TORQUEING ABOUT A REVOLUTION

Page 132

Page 133

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

The lost wheel syndrome is one of the great transport mysteries. To find out what could be done to cure it, the Institute of Road Transport Engineers commissioned tests by the Motor Industry Research Association and has just unveiled its findings.

• With today's design and specification of wheelstuds in hubs, studs sometimes break or wheels sometimes come loose at the recommended tightening torques.

Last month the consolidated report on the research commissioned by the Insti tute of Road Transport Engineers began to thud on desks in high places. Its main conclusions fit on one page. Two of them .state that the detail design of studs needs to be revised, and that wheelnuts should be tightened more in the first place.

Present specifications of wheel studs do not provide enough margin to stay intact when there are tiny defects or loss of tension to contain the imposed loads within the clamped joint.

The problem, it seems, is fatigue. It was diagnosed as the cause of every stud failure examined. Fractures occurred mostly where there was high stress concentration, or where there was surface roughness or a surface crack invisible to the naked eye. Both those conditions often coincided at that part of the thread just inside the base of the nut.

Therefore, reasons the IRTE, the stresses in the threads entering the nut need to be less and the surface finish needs to be better — and preferably put in compressive pre-stress by rolling to inhibit crack spreading. Some useful evening-out of the thread stresses would be achieved by incorporating a gradual run-out of the threads on the studs and in the nuts. In practiced terms that means a gentle waisting of the stud-shank behind the thread and a tapering entry on nuts.

The IRTE would like studs to have 24mm diameter (presently 22mm) threads to give enough reserve to avoid fatigue failures if there should be some small deficiency.

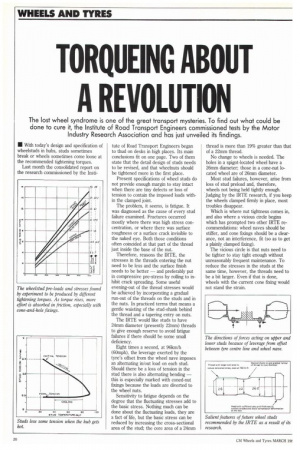

Eight times a second, at 96km/h (60mph), the leverage exerted by the tyre's offset from the wheel nave imposes an alternating in/out load on each stud. Should there be a loss of tension in the stud there is also alternating bending — this is especially marked with coned-nut fixings because the loads are diverted to the wheel nuts.

Sensitivity to fatigue depends on the degree that the fluctuating stresses add to the basic stress. Nothing much can be done about the fluctuating loads, they are a fact of life, but the basic stress can be reduced by increasing the cross-sectional area of the stud; the core area of a 24mm thread is more than 19% greater than that of a 22mm thread.

No change to wheels is needed. The holes in a spigot-located wheel have a 26mm diameter; those in a cone-nut located wheel are of 26mm diameter.

Most stud failures, however, arise from loss of stud preload and, therefore, wheels not being held tightly enough. Judging by the IRTE research, if you keep the wheels clamped firmly in place, most troubles disappear.

Which is where nut tightness comes in, and also where a vicious circle begins which has prompted two other IRTE recommendations: wheel naves should be stiffer, and cone fixings should be a clearance, not an interference, fit (so as to get a plainly, clamped fixing).

The vicious circle is that nuts need to be tighter to stay tight enough without unreasonably frequent maintenance. To reduce the stresses in the studs at the same time, however, the threads need to be a bit larger. Even if that is done, wheels with the current cone fixing would not stand the strain. Nut tightness is therefore limited at present by the strength and stiffness of the components. Hence the modest changes to detail design recommended.

In the meantime, the IRTE suggests raising tightening torques as much as possible within the capabilities of existing wheel assemblies: 700Nm (5001bft) if applying oil, and 800Nm (6001bft) if not.

Hole distortion in cone-fixed wheels is a problem. Tests done by the Motor Industry Research Association gave limiting ranges of tightening torque of 1,0801,360Nm dry, 800-950Nm with oiled threads, and 700-800Nm if the seats and threads are oiled.

The IRTE felt that, if it could establish a single all-purpose tightening torque, it could clear away the confusion of varying advice that surrounds wheel-fixing procedure. After all considerations the base, common-denominator, torque selection was 800Nm (600Ibft) unlubricated.

At this, alarm bells clanged in the manufacturers camps. Wisely, however, after an opening barrage of slings and arrows labelled "dangerous", "impractical" and "irresponsible", the arguments have subsided. One of the more reasonable points now being made is that Continental DIN-standard fastenings with hemispherical washers might pack more hole distortion power than coned nuts. Such fastenings were not included in the research programme done by MIRA. Extra test work now seems inevitable, because the Department of Trade and Industry (which helped to fund the IRTE research) and the Department of Transport have now charged the British Standards Institution with development of a revised wheel-fixing standard.

Meanwhile, the IRTE is still quietly collecting evidence in the search for the conclusive truth. A massive long-term trial is underway to assess the performance of wheels tightened to 800Nm unlubricated. To date, more than 9,000 trucks and trailers, with all types of disc-wheel fixing, are being monitored at the rationalised torque figure. More fleets are continually joining the IRTE trial.

The whole objective — and it is still not known whether it will br achieveable, is to see whether wheels might, once fitted, never need the frequent checks that are at present deemed essential.

One of the important revelations of the research is that slackness develops in wheel fixings without the nuts unscrewing. They do not rotate at all in the early stages, but later they do unscrew, by which time the torque will have dropped below some 136Nm (100Ibft).

The immediate implication is that methods of stopping nuts rotating, such as clips, tab washers, adhesive or selflocking nuts, have merely "last resort" value. The same applies to the virtue of handed threads. That "last resort" func tion deserves respect, but it does not prevent the development of tension-loss that lies behind most fatigue failures. Nutlocking, therefore, does not remove the need for retorquing.

Neither is tension loss just a matter of careless fitment, it seems. The MIRA tests revealed that there is some loss of tension within quarter of an hour of wheel fitment — without the wheel even turning or carrying any load. The effect is much worse with cone fixings than with clamped ones with spigot location. Settlement is vastly reduced, however, at 800Nm.

Once working the fixings suffer further settlement. Again, though, the general pattern is that the consequent loss of preload in the fastening is less if the original tightening torque is high enough in the first place.

Further circumstances develop to whittle away the preloads. The wheel naves flex, and the thinner they are the more they distort. The flexing induces microscopic wear and fretting. Then comes heat soak from the tyres and from braking. There was up to 6% loss of preload in the MIRA tests, even at 90°C.

If the initial tightening torque is not great enough, the relaxation of tension can cause wear and settlement to accelerate, eventually causing looseness severe enough to cause the nuts to unscrew, quite apart from the risk of stud failures.

All these observations have been with clean metallic surfaces. Paint on the clamped surfaces makes the settlement more rapid; frequent tightening then becomes inevitable. Some practical conflict arises here, as paint helps to stop corrosion. Perhaps a thin, sprayed coating of primer, evenly applied could be used.

There will very likely be several contentious details in the ITRE volume of research reports worthy of erudite argument. But the overall lession seems .bound to remain intact: that the prime solution to wheel insecurity is nut tightness — and that more peace of mind follows from greater tightening torques.