The Cost of COLLECTING HOUSEHOLD REFUSE

Page 128

Page 130

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

How the Charges for the Collection of Waste Material may be Calculated Beforehand, Given Some Knowledge of the Conditions.

rilHERE are plenty of opportunities for the examina

tion of the figures for the cost of operation of municipal vehicles, and it might seem that it would be easy to compile a schedule of operating costs of such vehicles, the table being similar in form to he wellknown Tables of Operating Costs which are published by The Commercial Motor.

As a matter of fact, the task of compiling such a table, instead of being easy, is almost impossible to accomplish, because the circumstances vary so much in every case. To arrive at average costs some basis for calculation is necessary. In the case of tables for commercial vehicles the mile or the hour serves as such basis. In municipal service neither of those factors is of use, nor is there any other which will serve.

The Cost of Refuse Collection.

Refuse collection is perhaps the most important item in the work of a municipality. It is the item concerning the cost of which most information is available, and the one that can be most easily considered from the point of view of regularity of cost.

The outstanding difficulty in this matter is, as I have stated, that of finding a common basis for assessment.

I have previously suggested the cost of a day's work as being suitable. This needs elaboration in the shape of instructions in the use of the information embodied in tile tables to avoid mistakes. My view is that, given the cost per day of operating any type and size of vehicle (or combination of vehicles), the Intending user can, with experience of the local conditions, arrive at a figure for total cost of collection, using those tables of costs.

Where Experts Disagree.

There is no point in giving data for cost per mile: the mileage run by municipal vehicles is mainly small, and certainly that covered -by those employed in refuse collection is negligible; or, at any rate, so small that the cost, calculated on the mileage basis, would seem absurdly high.'

The The authorities themselves are not in agreement on this point, either. The Ministry of Health asks for returns per ton of refuse collected. Cleansing superintendents, in general, prefer to take the cost of collection per 1,000 houses as a basis, and at this juncture I might recount an experience because it so aptly illus trates the point I an trying to make. .

It is the habit of the Ministry to reprimand—if I may so use that word—any cleansing superintendent or surveyor whose costs, in the opinion of the Ministry, are higher than they should be. In pursuance of that policy the Minister wrote recently to a certain town council pointing out that the cost per ton of refuse collected in that town was high.

The cleansing superintendent, who was, as a matter of fact, very far from being the inefficient official the Ministry considered him to be, was in due time called upon by the council to give reasons for these alleged high costs, whereupon he quickly demonstrated that instead of his costs being higher than those of the authority which was held up as an example of an efficient motor-vehicle operation, they were lower on a basis of cost per tow houses, which basis, as the superintendent showed, was the only fair one. The refuse in his town was bulkier and lighter than that of the other town, and that fact accounted for the difference.

n42

Refuse May be Heavy—or Light.

Now, there is in that story information which may surprise manyreaders. There is considerable difference between the bulk of refuse to be collected in one town and that of another. In industrial centres, where It is the rule for most of the families to have all meals at home and where coal fires are largely used for heating and cooking, the refuse is heavy, consisting mainly of ashes, damp and heavy vegetable and organic materials. In other places, where the nature of the staple industries is such that women are chiefly employed and where tenement houses are in the majority, it is more generally the case that the principal meals are taken away from home. Moreover, whatever cooking be done is carried out in gas cookers, whilst heating, too, is effected by means of gas fires. In this case the refuse is bulky, but light. The extent to which the weight of refuse varies is strikingly indicated by the accompanying table, showing the weights per cubic yd. of refuse collected in a variety of provincial towns. I am indebted to Mr. Rex Bundy, of Shelvoke and Drewry, Ltd., for (he information on which that table is based.

In view of these figures, it seems obvious that the cost per 1,000 houses is a more rational basis than the cost per ton, since the conditions of the work of collecting a bin from a house are not greatly affected by the weight. It is generally agreed that an important factor in deciding the cost is the quantity of refuse that the loader can collect per hour or per day. The bins are something near equal in size, so that, so far as they are concerned, the difficulty of handling them Is approximately equal in all cases. That being so, the number of bins which can be collected in a day is the principal factor in th:t. cost of refuse collection and not the weight of the contents of these containers. The equivalent of that, the cost per 1,000 houses, is, therefore, the proper basis for the compilation of tables showing the cost of the collection of waste material from households.

Linking-up Cost of Collection and Cost of Transport.

With the capabilities of the human element, the loader, as a basis, it is possible to link up the cost of refuse collection with that of its transport, and thus obtain a total. To begin with, it must be within the knowledge of every cleansing superintendent that his loaders, under the peculiar local conditions, are capable of collecting a given number of dustbins per day and emptying them into a vehicle. He has, therefore, at his disposal, three factors of the cost of operation: the number of bins each loader can handle per day, the number of loaders he can employ on any particular route and the wages he will have to pay those loaders.

The next item of information needed is the time

Involved in transferring the contents of the refuse containers to the vehicle. This varies, of course, with the type of machine, but it is obviously less when the loading level is low enough to enable the bin to be emptied directly, without the loader having to climb a ladder for the purpose. Given an approximate calculation of this time, the superintendent can arrive at a figure for the number of bins which a certain number of loaders can transfer from house to vehicle in a working day, and from that information he can discover the cost of that collection. He needs only the cost of operation of the vehicle he employs to enable him to give a complete estimate of cost of refuse collection per 1,000 houses.

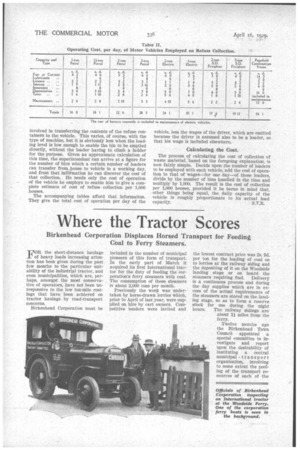

The accompanying tables afford that information. They give the total cost of operation per day of the vehicle, less the wages of the driver, which are omitted because the driver is assumed also to be a loader, so that his wage is included elsewhere.

Calculating the Cost.

The process of calculating the cost of collection of waste material, based on the foregoing explanation, is now fairly simple. Decide upon the number of loaders to be employed with each vehicle, add the cost of operation to that of wages—for one day—of those loaders, divide by the number of bins handled in the time and multiply by 1,000. The result is the cost of collection per 1,000 houses, provided it be borne in mind that, other things being equal, the daily capacity of the vehicle is roughly proportionate to its actual load capacity. S.T.R.