Memory testing

Page 67

Page 68

Page 69

Page 70

Page 71

Page 72

Page 73

Page 74

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

Our past technical editors pull out some fascinating stories from eir store of roac-test memories

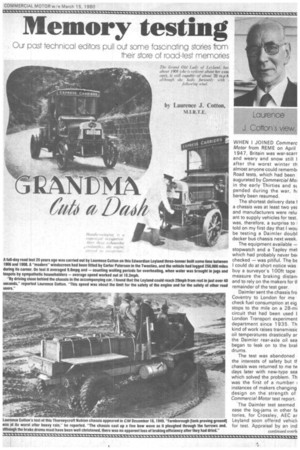

WHEN I JOINED Commerc Motor from REME on April 1947, Britain was war-scarr and weary and snow still I after the worst winter th almost anyone could remembi Road tests, which had been augurated by Commercial Moi in the early Thirties and st. pended during the war, h; barely been resumed.

The shortest delivery date I a chassis was at least two yez and manufacturers were relu ant to supply vehicles for test. was, therefore, a surprise to I told on my first day that I wou be testing a Daimler doubl decker bus chassis next week.

The equipment available — stopwatch and a Tapley met which had probably never be( checked — was pitiful. The be I could do at short notice was buy a surveyor's 100ft tape measure the braking distani and to rely on the makers for tl remainder of the test gear

Daimler sent the chassis fro Coventry to London for me check fuel consumption at eig stops to the mile on a 28-mi circuit that had been used London Transport experiment department since 1935. Th kind of work raises transmissic oil temperatures drastically ar the Daimler rear-axle oil sea began to •leak on to the bral, drums.

The test was abandoned the interests of safety but tF chassis was returned to me tvs days later with new-type sea which solved the problem. Th was the first of a number instances of makers changing design on the strength of Commercial Motor test report.

The Daimler test seemed ease the log-jams in other fa tories, for Crossley, AEC ar Leyland soon offered vehicli for test. Appraisal by an ind

dent source was seen to e great value in sales pro:ion, particularly in export .kets.

iomething had to be done ut test equipment and I had ilibrated fuel tank made. Fuel isumption had previously n ascertained by the unreli? method of measuring the ntity required to top up the <, which invited air locks in corners or ends. My calibtd tank was first used in testa Proctor, the existence of ch was deservedly short.

also bought special brassid thermometers to measoil temperatures. My original rmometer, graduated to little re than 100 C, burst, deking glass and mercury in a r axle.

This calls to mind the test of a udslay twin-steer six-wheeler ich the makers supplied for t with great reluctance after 'longed persuasion. It had an arhead-worm-drive axle, .orious for surface scuffing of wormwh eel.

During the test the ascent of a -ly long hill in Worcestershire sed the axle-oil temperature rmingly. The makers corm: ined bitterly of the inclusion this fact in the report but :itly admitted its validity by anging to a hypoid axle, as ?d by others.

I was less than satisfied with method of measuring brake tance by stamping on the dal when passing a fixed ject and running out the tape to that point to the driver's 3t when the vehicle came to st. The Road Research boratory, then at Slough, was ing Commercial Motor tests comparative purposes and is aware of my difficulties in measuring stopping distances accurately.

So the Laboratory, in conjunction with this journal, developed a gun that fired a coloured slug on to the road. The slug, coloured with ram dye mixed with light grease, had to be stuffed up the bore of the pistol — and a messy job it was, too. It was, however, most effective.

I had to obtain a licence for 100 electric detonators, which necessitated the police inspecting the office as well as my home, where they were usually kept.

One of the most enterprising assignments by Commercial Motor 30 years ago was a series of road (an euphemism if ever there was one) tests in the Middle East. The Anglo-Iranian Oil Co (of happy memory) had spent 00 million on Leyland Super Hippos and another £2 million on spare parts with not entirely satisfactory results. On a three-week visit to the Middle East I was allowed to drive in a convoy of Super Hippos; the others were driven by Indians and Persians. Halfway up a mountain pass the convoy halted while drivers threw buckets of water over the engines. This immediately explained the large number of cracked cylinder heads.

I was greatly Concerned at the extremely high axle-oil tern• peratures when we reached the top of the pass, but Leyland were even more worried when they subsequently found that a type of oil totally unsuitable for tropical heavy-duty operation had been specified. When the correct oil was used the six monthly replacement of worm drives ceased.

