Scannell Trunker 11/Challenger 31-lon-gross orlic

Page 78

Page 79

Page 80

Page 83

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

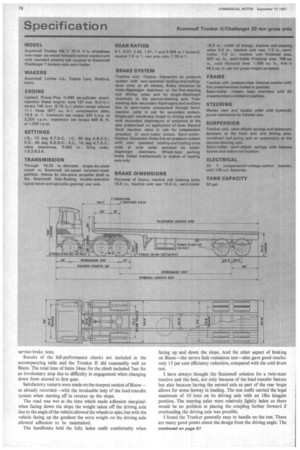

BY A. J. WILDING AMIMechE, MIRTE PICTURES BY DICK ROSS WHEN Scammell introduced the Trunker II it became the first vehicle manufacturer to offer a tractive unit with two steering axles. This design was chosen simply to get to the maximum UK permissible weight of 32 tons with the minimum weight penalty: 32 tons is allowed on a four-axle artic but axle outer-spread must be 38ft. and a five-axle outfit is almost essential.

Other manufacturers have since designed twin-steer tractive units for 32 tons, most with the two steering axles mounted as a front bogie and some with the second steering axle set close to the driving axle like the Trunker. There is now also a German tractive unit for 38 tons with a set-back second axle.

But in one respect the Trunker II remains unique: the second axle has combined air-and-leaf-spring suspension and—by exhausting the air from the air springs—load can be transferred to the driving axle. This is one of the most important features of the Scammell design as with a 10-ton axle load (the maximum in Britain) there can be adhesion difficulties when a gross weight of over 30 tons is involved.

An axle-weight-to-gross-weight ratio of 1 to 3 is generally considered desirable. It is interesting that a recent German introduction of a 6 x2 tractive unit for 38 tons with trailing rearmost wheels has a load-transfer system to add weight to the driving wheels in circumstances of low adhesion.

Load-transfer devices for single-drive six wheelers are not new. But the Scammell design scores over the German method because with the load transfer in operation the coupling centreline is in front of the driving axle. "Bucking" of the tractive unit when starting off is highly likely with the German design.

No such problem exists with the Trunker II. Some load is also transferred to the front axle and during this road test the value of being able to transfer weight to the driving axle was confirmed on the hill-climb checks. Wheel spin prevented a reverse restart up a 1 in 6.5 gradient but with the extra two tons on the driving axle there were no problems.

The best results on the test were for braking: very good stopping distances were returned. In general, however, performance was not very exciting and not up to the standard that has come to be expected of current maximum-gross designs.

And fuel consumption was on the low side—about 5.5 m.p.g. compared with at least 7 m.p.g. for 30-ton artics previously tested and 6.5 /7 m.p.g. for a British 32-ton outfit tested earlier this year.

Basically the Trunker II is a 10ff-wheelbase Handyman III with an additional steering axle. The unladen weight is about 1 ton more than the Handyman so that the Trunker can carry about an extra ton of payload The Trunker II engine is the Leyland 0.680 diesel which produces 200 b.h.p. at 2,200 r.p.m. and 548 lb.ft. at 1,200 r.p.m. Transmission is through a Scammell six-speed gearbox to the firm's spiral-bevel-and-epicyclic double-reduction rear axle.

Its braking system is designed to meet the latest Construction and Use Regulations and triple-diaphragm chambers are employed at the first front axle and the driving axle. The third diaphragms of the front-axle chambers and the auxiliary line to the semi-trailer are pressurized for the secondary system by a hand-reaction valve in the cab. The secondary diaphragms of the driving-axle units are pressurized on application of the handbrake to give air assistance.

Location of the second steering axle is by a single-leaf spring and the main suspension is through double-convolution air bellows between the leaf-spring pads and the undersides of the chassis side members. In normal use, air pressure in the bellows is maintained at 70 p.s.i. A switch in the cab enables air to be exhausted for greater traction.

In the unladen condition, the second-axle wheels come clear of the ground and on the outfit tested operation of the load transfer in the laden condition reduced the load on the second axle by 3t 8cwt—to lOcwt 3qr. Of this, 2t 1.5cwt was applied to the driving axle and the remainder to the front axle.

All the tests except for the empty fuel consumption runs were carried out at just over the 32-ton limit. Fuel consumption was checked first and the results can be seen in the accompanying table. The route used—south of Luton on the A6—is not particularly arduous being slightly undulating with one fairly severe gradient necessitating changes down.

There is a gradual upward gradient for the first mile or so of the northern half of the out-and-return run and on a first check, top gear (the 0.666 overdrive ratio) was engaged too early which resulted in a fairly low average speed. But consumption returned was exactly the same-5.4 m.p.g.—as on the second check which increased the average speed to 32.1 m.p.h.

The laden run on M1 was hampered to some degree by four miles of roadworks but this did not affect the Trunker significantly as it would have done a higher-performance vehicle. Although the maximum speed of 55 m.p.h. was attained where possible the average speed for this run was 36.4 m.p.h. which gives an indication of the effect of the gradients on this admittedly severe stretch of motorway the speed was brought down to 20 m.p.h. at one time.

