By John F. Moon,

Page 47

Page 46

Page 48

Page 49

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

A.M.I.R.T.E.

/T would be difficult to imagine a more restful and comfortable method of road travel than that offered by long-distance coach operators in the United States. While in that country I travelled by Greyhound Scenicruiser from Detroit to Chicago and back.

The scheduled time for the 280mile single journey is 7 hours .10 minutes, including two stops totalling 45 minutes. This is equivalent to an overall average speed of 39.5 m.p.h., or, excluding stops, an average running speed of 43.5 m.p.h.

Such schedules are, of course, made possible only by an excellent road system but, good as it is, most operators are already looking forward to the new 42,000-mile network of expressways, construction of which is already under way. They foresee that its completion will enable even faster running schedules to be put into operation.

Thirteen Divisions Before leaving Detroit I was able to meet Mr. L. J. Stewart, vicepresident of the Great Lakes Greyhound Lines, one of the 11 passenger divisions of the Greyhound Corporation,who also run goods transport and car-hire divisions.

Mr. Stewart, who has been in the passenger transport industry for many years, was able to outline to me some of the problems confronting long-distance coach operators in America, from which it appeared that one of the biggest difficulties concerned operation of routes which pass through more than one State.

Any public service vehicle running in any State in which fare-paying passengers may be picked up or dropped must be licensed_ in that State. This means that in many cases coaches have to carry six or more licence plates, the tax payable being based on the weight of the vehicle. This varies from State to State, but invariably is expensive.

" Pool " Services

Several years ago it was common to find coaches running only to the boundaries of their base States, but nowadays through " pool" services are operated. Several companies pool their coaches on long through-State runs, so that vehicles from several States will each cover the whole trip in turn and thereby dispense with the need for passengers and baggage to be transferred from one coach to another en route. The longest of such services is from Chicago to Los Angeles, a distance of about 2,000 miles, which is covered in 64 hours, including rest stops.

1312 Coaches engaged on this sort of work must, naturally, be designed to suit the legal requirements of all the States through which they may pass, particularly in respect of length, width and weight. Approval of the running schedules, which must also take into account local speed limits. has to be given by the State public transport commissions or boards.

These boards also have to approve routes and fare changes, and when a new route is under consideration hearings are held. Great Lakes Greyhound Lines have 382 coaches. They form one of two divisions which also run suburban services, in this case between Birmingham and Detroit, for which a fleet of 160 buses is used. The average monthly mileage of the complete Great Lakes fleet is about 5.78m., which is not "large compared with some sections, such as the Western division, Which averages over 8m. miles a month. The total mileage for all the fleets during March, 1957, was 391m., achieved by about 6,000 coaches and 15,000 drivers.

Pride of the fleet are the 1.000 Scenicruisers, which were built by General Motors to a Greyhound design. These magnificent sixwheelers, which are used almost exclusivyty on long-distance services, are 40 ft. long and have two General Motors four-cylindered two-stroke oil engines mounted longitudinally at the rear in the form of a 1400 V and together develop 300 , b.h.p. and 740 lb.-ft. torque.

Scenicruisers have 43 reclining i seats, 3 of which are at a raised level to alio the use of large underfloor luggage lockers and to make the best use of the available interior length, Air suspension is employed, as on all subsequent Greyhound vehicles, and a fully-laden Scenicruiser turns the scales at about 18 tons, compared with the 121-ton gross vehicle weight of the conventional twin-axied 39-seaters.

Although the Scenicruisers are decidedly more expensive to operate than any of the other coaches used, particularly in respect of tyre wear, they have proved to be a resounding success and have contributed more than anything else towards the continued popularity of coachtravel in America. The national average monthly mileage for each Scenicruiser is 14,000 and the average fuel return from these vehicles is in the region of 6 m.p.g.

