of driver that agreed to take on this sort of work. As well as comments about wanderlust, decent pay and the fun to be had, there is also an indication of the temperament needed: “It wasn’t everyone’s cup of tea,” admits Carter.

“I went to Turkey with someone once: he would lose his rag with coppers. I would say half the blokes who got into trouble in the Middle East didn’t have the right attitude for the job. They thought it was just a bit further than Glasgow. All our blokes were fairly laid back.” Prigg says: “You only ever made a fuss if your beer was too warm.”

Waiting around

Another driver, Terence, adds: “And you listened to other people’s stories before you discussed your own.” But there’s ‘laid back’ and then there is ‘laid back’ . Drivers often found themselves sitting at a border control for four or five days simply because an Iranian guard “had the hump” .

The response they were given when they might be allowed to pass was invariably: “Insha Allah [God willing] tomorrow.” How did they fill their time? “Read, drank, talked, lay in the sun.” Carter senses the amazement and says: “These were a totally different breed of folk. I didn’t hear from them for two months sometimes. There was a hell of a lot of trust in the Middle East jobs. Everyone trusted everybody else. Really and truly it was a single man’s and a young man’s job.” It is also very noticeable the amount of respect the drivers still have for him.

“He never gave any of us any grief,” explains Terence. “They wouldn’t have taken any notice of me anyway,” chuckles their ex-boss.

At the time he must have thought his growing empire would never be stopped, but if he did, then he didn’t foresee the seismic changes in the political stability of the region at the end of the 1970s.

First was the Iran Revolution, which resulted in the return from exile of the Ayatollah Khomeini, and then there was the Soviet war in Afghanistan.

“We hung on in there until the 80s, and then we pulled out,” Carter says. “It wouldn’t have been impossible, but it would have been so different; it would have been like going back in history.” He continues: “I had a driver come back from Pakistan and say there were Russian soldiers in Afghanistan. I told him he was seeing things. We kept going, but then after two months it was on the telly and I realised the boy had been right. Then it got fairly heavy.” That’s an understatement, one of the drivers chips in, chillingly: “I saw a hole in the ground with 20 dead Russian soldiers in it.”

All good things must come to an end

Given the exciting times Carter and his drivers were experiencing, the reason behind the actual end of Trans UK is depressingly prosaic: the closure of a shipping company that it relied upon for work.

This incident then sparked a sequence of events, including an insurance claim on abandoned trailers spread across the Middle East, and eventually the bank pulling the plug on Carter in 1981. The adventure had come to an end.

He says he tried to repeat Trans UK’s success a couple more times, but it never worked out. He went “back on the spanners” and then came a quadruple bypass operation, which effectively put a stop to any more pipe dreams about a return to international haulage.

He eventually got a driving job for Argos on their DHL contract, but these days he is office-bound for the retailer.

It seems like a sad end to a career that to this day is repeatedly and eagerly discussed by people in the haulage industry, whether they were part of his international transport adventure or not.

But the truth is that the lifestyle’s death knell was sounded when the Berlin Wall fell and the gradual liberalisation of European countries allowed cheaper competition from Eastern European countries to spread.

The world has changed, but for the men sat in Carter’s living room with CM some things never will: “To this day, these people remain different to everyone else,” he says, proudly. “You never lose it.” ■