The POWER and COMFORT of

Page 58

Page 59

Page 60

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

A MODERN MOTOR

AMBULANCE

Road Test No. 41

The Latest Du Cros Sixcylinder Ambulance is Included in Our Series of Road Tests

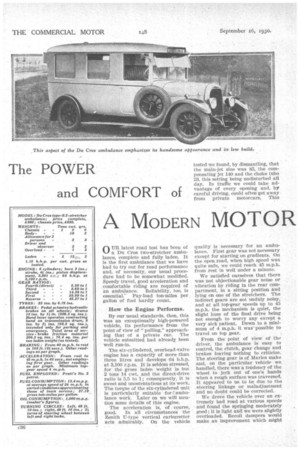

OUR latest road test has been of a Du Cros two-stretcher ambulance, complete and fully laden. It is the first ambulance that we have had to try out for road performance and, of necessity, our usual procedure had to be somewhat modified. Speedy travel, good acceleration and comfortable riding are required of

an ambulance. Reliability, too, is essential.' Pay-load ton-miles per gallon of fuel hardly count.

How the Engine Performs.

By our usual standards, then, this was an exceptionally high-powered vehicle, its performance from the point of view of " pulling," approaching that of a private car. The vehicle submitted had already been well run-in.

The six-cylinclered, overhead-valve engine has a capacitY of more than three litres and develops 64 b.h.p. at 3,100 r.p.m. It is seldom stressed, for the gross laden weight is but 2 tons 14 cwt. and the direct,drive ratio is 5.5 to 1; consequently, it is sweet and unostentatious at its work. The torque of the six-cylindered unit is particularly suitable for,: ambulance work. Later on we will mention some details of this engine.

The acceleration is, of course, good. In all circumstances the Zenith U-type vertical carburetter acts admirably. On the vehicle

tested we found, by dismantling, that the main-jet size was 85, the compensating jet 140 and the choke tube 23, this setting being undisturbed all day. In traffic we could take advantage of every opening and, by careful driving, could often get away from private motorcars. This

quality is necessary for an ambulance. First gear was not necessary except for starting on gradients. On the open road, when high speed was quite safe, we could reach 45 m.p.h. from rest in well under a minute.

We satisfied ourselves that there was not objectionable gear noise or vibration by riding in the rear compartment, in a sitting position and lying on one of the stretchers. The indirect gears are not unduly noisy, and at all top-gear speeds up to 45 m.p.h. the mechanism is quiet, the slight hum of the final drive being not enough to worry any except a very sick patient. Down to a minimum of 4 m.p.h. it was-possible to travel on top gear.

From the point of view of the driver, the ambulance is easy to control, the clutch, gear change and brakes leaving nothing to criticize. The steering gear is of Merles make and, on the particular vehicle we handled, there was a tendency of the wheel to jerk out of one's hands when a rough surface was traversed. It appeared to us to be clue to the steering linkage or maladjustment and no doubt could be corrected.

We drove the vehicle over an extremely bad road at various speeds and found the springing moderately good ; it is light an we were slightly overloaded. Recoil dampers would make an improvement which might he worth while. With springs of this type arid a body over 7 ft. in overall height, one naturally avoided cornering at speed, not that this would be ordinarily necessary.

The power found so useful on the level is even more valuable on hills. We climbed Brockley Hill, on the Elstree-Edgware road, Middlesex, in a southward direction, from rest in 55 seconds. The climb is 600 yds. long from the starting point which we now use, the gradient averaging 1 in 17i. In 20 seconds we were in third gear, and we accelerated thus to 27 m.p.h., changing to top gear seven seconds before reaching the crest ; our speed averaged 23 m.p.h.

The same hill, climbed from the south, gives an ascent 440 yds. long with an average gradient of 1 in 11. Second gear sufficed for most of the way, yielding a speed up to 20 m.p.h., and third gear was engaged near the top, the time being 47 seconds and the speed ;18 m.p.h., which is tothmendable. Continuing down the other side and passing the cross-roads at 20 m.p.h., we accelerated to 38 m.p.h. before facing the climb into Elstree, and reached the village in top gear at 27 m.p.h.

The Final We then tried the ambulance on Cocks Hill, a short, steep climb on the Elstree-Barnet road. It is 200 yds. long and has an average gradient of 1 in 8.57, increasing near the crest toil in 6. This we climbed in second gear, accelerating to 20 m.p.h. and dropping to 18 m.p.h. on the 1-in-6 section. Our time was 29 seconds and our average speed 14.1 gi.p.h. These three timed ascents suffice to indicate the performance on hills, which is surprisingly good. There was no sign whatever of engine overheating.

Either the hand-operated transmission brake or the hydraulic fourwheel brakes would easily hold the vehicle on a 1-in-6 incline.

