Distribution trends:

Page 31

Page 32

Page 33

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

The status of management

by John Darker AMBIM

IN the past year or two transport and distribution companies have been enriched by the recruitment of about 350 graduates. Some 140 of these products of universities and polytechnics have been taken on by the National Freight Corporation, or its dependent companies, but it is a feather in the cap of the Road Transport Industry Training Board that over 200 graduates have opted for a career in independent road trans port.

The larger companies in distribution — outside the purveyors of transport services for hire and reward. — have continued a policy of graduate recruitment begun, in some cases. 30 or 40 years ago. That many relatively small family companies have been persuaded to recruit from universities is a sign that road haulage is coming of age.

The 1944 Education Act opened the doors of higher education to all who could profit from it. Head-inthe-sand employers who have not taken advantage of the manpower and wotnanpower on offer in the past decade have possibly dealt their firms a mortal blow.

Bright youngsters of 14 or 15 who before the second world war could have been recruited into the distribution function have increasingly opted for higher education. Self-educated road hauliers and professional transport managers could be forgiven if they took a long time to appreciate how the world had changed, though the parents among them could hardly fail to know that the bright youngster refusing the chance of a heavily subsidized education was a rarity.

I was pleased to learn in a recent discussion with Mr Charles Eastman, the RTITB's veteran management training adviser, that the indus try's intake of graduates and other expensively educated youngsters has shown a very low labour turnover of around five per cent — compared with 16 per cent or more for graduates entering industry and commerce. Mr Eastman has actively sought the help of university appointments boards in recruiting graduates for road haulage.

The well educated youngsters who opt for a career in road transport and distribution do so not because the industry offers exceptionally high starting salaries or, indeed, security, but because of the scope it provides for the exercise of entreprenurial qualities.

Exacting job

Compared with the very large multi-national concerns or the well established household-name firms — banks, insurance companies, major consumer goods enterprises — road transport offers to the well educated youngster the certainty of an exacting job and the chance of substantial bonuses if turnover can be sufficiently boosted.

Although salaries offered in the broad field of distribution have risen appreciably since the 1968 Transport Act, a reading of job vacancy notices suggests that leading employers demand a great deal for their money — one European distribution management post offered a salary of £4,500, which is, in my view, lucicrously low. But hundreds of jobs entailing much arduous responsibility are, presumably, filled at much lower salaries.

The oft-repeated hope that a majority of large manufacturing companies would put a distribution man on the main board of directors does not seem to be happening, noticeably. Distribution functions may be subsumed under the broad "commercial" designation.

The admirable National Survey of Physical Distribution Management published by the consultants, Harold Whitehead and Partners Ltd, showed how varied is the approach of companies to distribution and, alas, how reluctant some companies are to answer questions about their administration. Of 200 companies approached by Whitehead researchers only 52 bothered to complete questionaires; 37 were manufacturers, 9 were wholesalers/ or distributors, and six were professional hauliers/ carriers.

In terms of turnover, 16 of the sample of companies participating

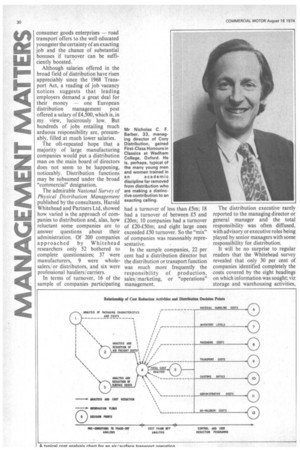

Mr Nicholas C. F. Barber, 33, managing director of Cory Distribution, gained First-Class Honours in Classics at Wadham College, Oxford. He is, perhaps, typical of the many young men and women trained in

an academic discipline far removed from distribution who are making a distinctive contribution to an exacting calling.

had a turnover of less than E5m; 18 had a turnover of between £5 and £20m; 10 companies had a turnover of £20-£50m; and eight large ones exceeded £50 turnover. So the "mix" of companies was reasonably representative.

In the sample companies, 22 per cent had a distribution director but the distribution or transport function was much more frequently the responsibility of production, sales/ marketing, or "operations" management. The distribution executive rarely reported to the managing director or general manager and the total responsibility was often diffused, with advisory or executive roles being played by senior managers with some• responsibility for distribution.

It will be no surprise to regular readers that the Whitehead survey revealed that only 30 per cent of companies identified completely the costs covered by the eight headings on which information was sought; viz storage and warehousing activities, including receipt and despatch of goods, but excluding stockholding; internal transportation; freight transportation inbound and outbound; stockholding of raw material stocks, work-in-progress and finished stocks (including interest on investment, stock losses, insurance, obsolescence, etc); protective packaging; order processing; information/data processing associated with distribution operation; and administration.

Distribution costs

Whitehead concluded that most companies understated their distribution costs and most respondents were only able to quote the costs which had been made available to their department. On average, distribution costs appeared to represent some nine or 10 per cent of sales revenue but to give full credit to the role of distribution the "value added" by the function ought to be included. Goods at the end of a production line or stacked up in a warehouse are a liability until delivered to customers and paid for.

Serious studies of distribution such as that undertaken by Whitehead are slowly dredging up vital data that — in an ideal world — would have been common knowledge several decades ago. There is still far to go before it will be possible to compare the distributive efficiency of one company with another. Just as the value and specification of British or foreign cars or kitchen equipment can be compared, it should be possible to assess the comparative efficiency of distribution of British companies operating on the home market and to compare their performance with a comparable European, American or Japanese operation.

Some people would argue that this will never be possible, but since the elements can be quantified is it not defeatist to run away from the challenge posed? Compared with the task undertaken by all governments of weighing up the military hardware and logistic capability of "enemy" countries, it should be relatively simple to compare distribution system costs across frontiers.

Labour relations

The behavioural sciences have made an increasing impact on listribution in recent years as a result af the impact of labour relations. Both sides of industry are interested n power and it is interesting to ;peculate on the shape of distribuion if one side or the other was able • put its ideas into effect.

A study of the power considera tions in distribution management by I. F. Wilkinson published in the International Journal of Physical Distribution last year, drew attention to the fact that conflicts arise in distribution channels because members of separate undertakings sometimes have incompatible goals, "differing ideas as to the functions each should perform and differing perceptions of reality".

A distribution channel is organized efficiently by the use of power or influence by individual channel members to affect the decisionmaking or behaviour of others in the functional chain. A leadership role may be assumed by one firm eg a container ship operator could seek to control in detail the operations of the several firms in ports, warehousing or road transport involved in an international shipment.

It is not necessary to be an actual transport operator to influence the conduct of a distribution channel. Consider the way in which a valuable customer firm, such as Marks and Spencer, can lay down a precise distribution specification with which transport operators must comply.

I suspect that before long there will be a greater consciousness by transport managements of the power situation in which their dailplives are conducted. A number of firms in a distribution chain may "gang up" together if they each feel oppressed by a larger influence in the distribution channel. An analysis of the power-equation in a distribution channel would provide a stimulating introduction for some graduates entering distribution for the first time.

New brains

The scope for new brains in distribution is vast and the status of the function should continue to grow in future decades. It is a calling that can provide the greatest possible intellectual challenge — comparable to anything offered by an academic discipline. That is not to say that holders of second or third-class degrees cannot make a welcome contribution to a service industry still short of brainpower, influence and status.