A DOUBLE-DECKER

Page 120

Page 121

Page 122

Page 123

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

of DISTINCTION W1THOUT doubt the introduction of the Fluid Flywheel and self-changing gearbox, as a combination, for duty in Daimler passenger-carrying chassis was one of the technical milestones of 1930. For several years the CFG chassis had been building up a reputation; this was followed by the C06 with a conventionaletransmission, and then the 0116 was added to the range. The last-named resembles the improved CG6, but embodies the new transmission system. We have, on several occasions, had experience of the new type, but recently a fully laden chassis was put through our standard one-day test, thus enabling us to obtain more comprehensive data regarding it. A chassis equipped with a demon

stration body and test ballast, having a gross weight of Di tons, was placed at our disposal; its mileage up to that time was 3,500. The chassis was standard in every respect; it, of course, embodied the Daimler six-cylindered sleeve-valve engine with a. vibration damper, an oil-cooling system, oil priming (for cold starting) and pressure-lubricated gudgeon pins. The frame was of the low-loading variety. It is worth noting that the chassis weight is 3 tons 7 cwt.—a figure a few hundredweight lower than is often the case; this result is obtained by scientific application el the latest knowledge regarding the use of aluminium alloys.

Before the test the chassis was weighed and the results are shown in the accompanying panel. It will be realized that the gross weight was midway between the old and new weight limits for vehicles of this class ; it was laden to a weight about 5 cwt. greater than that of most double-deckers at present in use.

After leaving the works of the Daimler Co., Ltd., Coventry, traffic was encountered for two or three miles. In narrow streets, with buildings close to the road, any whine from the gearbox would be definitely brought into prominence, lout no matter what gear was in use in the streets of Coventry, the engine note predominated. As most of our readers will be aware of the silence of the Daimler engine, they will realize that this means a high standard of transmission quietness. To the bus passenger this quality means the chance for easy conversation or reading, to the driver it means a reduction of nerve strain and to the operator reduced maintenance costs. A few experiments showed that the gear-engaging pedal, which replaces the clutch pedal, could be treated without delicacy. Even stamping on the pedal to engage a gear gave rise to no jerk in the transmission. From this point of view a tired or careless driver cannot be distinguished for his lack of finesse.

The other transmission control_ the pre-selector lever on the steering column—was operated with certainty by one finger. The gearchange sequence is as follows:— Move the lever from neutral to the desired position, operate the gearengaging pedal and then accelerate. Until the engine attains COO r.p.m. the vehicle does not begin to move, then it gathers speed smoothly and surely.

Subsequent changes are effected by moving the lever to the desired position, taking the foot off the accelerator or keeping it steady— according to whether the change is upwards or downwards—and then operating the gear-engaging pedal. We found that no judgment of engine speeds was necessary to make a smooth change, it simply being necessary to raise the foot from the accelerator or to keep it steady.

Even if these simple rules be ignored and the engine speed be grossly in error, the Fluid Flywheel definitely cuts down the shock to about 25 per cent. of that which would be imparted by a clutch.

Any gear can be pre-selected and engaged when the desired moment

arises ; there is no need to use the gears progressively—a change from first to top, or vice versa, is permissible. As a safety factor, the Daimler system has many merits, because the driver need not take his eyes off the road ; the physical and mental efforts required for a change are almost negligible and both hands can be kept on the wheel. This means that driving fatigue is much reduced.

A stop can be made at any time simply by releasing the accelerator ; there is no need to return to neutral. A restart can be made on any gear merely by accelerating, providing the gradient is not too steep for the gear in question. One graph which we publish shows the striking ability of the bus to attain 40 m.p.h. from rest in 50 secs., using only top gear. This does not strain the Fluid Flywheel as it would do the ordinary clutch.

It is important to note that the ability to use the engine as a brake is not sacrificed. Over-running is positive but sweet. On a hill of 1 in 5 we let the vehicle run slowly backwards merely against the engine —no brakes were used. On the ascent of this hill the machine was held without brakes solely by letting the engine pull slowly against first gear, the Fluid Flywheel allowing the necessary slip ; after such D52 treatment its casing was not too hot to touch.

On a 1-in-5 gradient the vehicle restarted easily, forward or backward, without engine racing; on lin 10 it restarted in second gear. When climbing Warmington Hill (1 in 10) second gear sufficed for the steepest portion, third gear being re-engaged just above the church. To climb long gradients silently on any gear proved to be a realised ambition

with the CH6. The road speed,

water temperature (170 degrees F.) and fuel return (6.74 m.p.g.) show'xl that the transmission was not giving this commendable performance at the expense of undesirable slip.

As regards acceleration, the graphs speak for themselves; these figures were obtained with the engine set to give 83 b.h.p.—a comparatively low figure for such a large machine. This course is taken in the interests of the operator ; he thus obtains long vehicle life and low fuel consumption.

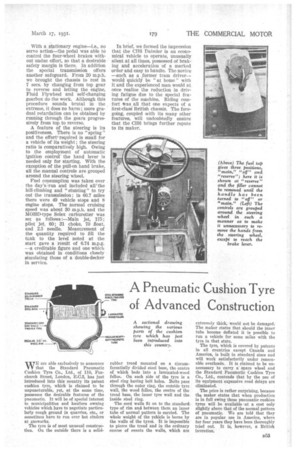

Braking efficiency, as revealed by the appropriate graph, was of a high order. Both the hand lever and the pedal—actuating a Dewandre servo —were easily operated, and either would hold the vehicle on a 1-in-5 gradient. There was no " grabbing " and no tendency for any brake to take more than its share of the load. The rear-wheel shoes of: the service brake are 34 ins, wide and those of the front-wheel sets 2i ins; wide. The hand-brake shoes -are 2 ins. wide. With a _stationary engine—i.e., no servo action—the pedal was able to control the four-wheel brakes without undue effort, so that a desirable safety margin is there. In addition the special transmission offers another safeguard. From 20 m.p.h, we brought the chassis to rest in 7 secs. by changing from top gear to reverse and letting the engine, Fluid Flywheel and self-changing gearbox do the work. Although this procedure sOunds brutal in the extreme, it does no harm ; more gradual retardation can be obtained by running through the gears progressively from top to reverse.

A feature of the steering is its positiveness. There is no " spring " and the effort, required is small for a vehicle of its weight ; the steering ratio is comparatively high. Owing to the employment of automatic ignition controlthe hand lever is needed only for starting. With the exception of the pull-on hand brake, all the manual controls are grouped around the steering wheel.

Fuel consumption was taken over the day's:Tun and included all-the hill-climbing and " stunting" to try out the transmission; in 60.7 miles there were 49 vehicle stops and 8 engine stops. The normal cruising speed was about 30 m.p.h. and the MOHD-type Solex carburetter was set as follows :—Main jet, 175; pilot jet, 60; 31 choke, 70 foal, and 2.5 needle. Measurement of the quantity required to fill the tank to the level noted at the start gave a result of 6.74 m.p.g. —a creditable figure and one which was obtained in conditions closely simulating those of a double-decker in service.

• In brief, we formed the impression that the C116 Daimler is an economical vehicle to operate, unusually silent at all times, possessed of braking and acceleration of a marked order and easy to handle. The novice —such as a former train driver— would quickl3f be "at home" with it and the experienced man would at once realize the reduction in driving fatigue due to the special features of the machine. Riding comfort /vas all that one expects of a first-clasi British chassis. The foregoing, coupled with its many other features, will undoubtedly ensure that the CH6 brings further repute to its maker.