Buses Aid Madrid's Expansion

Page 42

Page 43

Page 44

Page 47

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

WNY delegates from other countries who attended the 1953 Congress of the International Union of Public Transport in Madrid retired to their siestas with envious thoughts about the advantageous effect that this national habit had on multiplying the passenger-traffic peak hours, and decided that under similar favourable conditions they could organize their own fleets to show a profit instead of a loss.

Closing the shops and ceasing work from 1.30 p.m. to 4 p.m. would be useless as a means for transferring the afternoon work period to the more invigorating hours between 4 p.m. and 7 p.m. unless the transport system was adequate to carry the rest-seeking passengers. Moreover, the extension of the useful hours of leisure for the masses to the early hours of the morning would fail to serve its purpose if the people had to walk home. And many people with their families can afford a regular night out, sipping an inexpensive drink at a pavement table while watching the crowds.

All these factors contribute to a sustained movement of passengers, for which the Madrid transport system ably caters, and even if television were ultimately introduced it would be unlikely to represent the threat to evening traffic that it appears to do in many British towns. It is not altogether surprising, therefore, that the siesta of delegates from colder climates was often preceded by disturbing comparisons.

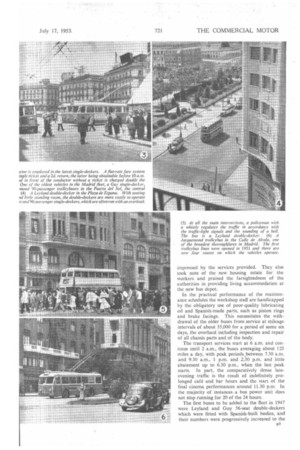

When the private companies of the Madrid transport services were taken over by the corporation in 1947 and unified by the transport department (Empresa Municipal de Transportes) there were only three routes on which motorbuses were used. The first measures adopted by the authorities included the replacement of trams by motorbuses on the routes running through the central city area. Trolleybuses were introduced in 1951, and today 14 motorbus and four trolleybus services are operated in addition to 36 tram routes, a number of which has been replaced by motorbuses in outlying areas. as In 1952 nearly 68m. passengers were carried a distance of over 4.3m. miles by the bus fleet of 150 vehicles, compared with proportionately higher passenger and mileage figures for the 400 trams. The passengers on the underground railway numbered over 347m.

Madrid is a city of multi-storied buildings and has a high population density. In 1940 about im. people were contained within an area of 45 sq. miles and by January, 1953, the population had risen to over 1.7m. and the area had increased to 225 sq. miles.

IndUstrial expansion has been encouraged, and although the number of employees in any works does not exceed a few hundred (the new .Pegaso works at Barajas will eventually employ some thousands) this trend, combined with the building of many housing estates has created a demand for further bus services in suburban areas. At the same time, the first cost of the vehicles and the costs of fuel and

lubricating Oil have greatly increased. Currency difficulties persist and the replacement of vehicles and the provision of spares presents an acute economic problem.

During the congress, some delegates made unfavourable comments on the standard of maintenance and repeated rumour that the most modern buses in the fleet were being run in the central area to impress visitors. Others who could assess present achievement against the background of the civil war and the disturbances of pre-war days were favourably impressed by the services provided. They also took note of the new housing estate for the workers and praised the farsightedness of the authorities in providing living accommodation at the new bus depot.

In the practical performance of the maintenance schedules the workshop staff are handicapped by the obligatory use of poor-quality lubricating oil and Spanish-made parts, such as piston rings and brake facings. This necessitates the withdrawal of the older buses from service at mileage intervals of about 35,000 for a period of some six days, the overhaul including inspection and repair of all chassis parts and of the body.

The transport services start at 6 a.m. and continue until 2 a.m., the buses averaging about 125 miles a day, with peak periods between 7.30 a.m. and 9.30 a.m., 1 p.m. and 2.30 p.m. and little abatement up to 6.30 p.m., when the last peak starts. In part, the comparatively dense lateevening traffic is the result of indefinitely prolonged café and bar hours and the start of the final cinema performances around 11.30 p.m. In the majority of instances, a bus power unit does not stop running for 20 of the 24 hours.

The first buses to be added to the fleet in 1947 were Leyland and Guy 56-seat double-deckers which were fitted with Spanish-built bodies, and their numbers were progressively increased to the present figures of 50 Leylands and 30 Guys. The earlier chassis have covered great mileages under severe operating conditions and these will, in due course, be replaced.

Of the remaining 30 motorbuses in regular service, Renault 80-passenger underfloor-engined single-deckers with French-built bodies form the majority, a small number of Leyland and Guy single-deckers being used for stand-by work.

All the 33 trolleybuses are French 90-passenger singledeckers of Jacquemond manufacture with bodies by the chassis makers. The motors are Maison Brequet compound-wound units developing 110 h.p. at 1,500 r.p.m. (a slightly higher power would be preferred), which are mounted at the rear. Some are fitted with a gearbox take-off for the compressor and generator and all are designed to provide regenerative braking.

Batteries provide the current for manoeuvring purposes. The Renault buses are nearly 35 ft. long and a little over 7 ft. 6 in. wide.

