Freightliners Challenge or Opportunity?

Page 60

Page 61

Page 62

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

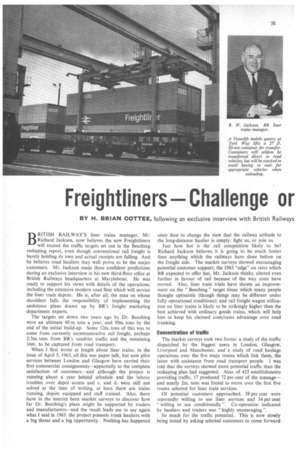

BY H. BRIAN COTTEE, following an exclusive interview with British Railways BRITISH RAILWAY'S liner trains manager, Mr. Richard Jackson, now believes the new Freightliners will exceed the traffic targets set out in the Beeching reshaping report, even though conventional rail freight is barely holding its own and actual receipts are falling. And he believes road hauliers may well prove to be the major customers. Mr. Jackson made these confident predictions during an exclusive interview in his new third-floor office at British Railways headquarters at Marylebone. He was ready to support his views with details of the operations, including the extensive modern road fleet which will service the liner train depots. He is, after all, the man on whose shoulders falls the responsibility of implementing the ambitious plans drawn up by BR's freight marketing department experts.

The targets set down two years ago by Dr. Beeching were an ultimate 40 m. tons a year, and 30m. tons by the end of the initial build-up. Some 12m. tons of this was to come from currently unremunerative rail freight, perhaps 2/3m. tons from BR's sundries traffic and thel remaining 16m. to be captured from road transport.

When I first wrote at length about liner trains, in the issue of April 5, 1963, all this was paper talk, but now pilot services between London and Glasgow have carried their first commercial consignments—apparently to the complete satisfaction of customers—and although the project is running about a year behind schedule and the labour troubles over depot access and c. and d. were still not solved at the time of writing, at least there are trains running, depots equipped and staff trained. -Also, there have in the interim been market surveys to discover how far Dr. Beeching's plans might be supported by traders and manufacturers—and the result leads me to say again what I said in 1963: the project presents trunk hauliers with a big threat and a big opportunity. Nothing has happened

since then to change the view that the railway attitude to the long-distance haulier is simply: fight us, or join us.

Just how hot is the rail competition likely to be? Richard Jackson believes it is going to be much hotter than anything which the railways have done before on the freight side. The market surveys showed encouraging potential customer support; the 1963 "edge" on rates which BR expected to offer has, Mr. Jackson thinks, altered even further in favour of rail because of the way costs have moved. Also, liner train trials have shown an improvement on the " Beeching " target times which many people thought optimistic (though things may be different under fully operational conditions); and rail freight wagon utilization on liner trains is likely to be strikingly higher than the best achieved with ordinary goods trains, which will help him to keep his claimed costs/rates advantage over road trunking.

Concentration of traffic The market surveys took two forms: a study of the traffic dispatched by the biggest nsers in London, Glasgow, Liverpool and Manchester, and a study of road haulage operations over the five main routes which link them, the latter with assistance from road transport people. I was told that the surveys showed more potential traffic than the reshaping plan had suggested. Also, of 425 establishments providing traffic, 17 produced 72 per cent of the tonnage— and nearly 2m. tons was found to move over the first five routes selected for liner train services.

Of potential customers approached, 58 per cent were reportedly willing to use liner services and 34 per cent "willing to use conditionally ". Co-operation indicated by hauliers and traders was "highly encouraging ".

So much for the traffic potential. This is now slowly being tested by asking selected customers to come forward with actual goods—as Richard Jackson put it: "The time comes when you have to put the wooden swords away." The wooden swords in his case have been tons of canned vegetables obtained by BR, old steel rails, waste paper, scrap chairs, bottles, anything available in fair quantity to give container loads of varying density and centre of gravity during trial runs.

Dr. Beeching's original cost studies (on the admittedly unrealistic basis of 100 per cent loading both ways) suggested that direct rail costs for liner trains would be about 20s. to 25s. per capacity ton lower than road freight costs over a 300-mile journey, and about half that amount of advantage at 200 miles. Wages have gone up on both sides since then, and so have many other things, but Mr. Jackson told me he believed that the advantage had shifted even further in BR's favour. He instanced higher vehicle tax, and higher maintenance costs to meet public pressure on vehicle condition, as factors which have enabled his rates to become newly competitive over lower mileages.

