Brazil ---where road transport is king

Page 50

Page 51

Page 52

Page 53

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

but hauliers are having a little trouble in getting the crown to fit

Part one of a report by the Editor on a visit to South America

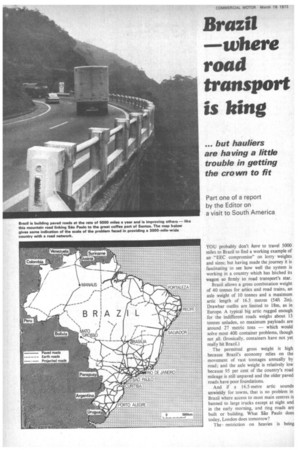

YOU probably don't have to travel 5000 miles to Brazil to find a working example of

an "EEC compromise" on lorry weights and sizes; but having made the journey it is fascinating to see how well the system is working in a country which has hitched its wagon so firmly to road transport's star. Brazil allows a gross combination weight of 40 tonnes for artics and road trains, an axle weight of 10 tonnes and a maximum artic length of 16.5 metres (54ft 21n). Drawbar outfits are limited to 18m, as in Europe. A typical big artic rugged enough for the indifferent roads weighs about 13 tonnes unladen, so maximum payloads are around 27 metric tons — which would solve most 40ft container problems, though not all. (Ironically, containers have not yet really hit Brazil.) The permitted gross weight is high because Brazil's economy relies on the movement of vast tonnages annually by road; and the axle weight is relatively low because 95 per cent of the country's road mileage is still unpaved and the older paved roads have poor foundations. And if a 16.5-metre artic sounds unwieldy for towns, that is no problem in Brazil where access to most main centres is banned to large trucks except at night and in the early morning, and ring roads are built or building. What Sao Paulo does today, London does tomorrow? The restriction on heavies is being matched by the building of urban freight terminals, and cheap land and labour make these reasonably economic.

Free-for-all On many fronts — industry, economics, finance and, not least, transport Brazil is one of the most fascinating countries in the world for a European to visit today. I went there in February as the only British transport journal editor on a study tour organized by Saab-Scania for a party of 20 European industrial, financial and transport journalists, and including representatives from the Dutch and Swedish road haulage associations.

Road transport in Brazil presents a stimulating but confused picture — mainly because it is trying to evolve very quickly from a pioneering state into a sophisticated and organized industry to meet the demands of the country's mushrooming expansion.

Haulage is an unlicensed free-for-all reminiscent of the Twenties, yet rates are controlled; most trucks have gaily hand-decorated wooden bodies, but refinements like power steering are commonplace; one sees tachographs fitted, but they are seldom used; there are no legal limits on lorry drivers' hours, yet safety belts are compulsory on new trucks and the law (vainly!) demands their use; fire extinguishers are obligatory on commercial vehicles, yet one sees wiring looped amateurishly around spirit tankers.

The list of apparent contradictions is almost endless, but the most important basic fact is that this huge country is in the midst of the biggest roadbuilding programme ever undertaken in the world, and has committed itself as a matter of policy to road transport. Over 20km of road are being surfaced every day and 5000 miles of paved roads will be built this year alone. With World Bank help, Brazil is spending over £200m on paving roads in 1973-4 and the federal roadbuilding programme for 1973 is over £.400m.

Tremendous growth By far the biggest item in the country's national budget is transport — four times the amount devoted to education, and double the Army expenditure. The implications for road haulage are clear, both in the budget and in the fact that the country's foreign trade has quadrupled in nine years and the gross national product is growing by 10 to 12 per cent per annum.

Coping with this expansion is the problem. Typical trunk hauls, over still-indifferent roads, can be 2500 miles in one direction and drivers may be away from base for a month at a time. There are over 200,000 owner-drivers or small hauliers, many of whom tramp around the country in the wake of the main crops — coffee, tea, bananas and so on — for whatever rates they can get and then fight their way over the mountain roads to the trade ports such as Santos and Porto Alegre. In Brazil's climate they can live in or under the truck for days waiting for a worthwhile load; sleeping in the cab is common and a hammock under the trailer is a popular alternative.

Small wonder that the Brazilian road haulage association asserts that the country's rates per ton-mile are the lowest in the world.

The same association, admitting only properly established hauliers, reveals what organization can do: its 300 members carry 78 per cent of the total road tonnage.

