Stability Depends on Tyre Inflation

Page 40

Page 41

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

The Effects of Insufficient Pressure in the Tyres are Manifold, But Lack of Stability is the Most Marked and the Most

Dangerous

MOST of us talk about "tyre roll " without any definite idea of what it means. We are aware only that it causes a rather uncomfortable sensation which seems to suggest that the vehicle is on the verge of going out of control.

It is well known that an underinflated tyre will cause this roll. Likewise an overloaded vehicle, by causing an excess of tyre deflection, which is tantamount to underinflation, will have the same effect. When a tyre is under-inflated (or overloaded) it is made to deflect to a far greater extent than its designer intended ; it lacks the air support which enables it to assume its normal working shape.

The recommended air pressure is calculated to bring the cover to its proper shape when subjected to its

correct load. If the pressure be decreased, or the load increased, the inadequate air support will result in a distortion of the cross-section of that part of the tyre which is in contact with the ground. This happens even when at a standstill--we have all noticed the " soft " tyre—but its effect is greatly aggravated by external conditions when the vehicle

is in motion. , Under-inflation of front tyres mainly causes heavy steering. This is due partly to the increased area of the tyre-to-road contact which results from excessive deflection, and partly to " grip " caused by tread distortion. Inequality of front tyre pressures will cause a tendency to pull ". and wander, a tendency which has to be corrected with the steering wheel.

Discomfort Caused by Incorrect Inflation.

Most of the uncomfortable sensations and the dagger associated with tyre roll are, however, the result of incorrect inflation of the rear tyres.

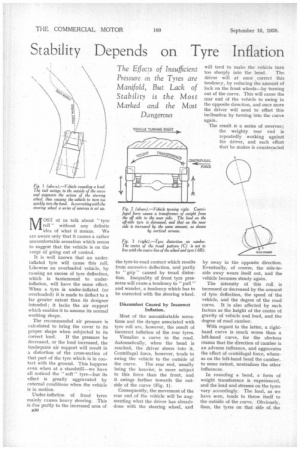

Visualize a curve in the road. Automatically, when the bend is reached, the driver steers into it. Centrifugal force, however, tends to swing the vehicle to the outside of the curve. The rear end, usually being the heavier, is more subject to this force than the front, and it swings farther towards the outside of the curve (Fig. 1).

Consequently, the movement of the rear end of the vehicle will be augmenting what the driver has already done with the steering wheel, and will tend to make the vehicle turn too sharply into the bend. The driver will at once _ correct this tendency, by reducing the amount of lock on the front wheels—by turning out of the curve. This will cause the rear end of the vehicle to swing in the opposite direction, and once more the driver will need to offset this inclination by turning into the curve again.

The result is a series of swerves ; the weighty rear end is repeatedly working against the driver, and each effort that he makes is counteracted by sway in the opposite direction. Eventually, of course, the side-toside sway wears itself out, and the vehicle becomes steady again.

The intensity of this roll is increased or decreased by the amount of tyre deflection, the speed of the vehicle, and the degree of the road curve. It is also affected by such factors as the height of the centre of gravity of vehicle and load, and the degree of road camber.

With regard to the latter, a righthand curve is much worse than a left-hand curve, for the obvious reason that the direction of camber is an adverse influence, and aggravates the effect of centrifugal force, whereas on the left-hand bend the camber. to some extent, neutralizes the other influences.

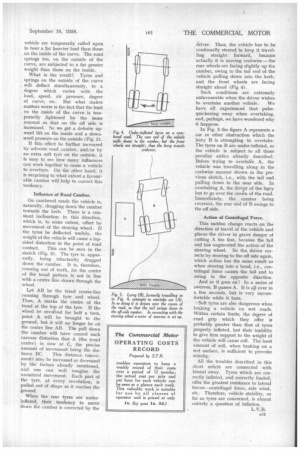

In rounding a bend, a form of weight transference is experienced, and the load and stresses on the tyres vary accordingly. The load, as we have seen, tends to throw itself to the outside of the curve. Obviously, then, the tyres on that side of the vehicle are temporarily called upon to bear a far heavier load than those on the, inside of the curve. The road springs too, on the outside of the curve, are subjected to a far greater weight than those on the inside.

