1. Established transmissions with an assured future

Page 32

Page 33

Page 34

Page 38

Page 39

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

BECAUSE it would be uneconomic to design a gearbox for every heavy-vehicle engine produced, a gearbox in this category is, typically, one of a family of units based on the same main section. The maximum number of ratios that can be accommodated in a single housing is normally six, and the centre distance between the bearings must be reduced to a minimum in order to obviate undue flexing. Depending on the rated rpm and torque back-up characteristics of the engine, a matching fiveor six-speed gearbox will have fairly wide ratios, the higher the rated speed the larger the steps between the gears. If more than six speeds are required additional ratios can be provided by one or more auxiliary units mounted in an extension of the main gearbox or attached to it.

At the outset it is necessary to differentiate between a splitter box, a range-change type and a splitter/rangechange unit and to show how an overdrive gear can, in some form, be used as a splitter or be incorporated in a two-speed back axle for this purpose.

Splitter gear

A splitter gear is used to provide intermediate ratios in the case Of a relatively wide ratio box that would be suitable for application to the same type of vehicle given that the ratio steps were acceptable. Adding a splitter can be done, and normally is done, in a simple way by installing a step-down pair of gears ahead of the main section, which provides a drive from the input shaft to the layshaft having a lower ratio than the layshaft drive in the main section. In some gearboxes a gear of this type is used as an extra low or crawler gear and is controlled by a lock-out mechanism to prevent it being employed as a splitter.

The splitter control is operated as many times as the main control if changes are made in sequence, which is cited as a disadvantage by some operators. Each of the two step-down gears to the layshaft are used alternatively with different ratios engaged and splitting the gears of a box with uneven ratios can result in one or more of the steps in the splitter version being so small that changing from one to the other is virtually a non-change. Many gearboxes are now designed with splitting in mind to give even steps, notably range-change/splitter units.

In a range-change gearbox the main section is typically a four-speed close-ratio unit that would not be suitable "on its own" as a vehicle gearbox. The range-change auxiliary is mounted at the rear and is driven by the output shaft (not the layshaft) of the main section. It generally comprises a main-shaft /secondary-shaft unit with two pairs of gears, but may be an epicyclic gear.

In high range and in low range, ratio changes are made in the normal way, an additional switch-operated power-assisted control being provided to change from one range to the other. Of particular importance in heavy-duty applications, the torque throughput of the main section in low range is the same as it is in high range whereas, in a splitter box, the torque is increased when bottom gear is engaged. A range-change box thus provides for increasing the torque output from the range-change auxiliary to any usable rating without overloading the gears or bearings of the main section.

An overdrive gear is also mounted at the rear of the main box in most applications, although it may be incorporated in the main section if sufficient space is available. In its more usual form it comprises a step-up gear that is 'driven from the layshaft, and the layshaft thus transmits torque to the overdrive when it is engaged, which may be for longer periods than any of the lower gears apart, possibly, from direct top.

Employing an overdrive in this form has been criticized on the score that it defeats the, accepted design concept that gears should be arranged in descending ratio towards the rear so that bearing loads are largely cancelled out. Because it is driven by the layshaft it cannot be employed to split the ratios but it could be used to provide additional step-up ratios. If fitted inside the main section it should preferably be fitted close to the input to help cancel out the loads but it is more convenient to fit it at the rear.

An overdrive designed to accept torque direct from the output shaft is generally an addition to a spur gear type of range-change system and as such it can be employed as a splitter by stepping up the drive from the

output shaft in each gear. It is important to note that torque is not transmitted to the overdrive from the layshaft. In overdrive top as well as direct top no torque is relayed through the layshaft which is not, therefore, operating under load for a major part of the running life of the vehicle.

Range-change and splitter /overdrive systems are incorporated in a single epicyclic cluster in some applications, engagement being by dog clutch. An Eaton two-speed axle incorporates a high-top or overdrive ratio and is used as a splitter /overdrive unit, the planetary gears of the two-speed mechanism being located behind the crown wheel and pinion. Whereas an overdrive mounted behind the gearbox increases the speed of the propeller shaft (which is undesirable in some applications) shaft speed is not increased if a two-speed axle is fitted. Employing an overdrive as a splitter has the possible disadvantage that what is best for overdrive is not best for splitting.

Normally, a torque converter is part of a torque converter /epicyclic gearbox of the semi-automatic or automatic type but has recently been fitted at the front of conventional types of gearbox to eliminate shock stresses in the transmission line by acting as a damper and to improve easy starting and low-speed operation. Its use in this form represents yet another way of ringing the changes with a main unit.