He recognizes the productivity and profitability advantages bestowed on hauliers by bigger vehicles under the new C. and U. regulations, as well as better chassis designs, new motorways and so on, but thinks he has one overriding thing in his favour which will become progressively more influential: while wage costs (and fringe benefits)

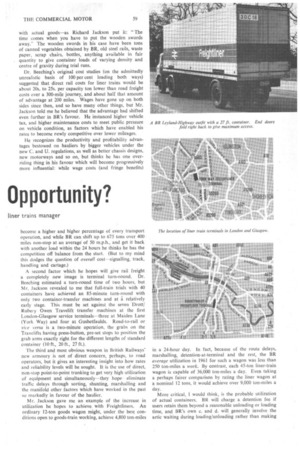

become a higher and higher percentage of every transport operation, and while BR can shift up to 675 tons over 400 miles non-stop at an average of 50 m.p.h., and get it back with another load within the 24 hours he thinks he has the competition off balance from the start. (But to my mind this dodges the question of overall cost—signalling, track, handling and cartage.) A second factor which he hopes will ,give rail freight a completely new image is terminal turn-round, Dr. Beeching estimated a turn-round time of two hours, but Mr. Jackson revealed to me that full-train trials with 40 containers have achieved an 85-minute turn-round with only two container-transfer machines and at a relatively early stage, This must be set against the seven Drott/ Rubery Owen Travelift transfer machines at the first London-Glasgow service terminals—three at Maiden Lane (York Way) and four at Gushetfaulds. Road-to-rail or vie versa is a two-minute operation, the grabs on the Travelifts having press-button, pre-set stops to position the grab arms exactly right for the different lengths of standard container (10 ft., 20 ft., 27 ft.).

The third and most obvious weapon in British Railways' new armoury is not of direct concern, perhaps, to road operators, but it gives an interesting insight into how rates and reliability levels will be sought. It is the use of direct, non-stop point-to-point trunking to get very high utilization of equipment and simultaneously—they hopeeliminate traffic delays through sorting, shunting, marshalling and the manifold other factors Which have worked in the past so markedly in favour of the haulier.

Mr. Jackson gave me an example of the increase in utilization he hopes to achieve with Freightliners. An ordinary 12-ton goods wagon might, under the best conditions open to goods-train working, achieve 4,800 ton-miles

in a 24-hour day, In fact, because of the route delays, marshalling, detention-at-terminal and the rest, the BR average utilization in 1961 for such a wagon was less than 250 ton-miles a week. By contrast, each 45-ton liner-train wagon is capable of 36,000 ton-miles a day. Even taking a perhaps fairer comparison by rating the liner wagon at a nominal 12 tons, it would achieve over 9,000 ton-miles a day.

More critical, I would think, is the probable utilization of actual containers. BR will charge a detention fee if users retain them beyond a reasonable unloading or loading time, and BR's own c, and d. will generally involve the attic waiting during loading/unloading rather than making

a double journey. But, even so, it is going to take constant pressure, and very tight administration, to keep the vital containers circulating properly. Tying up large capital to provide a big float of containers would be a sure way of boosting costs.

Already Glasgow-London services are operating with 15-wagon trains and York Way and Gushetfaulds depots are equipped to operational standard. If demand warrants, giant transporter cranes will replace the mobile Travelifts at some main depots eventually, the Travelifts then being moved to new and smaller terminals. The staff at both depots are now fully trained and the documentation has been worked out and tried in practice.

The Longsight terminal at Manchester is now just about finished, and the Garston depot at Liverpool is likely to be well on the way to completion by next spring.

Market research to test the traffic on the planned routes has been matched by calculations of traffic flow into the terminals (which has included computer time bought by BR), and Mr. Jackson was able to tell me the places chosen for the first 15 services—which will comprise Stage I of the liner trains project. And one of the most significant indications of how far the initial equipping has gone (at a cost of £1-73m. out of £.6m. allocated) is that within six months of the first full London-Glasgow service, all five of the initial routes should be running regularly.

These five are London-Glasgow, London-Manchester, London-Liverpool, Glasgow-Manchester and GlasgowLiverpool, in that order. All will run without intermediate stops, five days a week and will require seven permanently coupled train sets, each with 36/41 containers.

Which container sizes ?

Richard Jackson was having a quiet chuckle about this when

I saw him, as he had said originally that the trainloads would be of 36 rather than 40 or 41 containers, while market research suggested that the higher figures would be required because of the container sizes which customers would choose. He had just seen the requisition figures for the first batches of commercial traffic, and these backed his hunch: the 10 ft. 7-1-tonners and 27 ft. 20-tonners looked like being more popular than calculated, and the 20 ft 15-tonners less so. This raises a special problem in cartage circles, of which more anon.

The next 10 services will establish the initial network serving Aberdeen, Dundee, Glasgow, Edinburgh, Newcastle, Stockton, Leeds, Sheffield, Hull, Birmingham and Cardiff, in addition to the London, Manchester, Liverpool and Glasgow services in Phase I.

