Setting a Standard for Overheads

Page 18

Page 19

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

oNE of the most difficult problems that I myself have to solve is that of convincing hauliers that they must make definite provision for those expenses to which I variously refer as establishment costs," "overhead costs" and business expenses." Hardly less difficult is it to get these men to agree upon what is -a fair percentage of profit, the percentage being calculated on the total expenditure.• Reference to figures will, perhaps, be useful. Take the case of a 7-ton lorry covering an average weekly mileage of 960. Assume that the weekly standing charge is £6 and the running cost per mile is 6d. The total cost of operation per week is thus. £30. What should that vehicle earn if it is to show the operator a reasonable net profit?

Many hauliers believe that anything they receive over and above that £30 is net profit. There are, indeed, some who hold the opinion that some of that £30 is net profit, and quite a few who take less than £30 and, for a time at least, imagine that they are doing good business.

When I ask these men what provision they make for their establishment costs, the usual reply is that they are negligible : which is absurd. A full list of the items of establishment costs would fill this page, but to enumerate them all would serve no useful purpose. A short list is, however, helpful.

Inevitable Expenses. • There are few operators who can escape any of the following expenses :—Telephones, telegrams, postage, bill-headings and envelopes, log sheets, cost of Road and Rail Traffic Act licences, including the expenses of obtaining them, making objections to others and meeting objections, police-court fines and costs, bad debts, legal expenditure and accountants' charges. These are inevitable.

Then there are other expenses, supplementary to the bare operating costs—which are all that are.included in the £30 quoted above. They are not incurred by every haulier, as not every class of business evokes them. I refer to such items as insurance of the load, wages of a second man, lodging allowances, cost of sheets and ropes, provision for storage of goods in transit, and so

el 8 on. This, too, is a short list, capable of almost infinite extension.

The difficulty is that it is almost impossible to quote a universally applicable figure for these costs. It is not even the case that the total rises or falls, as the number of • vehicles operated increases. There always comes a time in the growth of a fleet when the haulier realizes that his overheads, whilst irreducible, are yet excessive in 'relation to the size of his undertaking. He could double his fleet without materially adding to those overheads. On the other hand, some kind of estimate is essential if we are to arrive at a proper basis for rates schedules. In particular branches of the industry, where overheads • are notoriously high or admittedly low, special provision • can be made and rates assessed accordingly. For the general body of hauliers, however, I am firmly of opinion that a percentage addition to vehicle operating costs, calculated to cover establishment costs and to allow for a reasonable net profit, is the best way to arrive at a total .figure for charges, from which rates per mile, per hour, per ton or per ton-mile can be reached.

The Best Method.

There are various methods of arriving at an appropriate percentage. That which I use in the current edition of The Commercial Motor Tables of Operating Costs is, I believe, the best. I recommend it also in the introduction to The Commercial Motor Opetating Costs Record. Previously, I had a more simple method in mind. What it gained in simplicity, however, it lost in practical adaptability.

That method was simply to add 50 per cent, to the vehicle operating costs and thus arrive at the figure for earnings In the-case cited above, for example, in which the vehicle operating cost is shown to be £30, I would have added £15 and have claimed that the minimum revenue per week, for a vehicle of that kind, covering 960 miles per week, should be £45.

arrived at that 50 per cent. by estimating establishment charges as being 25 per cent, of vehicle costs and assuming that net profit should be 20 per cent. of the total expenditure. Thus, if the vehicle costs were £100, I added £25 for overheads. That would bring the total expenditure to £125. Adding 20 per cent. of that sum,

which is £25, for profit, the total earnings should be £150, which is 50 per cent, over and above the vehicle operating cost.

The defect of that method was that it increased the estimated figure for revenue to an excessive amount • when the mileage covered was high. The rates quoted on that basis for big mileages were excessive. In the case of the 7-tonner cited above, the net profit provided for" would be £9. That is an attractive figure, but unattainable in a competitive market.