We tested braking performance on the level, and our graph gives the readings. obtained. The qualities of the hydraulic system of brake. actuation are familiar to our readers and we need not, therefore, stress the Posy and well-balanced' operation. The action was found to be progressive and the efficiency comparatively good.

Our Fuel-consumption Tests.

Fuel consumption is not the most important consideration of an ambulance, although with fleet operators like the Metropolitan Asylums Board it must claim careful atten tion. On four separate tests we obtained 14.4, 13.6, 13.2 and 12.4 miles per gallon, using Pratt's No. 3 spirit. The best reading was at an average speed of 24 m.p.h. on a nearly level main road with no traffic obstacles. The worst included a half-mile climb at a gradient of about 1 in SO and a halfmile of traffic negotiation in a tortuous country town. On a long run 14 m.p.g. or'15 m.p.g. might easily be obtained with this carburetter setting. It must be remembered that we had a load equal to a driver and stretcher-bearer, a nurse and two patients, plus an overload of 11 cwt.

We found the speed readings of the speedometer inaccurate on a sliding scale up to 5 per cent. and corrections have had to be made in respect of all the graphs and other

speed results given in this article. The inaccuracy was probably due to irregular inflation of the lowpressure tyres.

Some General Dimensions.

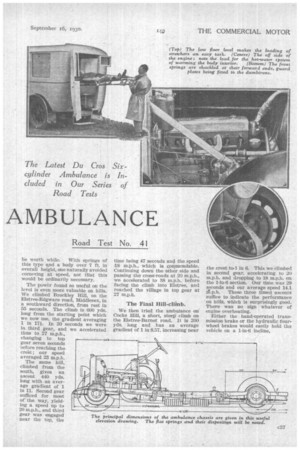

Out in the country we halted to consider some of the constructional features of the Du. Cros'ambulance. The wheelbase is 11 ft. 9 ins, and the frame overhang 2 ft. 41 ins., the front and rear track being 5 ft. With cab dimensions giving a rather upright position for the driver, a rear compartment is obtained measuring, internally, 7 ft. 81 ins. long, 5 ft. 4 ins wide and 5 ft. 41 ins, high to the roof bearers. One stretcher platform, 6 ft. long and 1 ft. 101 ins. wide, is fixed at each side of an 18-in. gangway and either may be used for six sitting patients.

c38

Folding steps at the rear afford easy entrance, their heights being 8 ins. and 1 ft. 31 ins., whilst the floor height is only 1 ft. 101 ins., except where gently arched over the axle. The stretcher platforms are only 3 ft. 2 ins, above the ground level, and loading is not difficult.

The frame height is about 1 .ft. 8 ins., the frame being level, except for the rear-axle arch. The low floor is obtained by off-setting the engine and

transmission. The engine-gearbox unit is carried in three-point sus pension, the front support incorporating a big rubber bush of about 9 ins. external and 31 ins, internal diameter, and each rear support two large rubber cones, 'point to point, with the bolt passing vertically through their axis. The object has been to insulate the frame from engine vibration and it has succeeded in a creditable measure.

From the brake drum behind the gearbox an exposed tubular shaft with two Hardy Spicer joints takes the drive to the underslung worm and wheel, the differential case coming conveniently beneath the near-side stretcher. The axle shafts are semi-floating,' the flat laminated springs being underslung and mounted directly beneath the frame members. They take the torque and

drive. The front springs are mounted above the axle and shackled at their front ends.

A good point is the quick access afforded to the spare wheel, which is carried on a bracket that swings outward as the door is opened. Six nuts hold each road wheel and the jack positions under the axles are not troublesome to reach.

Warming the Interior.

A hot-water take-off is provided to warm the patients' compartment, over-cooling of the engine being guarded against by a thermostat. Otherwise the engine is of orthodox design with pump circulation of water and oil, pressure-lubricated valve-rocker bearings, easily detached oil filter, a neat gland adjustment for the water impeller, automatic and hand advance of the Simms magneto, 12-volt dynamo and enclosed starter pinion. The gearbox has two detachable plates, and a mechanical tyre pump could be fitted. The single-plate dry clutch has a steel driven disc with friction fabric on the flywheel and outer plate, the effective diameter being 12 ins, and the friction area about 561 sq. ins, each side. Tension on the 12 springs is adjusted by fine-thread screws, the nuts on which form the abutment for the three clutch-operating levers.

Concluding, the standard equipment may be enumerated. Two rigid stretchers, with either pneumatic or sponge-rubber beds, are provided, also a seat cushion (in two parts) to take the place of one stretcher, one M.A.B.-type carrying obair, an attendant's seat, which is slung between the stretchers, and a full kit of tools.

The ambulance has been evolved from a long experience and study of the requirements and it is a fast, comfortable and efficient outfit.