So far as the Great Lakes fleet is concerned, their suburban buses, which, of course, have torque-converter transmissions, average 5.1 whilst the inter-city coaches yield 6.4 m.p.g. These figures are much lower than the national average, because of the peculiar operating conditions in the Great Lakes area.

These conditions are also reflected in the fares, the sparsely populated sections of the State necessitating a slightly higher rate than the national average. The Great Lakes fare structure is based on a rate of 2.52 cents (2.15d.) per mile, whereas the national average is 2.20 cents (1_87d.) per mile. These figures are 0.14 cents and 0.1 cents higher, respectively, than last December.

Greyhound coach services are run round the clock and even the suburban services operate 22 hours every day, with a break between 2 a.m. and 4 a.m.

Regular maintenance programmes are carried out, however, and on long-distance runs coaches are serviced at intermediate points.

Coaches and buses are one-man operated. In the case of the buses, passengers pay a flat fare into a box adjacent to the driver, in return for which they are issued with a ticket. Passengers requiring change can obtain this also from the driver.

In the case of the coaches, the driver is responsible for loading baggage and collecting and checking passengers' tickets. Except on a few extreme-distance services, no seat reservations are made.

Mr. Stewart told me that with the exception of greater engine reliability, he could think of no drastic changes in coach design from which could be derived a particular benefit in the immediate future. He believed that the power of coaches was generally adequate, certainly for the 60 m.p.h.

to which all Greyhound vehicles are governed, and he recalled few instances of brake failure.

He had nothing but praise for the General Motors-Firestone air-suspen sion system and recalled that the few changes in spring bellows were the result of external damage, as opposed to structural failure.

This suspension had been successful regardless of conditions of opera tion, and ambient temperatures in which coaches were operated varied from as high as 125° F. to —50° F. Passengers everywhere commented upon the smoothness of the ride.

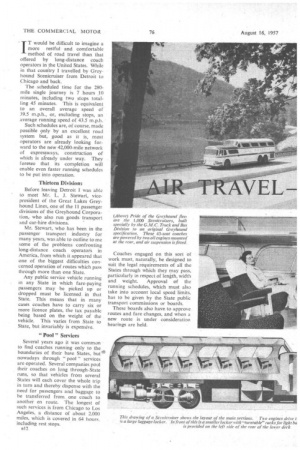

Departure Procedure • The coach on which I travelled from Detroit to Chicago was Scenicruiser No. G-7261, and it was timed to leave the Detroit Greyhound bus station at 2.30 p.m. On arrival at the station passengers buy their tickets in the lobby and are told at which gate their vehicle will be waiting, whereupon they queue at the gate.

About 10 minutes before departure time, boarding starts and the tickets are collected by the driver who waits by the coach door, while baggage attendants label and stow away all heavy articles in the underfloor. lockers. 85° F., and it was equally hot and muggy inside the coach. However, as soon as the driver, Ray Thomas, started the engines, the air-conditioning system was put into operation and, with all the windows shut, the temperature and humidity were reduced to a comfortably low level within 15 seconds.

Reversing out of the loading bay was a slow business, because of the size of the vehicle, but, after a further hold-up by a passenger who had forgotten something, the coach left the station only five minutes late.

Little time was spent in the heavy traffic of Detroit and within five minutes of leaving the station we were on the Edsel Ford expressway, which leads westwards out of Detroit and, at a speed exceeding 50 m.p.h., were overtaking most cars and trucks on the road.

About 20 miles west of Detroit, on the U.S.12 route, there was a five

minute delay occasioned by road repairs. This time was spent for the

most part in bottom gear, with the result that we arrived at Jackson for the first scheduled rest stop at 4.25 p.m. This was 10 minutes late, although the coach had been keeping up a steady 60 m.p.h. once clear of the road works. Jackson is 72 miles from Detroit.

The journey was continued at 4.45 p.m., by which time we were 15 minutes behind schedule, and further time was lost in leaving Jackson because of traffic. It was difficult to maintain a particularly high speed along the M.60 road between Jackson and Niles because it has only two lanes.