What is the result? Tyres and springs on the outside of the curve will deflect simultaneously, to a degree which varies with the load, speed, air pressure, degree of curve. etc. But what makes matters worse is the fact that the load on the inside of the curve is temporarily lightened by the same amount as that on the off side is increased. So we get a definite upward lift on the inside and a downward pressure on the outside (Fig. 2).

If this effect be further increased by adverse road camber, and/or by an extra soft tyre on the outside, it is easy to see how many influences can work together to cause a vehicle to overturn. On the other hand, it is surprising to what extent a favourable camber will help to correct this tendency.

Influence of Road Camber.

On cambered roads the vehicle is, naturally, dragging down the camber towards the kerb. There is a constant inclination in this direction, which is, to some extent, offset by movement of the steering wheel. If the tyres be deflected unduly, the weight of the vehicle will cause a lopsided distortion at the point of road contact. This can be seen in the sketch (Fig. 3). The tyre is, apparently, being reluctantly.. dragged down the camber. It is, therefore, running out of truth, for the centre of the tread pattern is not in line with a centre line drawn through the wheel.

Let AB be the tread centre-line running through tyre and wheel. Thus, A marks the centre of the tread at the top of the tyre. If the wheel be revolved for half a, turn, • point A will be brought to the ground, but it will no longer be on the centre line AB. The pull down the camber will have caused such carcase distortion that A (the tread centre) is now at C, the precise amount of movement being the dis

tance BC. This distance (movement) may be increased or decreased by the factors already mentioned, and one can well imagine• the unnatural movement. Each part of the tyre, at every revolution, is pulled out of shape as it reaches the ground.

When the rear tyres are underinflated, their tendency to move down the camber is corrected by the driver. Thus, the vehicle has to be continually steered to keep it travelling straight forward, because actually it is moving crabwise— the rear wheels are facing slightly up the camber, owing to the tail end of the vehicle pulling down into the kerb, and the front wheels are facing straight ahead (Fig 4).

Such conditions are extremely unfavourable when the driver wishes to overtake another vehiele. We have all experienced that pulsequickening sway when overtaking, and, perhaps, we have wondered why it happens.

In Fig. 5 the figure A represents a car or other obstruction which the lorry B is attempting to overtake. The tyres on B are under-inflated, so the vehicle is subject to all those peculiar antics already described. Before trying to overtali-e A, the vehicle was travelling along in the crabwise manner shown in the previous sketch, i.e., with the tail end pulling down to the near side. In overtaking A, the driver of the lorry has to go over the crown of the road. Immediately, the camber being ieversed, the rear end of B swings to the off side.

Action of Centrifugal Force.

This sudden change reacts on the direction of travel of the vehicle and places the driver in grave danger of cutting A too fine, because the tail end has augmented the action of the steering wheel. So the driver corrects by steering to the off side again, which action has the same result as when steering into a bend, i.e., centrifugal force causes the tail end to swing in the opposite direction.

And so it goes on ! In a series of swerves, B passes A. It is all over in a few seconds, but is very uncomfortable while it lasts.

Soft tyres are also dangerous when braking a vehicle on wet roads. Within certain limits, the &pee of road grip which they offer is probably greater than that of tyres properly inflated, but their inability to give firm support to the weight of the vehicle will cause roll. The least amount of roll, when braking on a wet surface, is sufficient to provoke sideslip.

All the troubles described in this short article are connected with lateral sway. Tyres which are correctly inflated, and correctly loaded, offer the greatest resistance to lateral forces—centrifugal force, side wind, etc. Therefore, vehicle stability, so far as tyres are concerned, is almost entirely a question of inflation.

L.V.B.