COPING WITH THE HAZARDS

Page 42

Page 43

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

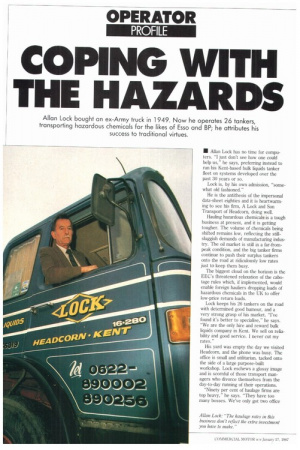

Allan Lock bought an ex-Army truck in 1949. Now he operates 26 tankers, transporting hazardous chemicals for the likes of Esso and BP; he attributes his success to traditional virtues.

• Allan Lock has no time for computers. "I just don't see how one could help us," he says, preferring instead to run his Kent-based bulk liquids tanker fleet on systems developed over the past 30 years or so.

Lock is, by his own admission, "somewhat old fashioned."

He is the antithesis of the impersonal data-sheet eighties and it is heartwarming to see his firm, A Lock and Son Transport of Headcom, doing well.

Hauling hazardous chemical is a tough business at present, and it is getting tougher. The volume of chemicals being shifted remains low, reflecting the stillsluggish demands of manufacturing industry. The oil market is still in a far-frompeak condition, and the big tanker firms continue to push their surplus tankers onto the road at ridiculously low rates just to keep them busy.

The biggest cloud on the horizon is the EEC's threatened relaxation of the cabotage rules which, if implemented, would enable foreign hauliers dropping loads of hazardous chemicals in the UK to offer low-price return loads.

Lock keeps his 26 tankers on the road with determined good humour, and a very strong grasp of his market. "I've found it's better to specialise," he says. "We are the only hire and reward bulk liquids company in Kent. We sell on reliability and good service. I never cut my rates."

His yard was empty the day we visited Headcorn, and the phone was busy. The office is small and utilitarian, tacked onto the side of a large purpose-built workshop. Lock eschews a glossy image and is scornful of those transport managers who divorce themselves from the day-to-day running of their operations.

"Ninety per cent of haulage firms are top heavy," he says. They have too many bosses. We've only got two office staff here and we manage to do everything."

Lock is a self-made man and the company has grown from a single ex-army Guy Vixant he bought in 1949. He is still the company's driving force. "I think personal contact is the main thing," he says. "Ring here and 99% of the time I pick up the phone. The people we contract for like to know that they can always talk to me." He has some impressive blue-chip customers, and regularly hauls for BP, Esso, and the large solvent braking group, Gelpke and Bate.

Some 80% of Lock's loadings come out of Purfleet, Essex on the Thames Estuary and two of his trucks run in customers' own colours. Lock likes to keep the rest in his own livery.

The firm carries a lot of petroleumbased liquids and industrial alcohols such as ethanol. It is a far cry from the early days when Lock bought his first post-war truck. "The brakes were awful — they were cable-only. I gained a fair bit of mechanical knowledge in those days — we used to spend as much time repairing as working."

Today he runs 20 MAN 20.321 threeaxle tractors, two DAF 2800s, two Scanias, a Leyland Clydesdale and an ERF C290. All are sleeper cabs. "We don't generally bother with overnight driving," says Lock, "the drivers are happier in their cabs."

OLD FASHIONED

his old-fashioned approach extends beyond the personal-touch image. Lock does not use any of the contract hire or leasing schemes currently dominating the industry.

"I've always bought my lorries on outright purchase," he says, "because I buy them to keep. Contract hire doesn't appeal to me at all. There will always come the day when the hired truck is left standing, and I would hate to sit here looking at it thinking 'that's costing me £200 a week'."

The company has no pre-determined depreciation period. Lock likes to run the fittest units for as long as possible. He has disposed of duff units in less then a year, but six years is the average.

"I try to make each vehicle pay for itself and for its replacement, but the haulage rates in this business don't reflect the extra investment you have to make. The large companies are so competitive — I don't really think that rates are suicidal at the moment, but they're pretty close to the bone."

Maintaining decent profitability in a market which requires high capital investment is no mean feat.

A new stainless steel tanker and twinsteer tractor unit costs more than £70,000. That is twice the cost most hauliers have to bear and does not include extras like driver training.

Lock outlines the investment a typical new tanker rig involves: "Stainless steel tanks are now around £35,000 each, and twin-steer tractor units another £35,000." Extra petrol requirements add a further £1,800 and a pump/compressor or power take-off unit another £1,500. Hoses and fittings will set you back about £350 with the whole rig amounting to 273,500.

Lock is philosphical about the hazardous chemicals transport market. "Profits should be greater," he says, "but it becomes a way of life."

He insists that his drivers know what they are doing and the value of the vehicle they are running. If anything ever does go wrong, the one-hectare site at Headcorn has its own workshops. Lock helped build the servicing area and likes to keep as much work as possible inhouse. He feels that it is more costeffective for his situation.

Of the 26 full-time drivers on Lock's books, several have been with the firm for more than 20 years. He appreciates that level of reliability.

"All our drivers are Hazchem trained," he says, "they have to be. It costs though — I mean, you're looking at about £130 every three years per driver for courses to keep them up to date."

He realises that some of the drivers find it hard to learn all the different symbols and their meanings, but he regards their training courses as essential. "The whole business is very complicated. I think it could all be simplified quite easily — especially the labelling. I prefer the Kembler scheme, which is the scheme used on the Continent. On the boards you have a '3' for hazardous, '2-3' for very hazardous, and so on."

Lock handles a small amount of international haulage, mainly to northern Europe. "Customs can be a real pain," says Lock. "If we go through Dover in four to six hours we think we're lucky. It often takes about 14 hours and that costs us a hell of a lot of money. What frustrates me is you can never really pinpoint the problem or talk to customs."

The company books are kept up to date by Lock's accountant-cum-personal assistant and he says, "I know where I am all the time."

Problems always arise when the authorities change the regulations, but other than that Lock seems to have got the situation taped. He is modest about the way the company has grown and his involvement in that growth.

Having built up the company from scratch, it is clear that Lock stays firmly in control because he has done every job himself at some point.

It seems unlikely that the firm will move away from the hydrocarbons, ethanols, industrial paints and lubricants it carries today. "We used to do some milk haulage," says Lock, "but they only use you when they're busy, like at Christmas. Then they drop you like a brick and you never hear any more."

Talk in the industry at present centres around the possible introduction of ADR continental-style tankers. These more expensive units would have to be used for many chemicals which can currently be transported in the UK in general-purpose tankers.

HIS OWN BOSS

He likes being his own boss. "I've had several offers to buy me out," he says, "but I haven't got round to it yet. That's all you hear about nowadays — takeovers."

Though he is obviously canny, Lock is not really the conservative he might appear. The business still excites him.

"I think we're about the right size now," he says. "Mind you, I said that when we had ten vehicles."

by Geoff Hadwick