Acceleration tests confirmed the low standard of performance of the Trunker II. Only one artic tested in recent years has taken more than 50sec to accelerate from 040 m.p.h. Very little performance was obtainable in overdrive and it would have required a perfectly flat road of some considerable length to get times for acceleration up to 40 m.p.h.: maximum in direct drive was 36 m.p.h., so overdrive would have been needed. Maximum speed in the four lower gears was 4, 8, 13 and 22 m.p.h.

On the checks on the service brakes there was no locking at all from the tractive unit wheels although the brakes on the leading axle of the trailer locked for a short distance each time.

The three other brake-operating systems were checked separately, with the hand reaction valves for the outer-axle secondary system and the trailer bogie brakes and the air-assisted handbrake. All were satisfactory and when the handbrake was applied at the same time as the secondary system a Tapley-meter reading of 50 per cent was obtained compared with 65 per cent on the

service-brake tests.

Results Of the hill-performance checks are included in the accompanying table and the Trunker II did reasonably well on Bison. The total time of 6min 34sec for the climb included 7sec for an involuntary stop due to difficulty in engagement when changing down from second to first gear.

Satisfactory restarts were made on the steepest section of Bisonas already recorded-with the invaluable help of the load-transfer system when starting off in reverse up the slope.

The road was wet at the time which made adhesion marginal: when facing down the slope the weight taken off the driving axle due to the angle of the vehicle allowed the wheels to spin; but with the vehicle facing up the gradient the extra weight on the driving axle allowed adhesion to be maintained.

The handbrake held the fully laden outfit comfortably when

facing up and down the slope. And the other aspect of braking on Bison-the severe fade resistance test-also gave good results: only 15 per cent efficiency reduction, compared with the cold drum test.

I have always thought the Scammell solution for a twin-steer tractive unit the best, not only because of the load-transfer feature but also because having the second axle as part of the rear bogie allows for some leeway in loading. The test outfit carried the legal maximum of 10 tons on its driving axle with an I8in kingpin position. The steering axles were relatively lightly laden so there would be no problem in placing the coupling farther forward if overloading the driving axle was possible.

I found the Trunker generally easy to handle on the test. There are many good points about the design from the driving angle. The continued on page 81

power steering system is particularly good, giving a light action and a satisfactory "feel". On first taking over the vehicle I had a tendency to over-correct but soon got used to the action. In the unladen condition the steering did not feel over-light and there was no tendency to wander about the road.

Switches, controls and instruments are conveniently placed and the clutch required no excessive effort to operate. The brake treadle application could not be faulted; it was possible to make smooth and progressive stops both laden and unladen.

The Trunker had a Clayton Dewandre load-proportioning valve at the driving axle which prevented over-braking when unladen but the brake balance in this condition was still reasonable as there was no tendency to lock the front wheels on light brake applications. The semi-trailer bogie did not have similar equipment yet the trailer wheels were not prone to locking when no load was being carried.

I was surprised that the Trunker felt so short of power because the chassis I have recently tested with the Leyland 0.680 engine at 30 tons has not been open to criticism in this respect. The extra two tons weight should not have made all that difference and it may have been that the engine needed some minor adjustments.

An indication of this was the fact that a fair amount of smoke was pushed out of the exhaust particularly at high engine speed. This factor, too, could have marred fuel consumption.

But another factor in the performance was the gear ratios. As will be seen from the figures already quoted for the maximum gear speeds there was a big gap between fifth and overdrive top and it was in the speed range above 30 m.p.h. that lack of power was most noticeable.

One of the more difficult things I found to master in driving the Trunker was the gear change. Scammell uses a visible-gate system, the lever being located in a casting which defines the path required to select the various ratios. An advantage is that the wrong gear cannot be selected but a disadvantage is that the lever can only be ' moved from one gear into the next higher or lower ratio. So, when coming to a stop with overdrive engaged, selection of first for the restart requires consecutive engagement of each ratio in the box.

I managed to master the technique required to change gear cleanly by the end of my two days with the Trunker. If imprecise changes were made I found it hard to disengage one ratio as well as to engage the next. Surprisingly, upward changes were more difficult than those downwards but a factor in this was that engine revs died down quickly; this is basically a good thing as when one is used to the vehicle very quick changes can be made.

There was some bounciness of the front suspension on uneven roads and the noise level in the cab was fairly high. But apart from these points the driver could be fairly comfortable. The Cox seat in the Trunker is a good design and incorporates a useful degree of adjustment including the angles of the seat and back. Visibility is very good and the convex mirrors fitted by Scammell gave an excellent view to the rear although as usual with slab-fronted cabs they very quickly got covered with thrown-up rainwater.

This is the first vehicle with over-wheel entry tested for some years but access was aided by good step-rings on the front wheels and well-placed grab handles.

The Trunker II looks to be a very robust design and the same can be said of the Scammell Challenger semi-trailer used with it for the tests. I would like to have seen two-speed landing gear fitted to reduce the amount of effort required to lower the feet to the ground when uncoupling and I was surprised at the amount of wear on the coupling plate and turntable after a fairly short mileage. Obviously the trailer plate was not flat.

As tested the Scammell Trunker II (introduced in June, 1965) has a list price of £4,625 and the 34ft-long semi-trailer costs £1,721 (total cost: £6,346).