Although Mr. Jackson believes that solving the technical and traffic problems is a lot simpler than solving the human ones involved, two particular operational aspects have been very tricky to estimate, with no true precedent to go by. These are the proportions of traffic which will eventually be brought into Freightliner depots by hauliers, C-licensees and BR cartage respectively, and the likely popularity of the various lengths of standard 8 ft. by 8 ft. cross-section container—as already touched upon.

Despite a prediction that hauliers may well turn out to be the biggest customers (some by dropping the trunk itself but collecting and delivering over much greater distances than they do now), BR have already spent about £330,000 on new road

vehicles to service the first routes. These have been licensed for duty at London and Glasgow to give initial flexibility.

This is first-class equipment, in weight categories seldom explored by the cartage services before. At York Way, for example, BR is now building up a fleet of tractive units comprising 17 Seddons for 30 tons g.t.w., two AEC Mandators for the same weight, five Dodge KP900 and 12 Dodge D310 for 24 tons gross, and one Seddon and four Dodge D308 for 18 tons g.t.w. To go with them are 20 BTC 20 ft. 16-ton semi-trailers, 20 Highway 27 ft. 16-tonners, four BTC 31 ft. 16-tonners, four BTC 32 ft. 21-tonners and 34 Taskers of the same capacity.

At Gushetfaulds, the fleet will be 15 Seddons for 30 tons g.t.w., two Dodge KP900 for 24 tons gross, 11 Seddons for 24 tons gross and five for 18 tons. The matching semi-trailers ordered are 30 Taskers 32 ft. 21-tonners, 18 Scammell 31 ft. 16-tonners, 10 Scammell 20 ft. 16-tonners and eight ETC 20 ft. 16-tonners. All the units have automatic chassis lubrication.

The containers are now coming through in production quantities, these having been put out to 40 firms to tender, of whom 23 submitted examples. New tenders will be put out from time to time, I was assured, but the first contracts were won by Duramin (for the 10 ft.) and British Railways workshops at Derby and Cowlairs (for the 20 ft. and 27 ft.). Following trials with prototypes and comments at the Marylebone open days for hauliers last year, all the containers have recessed edges enabling them to sit between trailer raves which are at least 7 ft. apart. This rules out the need for dunnage—the subject of criticism in this journal at the time.

As well as covered and flat general-goods containers, the former with 7-ft. 8-in.-wide unobstructed end-access, Mr. Jackson is looking at the possibility of meeting the growing demand for bulk units such as pressurized powder tankers. BRS is interested in removals and parcels containers.

The biggest technical problem on the cartage side at the moment is how to accommodate 27 ft. containers if used to the full load rating of 20 tons, because these then gross 22 tons. This is out of the question for any British four-axle artic, and even using the lightest conventional five-axle combination with a Scammell Trunker II tractive unit the maximum legal payload capacity would be around 211 tons. A four-axle layout using an American-style tractive unit like the Kenworth, and wide-spread axles, would probably, fall just short of the 22 tons payload capacity, using a normal semi-trailer, even assuming that individual axle loadings could be met. But the answer seems to be a "skeleton " semi-trailer without boarded platform, such as Northern Ireland Trailers and Ferrymasters use for Lancashire flats.

From one angle, of course, the problem is accentuated by BR's decision to standardize on 28 tons gross for its new artics. What price co-ordination!

In fact, the weight problem is not so critical as it might be. because, as this journal forecast two years ago, the liner train rates will be charged on a per-container basis, not on tonnage. Mr. Jackson was naturally reluctant to quote actual figures for rates, but customers using BR cartage in the trial period have been reporting such figures as £38 door-to-door for a 20 ft. (I5-ton-capacity) container from south London to Glasgow. Other traders have spoken of savings of up to 50 per cent in transport costs by using liner trains.

The trunk rail part of the charge is, of course, a fixed rate but the c. and d. will vary with distance and circumstance. At present, the depots will accept goods (pre-booked) up to one hour before train departure time. Terminals will normally be open from 6 a.m. on Monday to train departure time on Friday, but Saturday morning opening demand at Glasgow has been met, and special arrangements can be made in London if required.

Containers will be given 12 hours free of demurrage from train arrival time—for loading or unloading—or 24 hours if they are reloaded with return traffic. British Railways vehicles can be held free for 15 minutes per capacity ton. After this, demurrage fees will be charged.

What now remains is for the BR Freightliner brochure to come true; it says: "Traders and hauliers operate freely into terminals." Until that happens, the real efficiency and true competitiveness of Richard Jackson's liners must remain slightly shrouded in mystery.