D

Page 50

Page 51

Page 52

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

' URING the quarter of a century or more which has been occupied by theWevelopment of the modern motor vehiclefpractically all the major components have evolved to a surprising extent, departing not only in detail but, to some extent, in principle from the rudimentary ideas which characterized the first models.

In one respect, however, this is nott the case, for although, to all appearances, the modern gearbox is far removed from its prototype, the general working. arrangement is much the same, and it is largely by reason of concentrated engineering skill and improved production methods that the original " clash" gearbox works so well as it does. Thousands of patents have been taken out in connection with transmission improvements, but we have yet to see the automatic infinitely variable transmission adopted as standard.

Obviously, such a development must come ultimately, unless the power unit can provide very much greater flexibility without sacrificing the existing standards of performance. It would seem, at the present juncture at any rate, that the latter scheme is not a practical possibility. We must concentrate, therefore, upon change-speed devices which call for less attention on the part of the driver and considerably less work on the part of the maintenance engineer. Transmission overhauls are responsible for far too great a proportion of total costs, and occasion too much loss of time to be considered, even in their present highly developed forms, really satisfactory.

The clutch, as the first step in the transmission sys tern, has been improved as regards ease of operation and long life, but it cannot yet be claimed that perfection has been attained, or that the very basic principle of the, friction clutch is an ideal one.

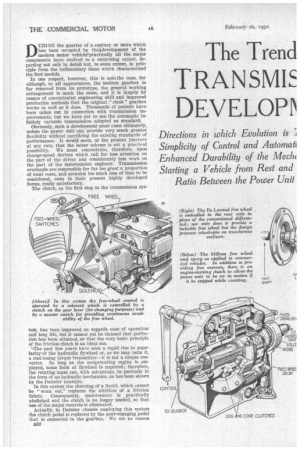

'-.The past few years have seen a rapid rise to popularity-of the hydraulic flywheel or, as we may term it, a cushioning torque transmitter—it is not a torque converter. So long as the reciprocating engine is employed, some form of flywheel is required ; therefore, the rotating mass can, with advantage, be partially in the form of an hydraulic mechanism, as has been shown by the Daimler example.

In this system the churning of a liquid, which cannot be "worn out," replaces the attrition of a friction fabric. Consequently, maintenance is practically abolished and the clutch is no longer needed, so that one of the major controls is eliminated.

Actually, in Daimler chassis employing this system the clutch pedal is replaced by the gear-engaging pedal that is connected to the gearbox. We see no reason B32 why, in the years to come, this function should not he performed by other means, thus cutting out for ever the trouble of having two feet to do three tasks.

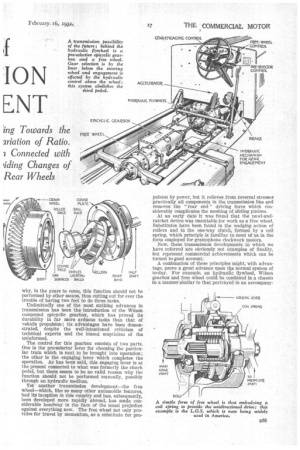

Undoubtedly one of the most striking advances in transmission has been the introduction of the Wilson compound epicyclic gearbox, which has proved its durability in far more arduous tasks than that of vehicle propulsion; its advantages have been demonstrated, despite the well-intentioned criticism of technical experts and the biased scepticism of the uninformed.

The control for this gearbox consists of two parts. One is the pre-selector lever for choosing the particular train which is next to be brought into operation; the other is the engaging lever which completes the operation. As has been said, this engaging lever is at the present connected to what was formerly the clutch pedal, but there seems to be no valid reason why the function should not be performed manually, possibly through an hydraulic medium.

Yet another transmission development—the free wheel—which, like so many other automobile features, had its inception in this country and has, subsequently, been developed more rapidly abroad, has made considerable headway in the face of the usual prejudice against everything new. The free wheel not only provides for travel by momentum, as a substitute for pro pulsion by power, but it relieves from reversal stresses practically all components in the transmission line and removes the "rear end" driving force which considerably complicates the meshing of sliding pinions.