It is significant that there are at least two eight-speed range-change gearboxes in the pipeline, news of which will be released in due course. In the opinion of some transmission authorities, the splitter box is "on the way out" with the possible exception of some splitter/range-change multiple-ratio units. It is claimed that drivers generally prefer a range-change unit because changes are made in the normal way in both ranges, but splitter changes are typically made by means of a button control with the aid of power assistance, and experienced drivers have reported that splitting is no worry so long as the ratios are spaced to give appropriate steps.

While it is probable that the range-change multi-ratio gearbox has a more important future than the splitter (particularly if the prospect materializes of a cheap form of automatic system being applied to it), a fiveor six-speed box is adequate for many heavy-duty applications if the engine has a good torque back-up. And the simple way in which a forward-mounted splitter gear and /or a rear-mounted overdrive (layshaft driven) gear can be applied to it will probably perpetuate its use for many years yet. As will be explained in the second article in the series, future engine developments may well play an important part in transmission developments.

When a vehicle is being driven on a motorway or equivalent a better performance could be obtained on less severe gradients and when travelling in varying head-wind conditions, if the two or three upper ratios of the gearbox had steps of, say, 15/20 per cent in place of the more usual 50 per cent or more. And a multi-speed gearbox with closely spaced upper ratios and more widely spaced lower ratios would have obvious advantages.

In a range-change or splitter box (as distinct from a range-change/splitter unit) it would be impossible to obtain such ratio variations without undue .complication; but they could be provided in an eight-speed "straight" gearbox. An experimental gearbox of this type was developed by a company in the British Leyland group that comprised a six-speed box with an extension at the front with two additional sets of gears. Unfortunately, application would be strictly limited because it would not have the commercial advantage of being available in a large number of versions covering manifold requirements.

Synchromesh?

Is synchromesh necessary? This is a controversial question. The gearbox of a heavy vehicle should have a useful life of at least 300,000 miles and it is said that the "average driver of today" can do less damage to a constant-mesh box. The wider the ratios the greater the need for synchromesh and, as shown by ZF, power shift can be applied to a synchromesh gearbox to give what amounts to semi-automatic control.

Experienced drivers have however claimed, when driving a vehicle with a multi-speed range-change /splitter box, that they would have been better off with a constant-mesh unit. Operators have said that some UK gearbox manufacturers prefer constant-mesh to synchromesh because they don't know how to build an efficient and long-wearing synchromesh mechanism of a type produced by German and Swedish makers. And UK makers have pointed out that incorporating the heavy-duty' type of synchromesh that is required for long life would add unacceptably to the length, weight and cost of the gearbox.

It is possible to fit a dog engagement gear that affords a "degree of synchromesh" and the makers say that this is the answer. One thing is indisputable. So much depends on the driver. And it is acknowledged that synchromesh should be a feature of a power-shift range-change mechanism and of the transmissions with a lesser number of ratios fitted to lighter vehicles with a relatively short life.

The story is told by a gearbox designer of an operator with considerable technical knowledge who thought that the only way of providing a high overall gear ratio (and high road speed) was to fit an overdrive. And this is probably a common misconception. It is pertinent to re-emphasize that adding an overdrive to the gearbox or using a two-speed overdrive rear axle is a useful means of making the best use of available basic transmission units. Instead of fitting an overdrive in the gearbox or back axle, a direct-drive gearbox could be used in conjunction with a higher-geared final drive. And this would have the advantage that the crownwheel-and-pinion would have a relatively large, more robust pinion.

Axles with a double-reduction gear in the differential assembly, or with hub-reduction gears, are commonly employed to increase the wheel torque available in heavy-duty applications in which the vehicle operates at a relatively low road speed. Hub-reduction gears reduce the torque stresses in the back axle in proportion to the reduction ratio and enable a high-geared crown wheel-and-pinion unit (with a large pinion) to be used. If a suitable axle with hub-reduction gearing is available it can with advantage be fitted on a normal-duty vehicle in place of an axle having a low-geared crown-wheel-and-pinion and no hub gearing. This enables the overall dimensions of the axle (and weight) to be reduced.

Typically, a hub-reduction gear has a ratio of 4 to 1. The Foden hub gear has a ratio of 2 to 1 and is used for heavy-duty applications. It is available as a lock-up unit and in this form is particularly suitable for application to a heavy-duty vehicle, such as a machinery carrier, that is required to operate at double its laden speed when running empty.