Anglo-Iranian's Bedfords were also having problems, notably engine seizures through loss of water. I tracked down the cause to corrosion by the local water of core plugs in cylinder blocks. The trouble was overcome by fitting heavier plugs of a different material.

Not one of Anglo-Iranian's 12 Commers was serviceable when I arrived in Abadan. The company hurriedly put one through workshops and handed it over to me in first-class condition but without a body. Instead, workshops had welded five one-ton steel billets to the chassis for test.

As the chassis descended a long, winding hill with a sheer drop on one side and rock cliff face on the other, the brakes soon overheated and failed completely. The vehicle was slowed and eventually stopped by dragging it along the rock face. On returning to base I was told that all the Comrners were off the road because they had run out of brakes and overturned — information that would have been little comfort to my widow.

Commer's chief engineer reluctantly agreed that higher lift to the brake cams and heavier drums were required for all the company's vehicles for home and overseas. The Society of Motor Manufacturers and Traders took this report very seriously and, not for the first time, manufacturers complained about this journal's honest and fearless appraisals. They could, however, offer no defence of their shortcomings and designs were improved.

Because of its poor quality, the petrol available in the 'forties was heavily leaded to improve octane rating, consequently valves burned out and cylinder heads were commonly lifted at about 15,000 miles for the regrinding or replacement of valves. New ones were scarce and vehicles were frequently allowed to splutter along without maintenance until their engines refused to start.

I therefore sought the cooperation of the Road Research Laboratory in a series of tests on an Austin 5-tonner, lent by the maker's stores department at Longbridge, to demonstrate the effects of neglect on fuel consumption. First the vehicle was run with the engine in prime condition and then with faults such as retarded ignition, pitted contact-breaker points and fouled plugs. Letters from readers showed that exercise was popular and informative. It could easily be performed with a diesel-engined vehicle.

Because makers could seldom spare vehicles for more than a day it was difficult to keep to a standard test route. Instead I used circuits that began and ended at the factory and included as wide a variety of conditions as possible.

An exception to this general rule was made in the case of battery-electric vehicles. At the end of the 1940s these were fast replacing horses for de-. livering bread, milk and so on, and pedestrian-controlled and driven electric three and fourwheeled milk floats abounded. Some manufacturers made outrageous claims about mileage per charge and operators had no way of assessing performance.

I talked to the Electric Vehicle Manufacturers' Association, which agreed on a standae.d course and provided comprehensive test equipment. My tests covered power consurmstd in travelling non-stop to the stat of a round and on simulated deliveries of up to 30 to the mile. The biter was bit when a manufacturer supplied a pedestrian-controlled truck with a jumbo-sized battery. On the continuous-running test I was still plodding doggedly into the dusk after 22 miles.

Towards the end of my term as technical editor, Continental coach travel and long-distance haulage were growing rapidly and Commercial Motor introduced extended tests. The first was of a Commer coach from Luton to Glasgow and back, during which braking, acceleration and so on were tested, all in 22 hours. A similar run was later made with a Bedford lorry.

One of my last long tests was of a Leyland Tiger in the Welsh mountains, on which I was accompanied by John F. Moon, my successor.

Up to the time when I left Commercial Motor in 1954, the Motor Industry Research Association would not allow the Press to use its tracks and all running had to be done on public roads. We were, however, sometimes able to use Government sites in Surrey to test cross-country vehicles. The Thornycroft Nubian and the Austin Gipsy 4x4 were among those that became almost waterborne. The Gipsy had to be towed out by a tank.

John I-. Moon

;OLLOWING on in 1954 from _aurence (-Bill-) Cotton was a

:rightening but exciting )rospect. We had set a standard or Press road tests that was to ast for many years, and I had aeen an admirer of his work for luite a few years. I used by buy CM when I was serving my time at Morris Commercial Cars Ltd, and even arranged for the magazine to be mailed out to Malaya when I was doing my National Service in 1952/53, mainly so that I could read Bill's test reports!

It was only natural that I should follow Bill's lead in so far as road-test routines were concerned: mainly one-day tests, carried out in the immediate vicinity of the vehicle manufacturer's factory, using an undulating route of about 9.6km (6 miles) for fuel-consumption tests, a flattish piece of road for acceleration and braking tests, and a long hill with a good steep section for engine-power and cooling checks — and also that frightening in-neutral brakefade test .

This short localised route had various advantages: the whole test could be carried out inside one day; sometimes a vehicle could only be spared for a day; and it made it feasible to travel around Europe doing tests of vehicles that were important in terms of design trends but which were not on sale in Britain.