The present method is to add that 50 per cent, to the vehicle standing charges, but only 25 per cent. to the running costs. A little more calculation is needed to arrive at the figure for revenue, but the result is more in accordance with practice. Actually, the addition to the standing charges covers establishment costs and gives a small margin for contingencies; the addition to the running costs is net profit.

Applying this scheme to the example already quoted, with standing charges of £6 and "running costs of £24, the procedure would be as follows :-26 plus 50 per cent. is £9; £24 plus 25 per cent. is £30: total charge £39, as against £45 by the old method. The gross profit in the one case is £9 and in the other £15. Probably, the net profits are in the neighbourhood of £6 and £12 respectively.

What I mean by stating that the older method was inapplicable to vehicles covering big mileages per week, such as in the case cited, but not so far out when the mileage is comparatively small, can be seen by taking the figure for the same size of vehicle covering 360 miles per week. In that instance, the standing charges would still remain at a total of £6, but the running costs would be only £9. The total vehicle operating cost is thus £15.

A Comparison of Systems.

According to the old method, the minimum revenue would be calculated by adding 50 per cent. to £15. The charge for a week's work would thus be £22 10s., showing a net profit of about £5. By the new method the fair charge would be reckoned as £6 plus 50 per cent., which is £9, in addition to £9 plus 25 per cent., which is £11 5s.; the total is £20 5s. and the net profit approximately £3 15s. There is not, for the lower mileage, so much difference between the two methods.

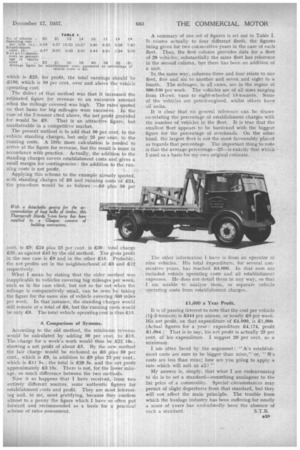

Now it so happens that I have received, from two entirely different sources, some authentic figures for establishment costs and profit. They are most interesting and, to me, most gratifying, because they confirm almost to a penny the figure which I have so often put forward and .recommended as a basis for a practical scheme of rates assessment. A summary of one.set of figures is set out in Table I. It. relates actually to four different fleet& the figures being given for two consecutive years in the case of each fleet. Thus, the first column provides data for a fleet of 20 vehicles; substantially the same fleet has reference in the second column, but there has been an addition of a unit.

In the same way, columns three and four relate to one fleet, five and six to another and seven and eight to a fourth. The mileages, in all cases, are in the region of 500-530 per. week. The vehicles are of all sizes ranging froth 15-cwt. vans to eight-wheeled 15-tonners. Sonic of the vehicles are petrol-engined, whilst others have oil units.

It is clear that no general inference can be drawn co-relating the percentage of establishment charges with the number of vehicles in the fleet. It is true that the smallest fleet appears to be burdened with the biggest figure for the percentage of overheads. On the other hand, the largest fleet is not the most favourably placed as regards that percentage. The important thing to note is that the average percentage-25—is exactly that which I used as a basis for my own original estimate.

£1,000' a Year Profit.

It is of 'passing interest to note that the cost per vehicle (1i-2-tonners) is £444 per annum, or nearly £9 per week.

His net profit, on that expenditure of £4,000, is £1,000. (Actual figures for a year : expenditure £4,174, profit £1,034.). That is to say, his net profit is actually 25 per cent. of his expenditure. I suggest 20 per cent. as a minimum.

I am often faced by the argument : "As establishment costs are sure to be bigger than mine," or, " B's costs are less than mine; how are you going to apply a rate which will suit us all? "

My answer is, simply, that what I am endeavouring to do is to set a standard—something analagous to the list price of a commodity. Special. circumstances may permit of slight departures from that standard, but they will not affect the main principle. The trouble from which the haulage industry has been suffering for nearly a score of years has undoubtedly been the absence of

such a standard. S.T.R.