But Brazilian haulage is familiarly fragmented and some parts of the industrial boom are hamstrung for lack of proper transport. I heard of steel companies paying double rates to ensure quick turn-round and the exclusive use of trucks carrying constructional steel to sites. Heavy hauliers simply can't finance new truck purchases fast enough to meet the transport demand. Credit finance costs 35 to 45 per cent per annum on the open market and the effect is so serious that the Government is backing a special loan fund charging 30 per cent interest over three years solely for the purchase of trucks exceeding 30 tons gross weight.

Apart from one or two bulk freight routes the railways offer little competition, being reputedly slow and unreliable (like the telephone and postal services). Coastal shipping, which could have lived fatly off Brazil's enormous coastline and ample ports, is only just emerging from a long decline ascribed to pilferage, labour disputes and outdated equipment.

Invading the jungle A lot of the roadbuilding has a social purpose -especially the 2500-mile highway being bulldozed through the remote northern tropical jungle of Amazonas. This state comprises two-thirds of Brazil's land area but has only 8 per cent of the population and the main purpose of the road is to open up the Amazon jungle for colonization by the unemployed of the north-eastern states.

This is part of a "national integration" programme -which will become international when the Transamazonica Highway runs its full 3750 miles to Lima, in Peru, linking Atlantic to Pacific.

The director-general of Brazil's National Department of Roads and Highways (DER) put the national "infrastructure policy" to me in a nutshell: To open up new areas with unpaved "pioneer" roads; then to pave them when cost /benefit analyses show that traffic has increased to a justifiable level; third, to put in railways only where concentrated flows of bulk traffic are likely to be long-term, such as in carrying mineral products.

Already — with a ring familiar to European ears — the World Bank is questioning Brazil's overwhelming choice of roads at the expense of railways. Whatever second thoughts there may be now, nothing will alter the fact that Brazil will have increased her mileage of surfaced roads from 12,000km in 1960 to 53,400 in 1971 and 71,000km by next year — an extraordinary achievement for a country of only 100m people. It is no surprise that the Brazilian roadbuilding force totals a million people. There are about 44-m vehicles in the country, but from next year they'll be rising at about 1m a year. , Perhaps the most difficult thing to grasp about Brazil is its size. A day's hard travel turns out, when traced that evening on the map, to be a derisory 300 miles. The country is nearly 3000 miles wide and deep; superimpose it on Europe and it would stretch from the southern tip of Greece to beyond the north of Scandinavia, blanketing Europe, including much of Western Russia.

It exists on road transport — carrying raw materials and tropical fruits from the North, minerals and dairy products from the north-east and centre, manufactured products from the great eastern industrial belt, and vegetables, meat, fish and lighter industrial materials from the fertile south — the euphonious Rio Grande do Sul.

Industry is concentrated on Sao Paulo, a vast, sprawling, skyscraper city of over seven million people about 300 miles southwest from Rio de Janiero.

Meeting the hauliers It was in Sao Paulo that we met the president of Brazil's road haulage association — Associacao Nacional das Empresas de Transportes Rodoviarios de Carga (NTC) — Mr Denisar Arneiro, who is an IRU vice-president this year too. Some of his senior members had flown in from hundreds of miles away to discuss South American haulage with our party, and the NTC's chief engineer was able to act as interpreter he is Leo Curtis, MIRTE, who served with Bouts Tillotson for some years, and first went to Brazil as a consultant to set up a service network for AEC there.

Mr Arneiro is understandably pleased that road transport in Brazil is now getting such tremendous Government backing, if only because it justifies the, faith of the haulage pioneers who, from 1929 to as late as 1950, had to struggle over unmade roads through raw, often dangerous country.

He also explained shrewdly that the railway network (built largely by the British) had been constructed to suit foreign investors — to extract raw materials and introduce manufactured imports through the east coast ports. So the lines nearly all run on unconnected east-west routes between port and hinterland, and are now uselessly orientated for the mainly north-south traffic flows.

Mr Arneiro runs 92 trucks — 72 of them Scanias — on steel traffic and general goods and, like most of his members, subcontracts a lot of tonnage to owner-drivers and small operators who are regarded as an integral part of the industry. It is the free-ranging "non-contract" owner-drivers whose activities the NTC is pressing the Government to, curb, on the grounds that they are operating irresponsibly, with no technical or commercial expertise and are endangering established hauliers by cutting rates as much as 30 per cent. A familiar plea!

We were assured that any operator running an organized business could join NTC, however small his fleet. Vetting applicants is not made easier by the fact that, in the absence of any licensing system, anyone can simply register himself as a transporter and start business. We gathered that the one-man-with-a-telephone clearing house was the type of operator really regarded as beyond the pale. Most NTC members operate extensive clearing houses for their "approved" contract hauliers.