And the technique wasn't all that inaccurate. I remember Ford asking me to carry out a series of tests with a Thames Trader prototype several months before its launch so that they could see how their new truck woul(, compare with the competitior. I tested the Trader over several of the other short routes, and also took longdistance figures, and there wasn't a lot of difference between results.

We did some long runs, mainly with coaches. Bill Cotton and I drove the first Commer coach with TS3 two-stroke diesel up to Scotland and back and we also took a Leyland Royal Tiger chassis round North Wales' mountains. Later, I tested an AEC Reliance chassis between London and Lands End — being an open chassis, the rain never stopped from start to finish. I also took a Rowe Hillmaster coach for a day out in Brighton — well, it was a sunny day, and we did have a pretty girl with us!

But for the most part it was all local stuff, and in any case with a small staff it was difficult to justify more than one day per day, plus half a day to write it up. As it was, it could mean such stints as driving from London to, say, Leyland after office hours (no motorways in those days), doing the test the following day, and then driving back to London the same evening.

I mentioned the Rowe Hillmaster and that is just one make that I tested that no longer exists. Others that remain only in memory include Borward, Harrington, Jensen, Rotinoff, Rutland, Sentinel and Trojan r-iot forgetting those fine buses and coaches built by 'Midland Red' for their own use), while many other famous names have been submerged into the groups that were formed during the sixties and seventies.

The flexibility given by localised testing made overseas tests possible, so giving British readers a chance of knowing what the Continentals and Scandinavians were doing the often making their mouths water at the thought of how powerful and comfortable these vehicles were compared with what was currently available in Britain. I suppose it's fair to say that I put the name of ScaniaVabis (as it then was) on the map, our first test report on a vehicle of this make having been published in December 1954, when hardly anyone outside Sweden had heard of ScaniaVabis.

On that same visit to Sweden that year I also drove Volvo's first production turbocharged truck — the Turbo Titan — but had to wait two years before I could do a full test for publication because in those days even Volvo wasn't 100 per cent confident in its turbocharging abilities. In 1957 we told our readers what a DAF truck w and how it performed (ever tri

doing a hill-climb test in H land?), whilst MAN ar Mercedes-Benz vehicles we given the full treatment in Gi many during the early 1960s.

In 1957 I visited the USA break new ground in that cou try by carrying out commerci; vehicle road tests personal ("D'ya mean you're actual going to drive it yourself? With load?"). So I was able to enji the hitherto unknown pleasu of driving an air-sprur automatic-transmission rea engined bus for the first tin (that was a General Moto vehicle) experience the value Ford'stilt-cab, and the horro of American brakes of that er 62ft from 30mph at 9 tons gv‘ and complete brake fade aft the third stop!

An essential for any CM test in those days — and I cover€ the period from early 1 954 mid-1964 — was to be ei thusiastic, fit, prepared for or hours and periods of extrerr frustration — and preferabi young. More often than no passenger-vehicle tests wer carried out in bare chassis fon (the vehicle, not the tester), an this made me a staunch advi cate of integral construction as means of getting a bodie vehicle for test.

Albion, a company of hard Scots, often provided eve goods vehicles for test without cab. With many makes of cal there was little comfort in an case — draughty, unheatec mped and noisy. If the )ther was good, you were ter off without a cab, and n the manufacturer's viewnt it also meant that you ildn't criticise the cab's all many weak points.

Vehicles changed quite a lot ing my years at CM. Gross ghts started to go up, speed its were eased, and the iicle designers were dragged (ing and screaming into the :ond half of the twentieth itury. When I started testing CM, most vehicles had the Clayton Dewandre vacuum:isted mechanical brakes, ile power-assisted steering s an unnecessary luxury (and l't forget that a six-wheeler I a 6-ton front-axle loading). Engine powers slowly started go up, maybe as a result of , continued carping about cierpowered vehicles, so at t we started to get reasonably od road performances, and thout the reduction in fuel )nomy that the operators who int for low power:weight ios feared. Cabs got better, mparatively, with fewer )ughts, lower noise levels and )re frequent fitment of aters. Significantly also, the od of high-quality imported hides was starting to get der way — a flood which the itish makers have not been le to stem.

Were the CM tests useful? If 3nufacturers' and operators' mments were anything to go , the answer is yes, because ?.y certainly attracted a lot of :ention. Observations made in a test reports often resulted in anges to vehicle specificains being made or useful ()pins being introduced, while as as the potential buyer was ncerned the tests gave a good sight as to whether the vehicle 3s anything at all along the ies that they had in mind for eir next purchases. This even )vered such specialised !hides as cesspool-and-gulley nptiers, street sweepers, fuse collectors, ambulances id fire appliances.

