MACHINE

Page 52

Page 53

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

11000LS

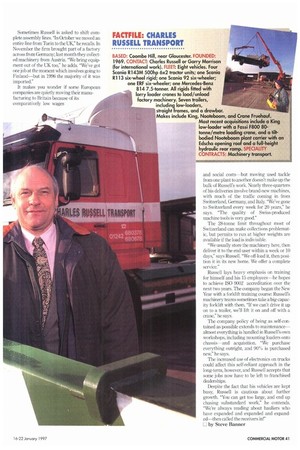

Hauling factory machinery is a niche not overcrowded with competitors but, as Gloucestershire operator Charles Russell has found, it does require a significant investment in lorry loaders to do the job properly.

Identifying a niche and filling it is one route to profitability in a ruinously competitive industry. And it's a route that Charles Russell Transport is pursuing with a vengeance. Based at Coombe Hill, not far from Gloucester, the family-owned company specialises in delivering factory machinery using a small fleet of self-loading vehicles.

Its latest acquisition is the UK's first Italian-built Fassi F800 80t/m loader, mounted on a specially constructed King trailer and capable of lifting a 20-tonne piece of assembly-line equipment (CM 5-11 December 1996).

Charles Russell himself has a farming background. He started hauling agricultural products and livestock, and edged into the machinery sector in the early 1970s when he began buying and selling second-hand farm equipment. To make deliveries he acquired what he believes was the first Hiab lorry loader in Gloucestershire.

Geiting started

His reputation. and news of the then-novel Hiab, spread; in late 1973 he took on some third-party UK-wide industrial machinery delivery work for a local firm. By 1975 he vras being asked to deliver into Europe.

"In those days you had to have permits so I bought a little company which had a dozen or so," he recalls. His Continental service runs under the Charles Russell International banner, and he's still working for many of the customers who employed him 21 years ago.

The business is based in a clutch of attractively-converted farm buildings on a 90-acre site. "Although transport is our main source of income, we still do a little farming," he says. "As well as factory machinery we handle refrigeration equipment which goes into all sorts of places, including big dairies and supermarkets. On one occasion we had to hire a helicopter to put a refrigeration unit onto the roof of a building."

The fleet is dominated by Scanias. "I've run them for years," he says. "The drivers like them, the back-up in both the UK and Europe is very good, and residual values are strong."

Russell operates four R143M 500hp 6x2 Scania tractors, including two left-hookers. All that power helps offset some of the impact that speed limiters have had on overall journey times. They average 7.758.75mpg on Continental work.

Though mightily impressed with 3 Series Scanias he won't be acquiring one of the new 4 Series just yet, preferring to let other operators discover and iron out any teething troubles before he parts with his cash.

"We're just in the process of acquiring our first 6x9 tractor unit," he says. "That order will be placed between now and March, and I've got a Volvo HI on the shortlist at the moment. The FH has been on sale for a while now and its teething problems have been pretty much sorted out."

So why does he need a 6x4? "At the start of this year we began running under the Special Types regulation—STGO 2—and I feel that using a 6x4 with the King trailer will give me that bit better traction," he explains, " especially when there's snow on the ground."

His rigid fleet includes a trio of six wheelers: a 380hp Scania R113, a Scania 92, and a lonely F:RF with a 290hp Cummins L10 engine. They're supported by a MercedesBenz 819 7.5-tonner. The bigger rigids are all drawbars. Two are kitted out with 31t/m PM loaders; the Scania 92 has a 28t/m loader, also from PM. All three are rear-mounted. The 7.5tonner is fitted with a Palfinger loader, but it's being re-equipped with a 5t/m Fassi.

The 814 is driven by Charles' son Ben. Oliver, his older brother, drives one of the artics, and Charles' wife Anne is a director. Garry Morrison runs the international side.

"When we arrive the crane arrives," says Russell. "Everything is done in-house, and this eliminates uncertainty. What's more, we have roller-type skates and even air-skates so we can move other machinery within a factory to get access to the machine we need to shift." All the rigids are fitted with automatic chassis lubrication, which also services the loader cranes. "The King + trailer is equipped with it too, but because the

Fassi loader is a continuously-slewing one it has a separate lubrication system," says Russell. "It's cost a lot of money, but should keep down repair costs."

Despite his policy of retaining work inhouse wherever possible, Russell does bring in the odd subcontractors' crane when extra lifting capacity or (more usually) extra reach are required. "My crane bill last year was in the region of L50,000," he says.

Moving into Britain

No plant manager wants machinery movements to disrupt output: about a third of Russell's collection and delivery work is outside normal working hours. Sometimes Russell is asked to shift complete assembly lines. "In October we moved an entire line from Turin to the UK," he recalls. In November the firm brought part of a factory across from Germany; last month they collected machinery from Austria. "We bring equipment out of the UK too," he adds. "We've got one job at the moment which involves going to Finland—but in 1996 the majority of it was imported."

It makes you wonder if some European companies are quietly moving their manufacturing to Britain because of its comparatively low wages and social costs but moving used tackle from one plant to another doesn't make up the bulk of Russell's work. Nearly three-quarters of his deliveries involve brand-new machines, with much of the traffic coming in from Switzerland, Germany, and Italy. "We've gone to Switzerland every week for 20 years," he says. "The quality of Swiss-produced machine tools is very good."

The 28-tonne limit throughout most of Switzerland can make collections problematic, but permits to run at higher weights are available if the load is indivisible.

"We usually store the machinery here, then deliver it to the end-user within a week or 10 days," says Russell. "We off-load it, then position it in its new home. We offer a complete service."

Russell lays heavy emphasis on training for himself and his 15 employees—he hopes to achieve ISO 9002 accreditation over the next two years. The company began the New Year with a forklift training course: Russell's machinery teams sometimes take a big-capacity forklift with them. "If we can't drive it up on to a trailer, we'll lift it on and off with a crane," he says.

The company policy of being as self-contained as possible extends to maintenance almost everything is handled in Russell's own workshops, including mounting loaders onto chassis—and acquisition. "We purchase everything outright, and 90% is purchased new," he says.

The increased use of electronics on trucks could affect this self-reliant approach in the long-term, however, and Russell accepts that some jobs now have to be left to franchised dealerships_ Despite the fact that his vehicles are kept busy, Russell is cautious about further growth. "You can get too large, and end up chasing substandard work," he contends. "We're always reading about hauliers who have expanded and expanded and expanded—then called the receivers in!"

LC by Steve Banner