Total liability for hauliers One reason why NTC members have

such a lion's share of Brazil's roP-, is that their status is recognized nut only by government and by state authorities but by the big industries, many of whom are associate NTC members. Under Brazilian law a carrier is totally liable for the full value of the goods he carries, an obligation which the owner-driver sometimes cannot meet. (We were also told of a growing business in "disappearing" loads, suggesting a well-organized crime campaign.

The NTC's conditions of carriage cannot reduce this total in-transit obligation, but the association's members are allowed by law to charge the customer 0.02 per cent of the freight's value for each Brazilian state the goods pass through. This money is a premium for a national in-transit insurance fund and, since the customer pays directly for the cover on his own goods, he gets prompt and undisputed settlement of claims.

For the system to work, freight value has to be shown on the carriage documents; but this is only a small addition to the bureaucratic function which transport documents perform in Brazil. For instance, it is essential for the freight rate for each consignment to be shown on the consignment note because the Government deducts 3 per cent of the rate at source as a special income — or revenue — tax. There is also an industrial goods tax levied on an ad valorem basis.

And all this is not left to chance: there are "fiscal posts" on the main highways, at which drivers must present their consignment documents for checking and stamping.. And if a driver arrives at his destination without the proper fiscal stamp on his consignment note the consignee will almost certainly refuse the load.

Customers pay the fees !

Such elaborate controls have bred an equally extensive defence mechanism. The NTC publishes carefully costed rates per hour for demurrage, according to vehicle and body type; hauliers are being encouraged to cost their operations minutely — and now the Government has given legal backing to the NTC members — and they alone — charging customers 20 centavos (about 2p) per consignment note towards NTC association funds. The 20 cents is payable whether the consignment note refers to a 101b parcel or a 10-ton load.

The haulier bulks these monies up and pays them into the NTC monthly — so customers are paying the hauliers' membership fees!

Leo Curtis told me that a 40-tonne-gvw artic running about 4000 miles a month would have a total operating "cost", including overheads and profit, of only 9 centavos /ton-km, which is less than 2p a On the heavily freighted 400km route from Curitiba to Sao Paulo the official haulage rate varies from less than lp per ton-mile to about 3p /ton-mile according to consignment size and value.

Revenue is limited for many hauliers because on dirt roads in the rainy season they can load trucks to only two-thirds of rated capacity.

Legal loading is one of the points on which the Brazilian authorities are sharp. They have weighbridges on the most heavily used truck routes — but they commonly regard overloading up to 1+ tonnes as an allowable tolerance, and though the fines for heavier infringements are based on the severity of the overloading they're still less than the extra profit.

A peculiar feature of Brazilian tax is that trucks pay an amount according to their maximum load capacity — but each vehicle pays the tax applicable in its year of registration. Since taxes keep rising like other things (national inflation was down to 12 per cent last year, compared with frightening annual figures of between 90 per cent and 140 per cent in the early Sixties) an old truck pays less tax than its identical, but new, twin.

The NTC "enjoys" published rates — a two-edged sword. Over its 10 years existence the association, through its

representatives in 100 towns and 24 regions, organized as a federation of state haulage syndicates, built up a rates system, which was published. Now, while the rates have no Government backing, there is implied official blessing for any increases the NTC can get (annually or more often) after presenting a most detailed case to the Price Control commission.

This is obviously useful in negotiations with customers, but the increases are percentage increments on rates which may never have been adequate in the first place, though now hallowed by usage. Also, as NTC members have found to their irritation, publishing the most detailed rates schedules provides the rates-cutters with their own ready-reckoner. NTC rates are based on eight classifications of traffic according to weight /volume, with a base of 300kg /sq metre. Scales B to G are then approximately 10 per cent higher for each successively less dense class of freight (lead travels cheaply, feathers expensively); and a top Scale H is for special traffics, such as high-value or fragile loads, by negotiation.

Losing the rates battle by inches

When the association goes to the price commission for a rates increase it has to present a most detailed case, showing not only the average of price rises throughout Brazil for any particular basic commodity such as fuel, but the exact calculation of the effect of this on a range of typical haulage vehicles running certain average mileages.

Despite detailed submissions running to perhaps 10 pages of foolscap for a single increase the Price Control Commission seldom grants anything like the full amount. I was shown a submission for 18 per cent, on which about 12 per cent had been allowed.

Presented to the customer, it is paid without question and passed straight on; all Brazil operates on official price levels and increments. But as each permitted rates increase falls short of the actual cost increase, hauliers are in the frustrating situation of seeing their small profits slipping away in the midst of a road transport boom.