A particular method of ringing the changes with a standard gearbox has been successfully tried out in an application to a railcar, but as far as is known, it has not been applied to a road vehicle. If a step-up gear were employed in front of the gearbox and a step-down gear at the back it would be possible to fit a box with a lower torque rating than the rated torque of the engine and this would enable a single unit to be used for a large variety of applications. It was .done many years ago by SCG in the case of a railcar for overseas powered by an engine with a torque rating considerably in excess of the rating of any available SCG (automatic) gearbox. And the railcar is still running!

It may be argued that incorporating both step-up and step-down gearing in a gearbox would involve high weight and cost penalties. But this could be countered by pointing out that a box with a splitter at the front and overdrive at the rear is fitted with step-down and step-up auxiliaries. A high operational speed could produce unacceptable churning losses (dry-sump lubrication would reduce the losses) and this could be a major disadvantage.

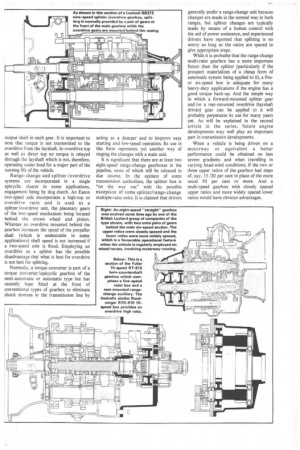

The published illustration of the Leyland GB 272 10-speed splitter /overdrive 300 lb ft torque constant-mesh gearbox .shows a continued on page 36

typical front-mounted sPlitter and rear-mounted overdrive that in this case give a spread of ratios between 0.756 to 1 overdrive and 8.1 to 1 bottom gear. It is based on a five-speed main section with sliding dog engagement of the ratios. Selection of main and low trains is made by two pneumatically operated sliding dog clutches on the layshaft, the dog clutch for low ratio incorporating a synchromesh mechanism.

Comparing gearboxes in a more sophisticated category, mention may be made of a number of Fuller Roadranger twin counter-shaft gearboxes of American origin that are produced with up to 15 ratios, the Foden 12-speed box that is a four-speed box combined with a planetary gear and the German ZF 5S-110GP that is a nine-speed box based on a six-speed unit with an epicyclic auxiliary and is available with a torque converter.

Because the torque of Roadranger transmissions is divided between two layshafts (countershafts), the mairishaft "floats" and the reduced gear stresses enable a more compact assembly to be produced. While the main gearboxes are described as constant-mesh units the teeth of the engagement dogs are coned to assist synchronization. Synchromesh is fitted to the range-change mechanism, which is air operated.

All the Roadrangers are compounded units based on a threeor five-speed main section and a range-change or splitter /range-change auxiliary. The twospeed range-change comprises a twinshaft unit with two pairs of gears; one model the RT-915 (900 lb ft) 15-speed box has a three-speed main section and a range-change auxiliary comprising three pairs of gears. In this case the third pair provides an additional step-down ratio (for the third range) while the similarly located third set of the RTO-913 /1213(900/1200 lb ft torque) 13-speed box, with a five-speed main section, is a step-up overdrive gear that is used as a splitter, one ratio in the main section being used solely as a low or starting gear. In one version, three overdrive ratios are obtainable.

The Roadranger 13-speed box is an interesting example of the way in which splitting the main section can provide a series of close ratios (of 15 /18 per cent) while the steps of the low range are of the order of 34/37 per cent, with the exception of the step between the two lowest gears which is 50 per cent. In contrast the steps of the three-range 15-speed box are between 23.5 per cent and 27.5 per cent. Two of the most popular Roadranger gearboxes in this country, the RT-610 and RT-910 10-speed models, have torque ratings of 600 lb ft and 900 lb ft respectively and are based on a five-speed main section.

The Foden 12-speed box has a nominal torque rating of 700 lb ft and is applied to all the company's 21 models, an Allison semi-automatic torque-converter transmission being optional on dumpers. Only one version of the gearbox is produced, which reduces the production cost to a minimum. While it would be possible to ring the changes, would not be possible to offer versions with fewer gears at a lesser cost. In effect some operators are getting more than they pay for.

An overdrive/splitter section is included in the range-change/splitter epicyclic gearbox, changes being pre-selected and air-operated. The planetary gears are dog engaged and occupy little more space than a single pair of spur gears.