At an early date it was found that the nawl-andratchet device was unsuitable for work as a free wheel. Substitutes have been found in the wedging action of rollers and in the one-way clutch, formed by a coil spring, which principle is familiar to most of us in the form employed for gramophone clockwork motors.

Now, these transmission developments to which we have referred are obviously not examples of finality, but represent commercial achievements which can be turned to good account.

A combination of these principles might, with advantage, prove a great advance upon tile normal system of to-day. For example, an hydraulic flywheel, Wilson gearbox and free wheel could be combined in a chassis in a manner similar to that portrayed in an accompany lag illustration. If a hand-operated hydraulic control be used for the gear engagement, the ideal of "one foot one task" can be achieved, which would provide considerable relief to the driver of a public service vehicle in particular, and to every drive 'r in general. The combination of the free wheel and the hydraulic flywheel would vastly ease the loads on the gearbox, so that maintenance work on this component might easily be reduced to a tithe of what is the normal allowance at the present time in connection with the " clash " type of box.

An alternative to hydraulic control for the gear engagement would be a hand-operated lever; setting in motion a small vacuum servo motor to provide the necessary pull.

There are now several hydraulic systems of transmission under test. One of the most interesting is the Leyland, in which the hydraulic section replaces the indirect ratios, whilst the normal direct drive is provided. At the present time the principal difficulties experienced with this class of design are the heat produced and increased weight, but, in due course, these troubles will be overcome.

Another interesting development of recent origin is the Trojan automatic clutch, which relieves the driver of a good deal of work.

Yet another scheme in connection with clutch operation is that of using the engine inlet-manifold vacuum to operate a servo motor, disengaging the clutch whenever the accelerator pedal is released. This, of course, gives perfect free wheeling, coupled with simplicity and easy gear changing, but for heavy commercial service the problems connected with clutch-facing wear and the heavy loads upon the withdrawal mechanism appear to be barriers to its progress.

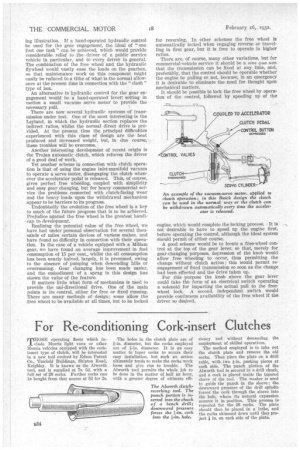

Undoubtedly the evolution of the free wheel is a key to much of the future progress that is to be achieved. Prejudice against the free wheel is the greatest handicap to development.

Realizing the potential value of the free wheel, we have had under personal observation for several thousands of miles certain devices of various makes, and have found no difficulty in connection with their operation. In the case of a vehicle equipped with a Millam gear, we have found an average improvement in fuel consumption of 15 per cent., whilst the oil consumption has been nearly halved, largely, it is presumed, owing to the absence of pumping when descending hills or overrunning. Gear changing has been made easier, and the embodiment of a sprag in this design has shown the value of the feature.

It matters little what form of mechanism is used to provide the uni-directional drive. One of the main points is its control, either for free or fixed running. There are many methods of design; some -allow the free wheel to be available at all times, but to be locked

for reversing. In other schemes the free wheel is automatically locked when engaging reverse or travelling in first gear, but it is free to operate in higher ratios.

There are, of course, many other variations, but for commercial-vehicle service it should be a sine qua non that the transmission can be fixed at any time, and, preferably, that the control should be operable whether the engine be pulling or not, because, in an emergency it is desirable to eliminate the need for thought upon mechanical matters.

It should be possible to lock the free wheel by operation of the control, followed by speeding up of the engine, which would complete the locking process. It is not desirable to have to speed up the engine first, before operating the control, although the ideal system should permit of either course.

A good scheme would be to locate a free-wheel control at the top of the gear lever, so that, merely for gear-changing purposes, depression of the knob would allow free wheeling to occur, thus permitting the change without clutch action ; this would permit reengagement of fixed transmission so soon as the change had been effected and the drive taken up.

For this purpose the knob above the gear lever could take the form of an electrical switch operating a solenoid for imparting the actual pull to the freewheel lock, A second, independent switch would provide continuous availability of the free wheel if the driver so desired.