However, the rapid acceleration possible with the coach, by use of the two-speed clutch system of the sixspeed transmission, made overtaking with the 40-ft.-long vehicle a comparatively simple matter and the distance between Jackson and Niles was covered in the scheduled time.

25 Minutes Late

Unfortunately, certain passengers were slow to board after the Niles dinner stop. Accordingly, we were 25 minutes late by the time we got out on the open road again. Within 10 minutes of leaving ' Niles, the Michigan-Indiana State line was crossed, 95 miles from Chicago, and five minutes after that we joined the Indiana toll road, which is a two-lane limited-access dual carriageway and typical of the new type of American highway.

From this point on it was 'flat out" to Chicago, there being nothing to stop progress. So boring can driving on these turnpikes grow,

in fact, that the _highway authorities have hadto-put in artificial curves now and again to relieve the monotony and prevent drivers becoming. mesmerized by driving mile after mile at high speed along

straight, level roads.'

The Indiana toll road was left shortly after passing Gary, the great steelworks town„ whereupon the coach took to an expressway which led almost into the centre of Chicago. The last three miles, however, became something of an obstacle race. because the route into the Chicago coach terminal twisted its way around, and even under, the central part of the city.

Sharp Turns

Despite the very sharp turns frequently occasioned by this circuitous track, the driver did not seem to experience any difficulty in handling the vehicle, and we pulled into the main station, one of the largest and most modern in the world, at 10.10 p.m.—only half an hour late.

The coach fare for the journey is 58 (£2 17s.), including 10 per cent. Federal tax, whilst the rail fare is 311 (£3 18s. 6d.) and the air fare is 517.88 (k6 7s.). The air fare does not include transport charges to and from the airport. The cost saving is substantial, and neither rail nor air could be more comfortable than the coach. The 280 miles had been covered at an overall average speed of 37,m.p.h. in an actual running time of 6 hours 35 minutes, which is equivalent to 42.7 m.p.h. Yet none of the 30 or more passengers carried throughout the. trip showed any sign of fatigue.

Travelling as a British passenger on one of these vehicles, it is not hard to appreciate what an improvement they are on current European designs. Admittedly,the distances and speed involved and theroutes used contribute in a, great measure towards the evolution of such designs, but I was easily convinced what a great advance the incorporation of air springs alone would be on British coaches. •

Similarly, a i r conditioning, although expensive, is an invaluable attraction to prospective coach 'passengers, and, combined with the air suspension and quietness of the rearmounted power units, provides healthy, untiring travel over long distances and contributes towards the prevention of travel sickness.

Air suspension almost eliminates the small vibrations normally experienced on the open road. The larger bumps which cannot be completely absorbed do not cause continuous pitching and register only as a single bump per wheel with no after-effects. The General. Motors system of levelling valves, furthermore, ensures automatic compensation against. roll when cornering and, of course, is .self-levelling, irrespective of the load or its position relative to the axles.

During one of the rest stops, Ray Thomas told me that most' Greyhound drivers enjoy handling the Scenicruisers ,because, despite their size, they were extremely, easy to manage.

Complicated Transmission .

His only slight criticism was that some of the coaches occasionally gave transmission trouble, the transmission being a complicated device with a hydraulic coupling linking the two engines, and a two-speed, fourplate wet clutch interposed between the fluid coupling and the three-speed synchromesh gearbox. This clutch gives direct or overdrive ratio and is operated by an electro-hydraulic selector valve controlled by a shift switch on the gear-lever knob.

The significance of thii " Achilles heel" in the transmission was shown during the return trip to Detroit, which was made overnight. On this journey a half-hour stop was occasioned at South Bend because the clutch needed topping up with fluid, which accounted for the coach being half an hour late into Detroit. Otherwise, the journey would have been completed according to schedule and without loss of sleep.