The ZF nine-speed box comprises a four-speed mail box in which a crawler gear is incorporated and the two-speed range-change epicyclic unit doubles the number of ratios of the main section. All the ratios, apart from the crawler and reverse gears, are engaged by lock-synchronizers and the pneumatically operated rangechange is also fitted with a synchronizer of this type.

If equipped with a torque converter the power is transmitted through a plate clutch, which is a necessity in the case of a conventional layshaft transmission to enable ratio changes to be made. The system is then known as the WSK and it can be fitted with a device that disengages the clutch when the gear lever is moved. It thus eliminates the need for a clutch pedal.

It has been demonstrated that the ratios of the box in standard form can be power-shifted with the aid of an air-powered clutch system operated through the ratio-change lever which allows it to operate as a semi-automatic. ZF synchromesh mechanisms are generally acknowledged to be long wearing as well as efficient. In a power-shift application they would need to be both long wearing and efficient.

The advantage of applying a torque converter to a standard type of manual gearbox was highlighted in a short practical test by CM of the Volvo R60 heavy-duty eight speed range-change synchromesh gearbox equipped with a converter giving a relatively low-torque multiplication of 1.9 to 1 (CM, November 7, 1969) which almost doubles the tractive effort available. In converter form the box is known as the MR61.

The converter can be locked in and out with a flick switch and it was reported that starting from rest was like driving an automatic and that ease of driving in town traffic was its most notable advantage. The R60 is also available as a 16-speed range-change splitter box.

In a road test of a Volvo FB88 6 x 2 /Parator 38-ton-gross tractor/trailer combination carried out in Sweden (CM, June 19, 1970) it was said of the 16-speed box that the transmission was of great benefit when ascending long hills because exactly the right ratio could be obtained for the gradient and the engine kept at its peak torque for the entire climb. Adding a splitter increases the length of the gearbox by only Sin.

These comments on established types of transmission give some idea of the problems involved in planning a transmission by making use of well-established conventional types of available unit. A well-known gearbox designer has said that it is impossible to plan ahead because future diesel-engine designs are unpredictable. In line with the thinking of the majority of transmission specialists he prefers an engine providing a good torque back-up and would opt for an engine having a constant horsepower characteristic at the upper end of the power curve. But the development (and application) of such engines is currently frustrated by the bhp /ton regulations.

A review of engine/transmission matching problems and of engine characteristics that have to be taken into consideration in the choice of a suitable transmission is the theme of next week's article. METRICATION carries more implications for road transport than are immediately apparent, and last week's publication of the Metrication Board's second report permits stock to be taken of the situation.

That there is a growing need for an improvement in communications generally regarding metrication is realized by the Metrication Board. It says so specifically. The fact that the transport industry is waking up to the same thing is reflected by the establishment by the Road Transport Industry Training Board Of a working party to consider the effects of !metric change on haulage and make recOmmenddions. It needs to act soon, bearing in mind that metrication is already sOrting to have a direct affect on some sectors of the industry notably tipper' work, sand and gravel having gone metric on January 1 this year. The immediate interest of freight transport is in rates and Charges so it is not surprising to find the Board reporting that the main object during the year has been to establish metric freight tariffs.

Target date However, the target date for metrication of inland freight traffic will not, after all, be January 1 1972, as originally planned. Opposition by British Railways and the Post Office appears to be the main reason. British Railways told the Board they foresaw great difficulties in preparing the necessary coherent metric tariffs in the time available and in training staff to operate them, so soon after decimalization of the currency. BR was most unwilling, for commercial reasons, to move in advance of the Post Office, and also doubted whether customers would willingly accept so early a date for the change.

As a result, says the Board, "with some regret, because of the potential inconvenience to those who use both overseas and inland transport services, we have concluded that the target date for January I 1972 is not practicable for inland freight." It goes on: "We shall continue to seek the agreement of all concerned on the most suitable later date. We still trust that it will be possible for the change to be made on January 1 1972, for overseas freight, since we are satisfied that this is the wish of the majority of those interested. A final decision will depend on the outcome of the inquiries now being made by Customs and Excise and on a decision by the Government to introduce the necessary changes in Regulations." The impact on Customs and Excise documents is, apparently, so extensive that • completely new forms are required for practically every purpose.

Difficulties resulting from the different dates of change for the two kinds of service (overseas and inland) will, says the Board, be much diminished by the fact that most of the major carriers, including BR are already willing to accept, by prior arrangement, inland traffic offered in metric terms. It adds that this readiness to meet the convenience of individual customers in advance of the general change will no doubt spread.