There are 25 seats and the nominal standing capacity of 55 passengers is often exceeded.

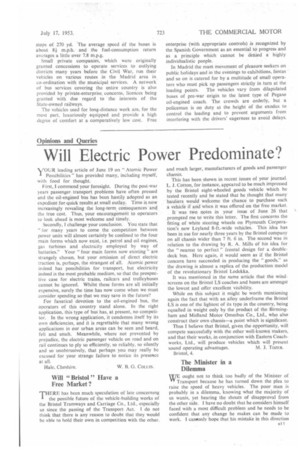

On all the latest single-deck buses a seated conductor controls the power operated doors of the central entrance. Passengers pay their fares when passing the conductor's counter, and if anyone is found in the front of the bus without a ticket he is charged double the normal amount_ Attempts to evade payment are consequently rare.

A flat-rate single fare of rather more than lid, is charged, but passengers starting a journey before 10 a.m. can obtain a return ticket at a cost of 2d. In 1952 the takings per passenger averaged 1.48d. in the motorbuses and 1.49c1. in the trolleybuses. The cheap return fare is described as a " political " or sub-economic fare; the single fare would cover costs if it were generally applied. Flat rates at about half the price are charged on the trams.

The introduction of three-door motorbuses and • trolleybuses has had gratifying results on the speed of loading and unloading. Because of their greater capacity and the shorter time occupied at the stops, the single-deck buses are relatively more economical to operate than the double-deckers. The Renaults are proving satisfactory in service, but as they have not covered a sufficient mileage to require major mechanical overhauls, comparative maintenance costs are not available.

The Renault engine develops a nominal brake horsepower of 105 at 2,500 r.p.m., but at the Madrid altitude of 2,400 ft. the power available is reduced. The unladen weight of the bus is over 7 tons 7 cwt., and as all the routes are hilly a power unit developing up to 135 b.h.p. would be more suitable. Despite this requirement, however, the five forward ratios of the gearbox (actuated by a lever on the steering column) are considered unnecessary. Three ratios would be adequate.

Bodywork features of the Renaults, which are of integral construction, include a double-skinned ventilated ‘310 roof with a perforated inner panel, and in the latest three-door type air flovv is assisted by a fan.' The full-depth fixed windscreen, in conjunction with deep quarter lights, gives excellent visibility. Hinged sun visors above the windscreen are tinted blue and similar tinting is used for the glasses of the two interior roof lights immediately behind the driver's compartment.

Smoking is forbidden in all the buses and it is against the rules to speak to the driver. Passengers may, however, stand at the front exit, where a grab rail is provided.

An unusual kind of bonus for freedom from accident is awarded to drivers. Slightly higher rates are given to married men and an additional payment for each son. A basic bonus of 2s. 7d. a day is paid for .a full day's work and a proportionate amount for a reduced number

of journeys. In addition to this there is a monthly bonus of £2 14s. (300 pesetas), and the potential financial gain in a year represents an appreciable part of the total wage. Here the incentive bonus does seem economic. ' The care, skill and courtesy of drivers in the central streets of Madrid are outstanding to an interested observer. By British standards conditions sometimes approach the chaotic, particularly with regard to the noise at intersections. A policeman with a strident whistle is on duty to supplement the directive influence of the traffic lights, which change to the accompaniment of loud bell-ringing. Unlike many of the other road users, the bus drivers appear to be unruffled by such distracting influences.

As already indicated, poor lubricating oil greatly increases maintenance costs. Comparative tests with high-grade oils have shown that the normal interval between changes of less than 2,000 miles could be more than doubled if better-quality lubricant were readily available. A proportionate increase in engine life between overhauls could also be expected.

The oil fuel used is of a similar inferior quality and tends to clog the filters after a short running period. A great improvement is, however, obtained by treating the oil in a centrifuger operating at 16,000 r.p.m.

Spanish-made tyres are used exclusively, because their production exceeds demand. Their quality is comparable with that of the average imported covers and a mileage of about 50,000 is obtained between replacements or retreading, despite a normal distance between stops of 270 yd. The average speed Of the buses is about 81 m.p.h. and the fuel-consumption return averages a little over 7.8 m.p.g.

Small private companies, which were originally granted concessions to operate services to outlying districts many years before the Civil War, run their vehicles on various routes in the Madrid area in co-ordination with the municipal services. A network of bus services covering the entire country is also provided by private-enterprise, concerns, licences being granted with due regard to • the interests of the State-owned railways.

The vehicles used for long-distance work are, for the most part, luxuriously equipped and provide a high degree of comfort at a comparatively low cost. Free enterprise (with appropriate controls) is recognized by the Spanish Government as an essential to progress and as a principle which cannot be denied a highly individualistic people.

In Madrid the mast movement of pleasure seekers on public holidays and in the evenings to exhibitions, fiestas and so on is catered for by a multitude of small operators who must pick up passengers strictly in turn at the loading points. The vehicles vary from dilapidated buses of pre-war origin to the latest type of Pegaso oil-engined coach. The crowds are orderly, but a policeman is on duty at the height of the exodus to control the loading and to prevent arguments from interfering with the drivers' eagerness to avoid delays.