Vehicle life was something at could not be indicated, her than if an actual failure :curred in some vital area — -id such things did happen Dm time to time. If a manufacirer was prepared to put a degn change into production, the ist report's publication was metimes delayed so that ie change could be assessed, it otherwise the vehicle's chaicter was reported in full — arts and all.

Breakdowns were not infre quent. I remember the gearbox of an AEC Marshal 6x2 opening up like a clamshell while attempting a reverse restart on some rough ground near Dunstable, and being stuck there for about six hours on a chilly spring night (production vehicles had a different design of box). Austin trucks seemed doomed often never to complete the course, whilst I will always recall crossing a busy road junction in the 'Manchester area in a Seddon 24-ton artic that had just lost its brakes. Loose test loads were another hazard, as were the police in the days of 20mph speed limits.

We did sometimes have to bend the law a little. I remember doing 67mph with an Albion Royal Scot 17-ton six-wheeled bus chassis on a road in the Stirling area for example, and I'm sure the Seddon Sirdar's 31.5 tons gvw would have been regarded as illegal had we been directed to a weighbridge; since this was a six-wheeled rigid and the year was 1959!

Maybe there would have been advantages to using the MIRA test track, but even though the "opposition' — Motor Transport — was using it, I still elected not to, mainly because of the time-saving and vehicle-availability advantages made possible by local testing. We would sometimes use disused airfields if one was near enough, as when testing the Scammell Constructor at 84 tons gtw, while the FV R DE (as it was then known) test courses were used as appropriate. Even so, the heaviest outfit I tested — the Rotinoff Atlantic 103-tonner — was kept to public roads.

• Talking about the FVRDE, the Chobham rough courses were great fun to use, and it became traditional to get photographs of any vehicle we tested there with all its wheels off the ground. This wasn't too bad with light stuff like the Land-Rover, Gipsy and Jeep (although I did bend a Land-Rover front axle once), but the Thornycroft Nubian 6x6 was a challenge at 12.65 tons gross, as were the Leyland / all-wheeldrive and Volvo 4x4s; the leyland and conversion, but the way, was the first heavy wheeled vehicle to get to the top of tyhe FVRDE's M:1.73 (30') test slope.

One road-test innovation instituted during my -reign" — the credit being due to John Savage — was the maintenance test. The object here was to carry out various routine tasks such as oil-level checks, injector removal and replacement, brake

adjustment and wheel changes, all according to the driver's manual and all against the stop watch. It would have been great to have had just one vehicle with tilt cab and self-adjusting brakes and a spare-wheel winch . . .

But all in all it was fun being CM's technical editor and doing something like 30 tests a year. But these days I prefer to curl up by the fire and read what the new generation is testing.

JOHN MOON referred to strenuous routines and the need for CM testers to be enthusiastic, fit and prepared to work longer hours. He was right. My first experience of a Commercial Motor road test was quite shattering. I was shown the van-test procedure by John on an Austin J4 van and never realised that so much complicated work could be compressed into one day.

That was in late 1960 and as the assistant, all the light vehicles were mine. It did not take so long to get into the routine, or to find that it was a pretty good road test system. The important thing was to minimise the variables — use the same test circuits (if you could) for the short-distance fuel checks, maintain similar running speeds, always drive with the same technique.

Provided this was done on the series of fuel consumption runs — there were seven for the light vehicles including full and half load and empty and with one and four stops to the mile — you could get an acceptable comparison from one vehicle to another. That was what it was really all about — comparisons. The same applied to heavy tests too which I took over when John left in 1964. Here it was more difficult though as unlike the vans and pickups, it was still considered impracticable to bring the heavies from factories all over the country to be tested over the same ground — all testing including acceleration and braking was, of course, still done on normal roads.

Fortunately, the areas developed over the years, strategic to the UK maker's premises, allowed this — without danger in the case of braking — but the build up in traffic in the 1960s brought the problems for the heavy tests. Fuel consumption checks had to be re-runi more often than not through baulking by slow traffic, expeciaily on the high-speed motorway tests when hgv were knocked off the third lane.

It became almost impossible to do brake tests, so something had to be done. Fortunately, it was not difficult to find a solution as Ron Cater and I had been working on the idea of starting up long-distance road tests for the heavier vehicles. We had the example of the extended test runs in the earlier years but the objective now was to get to a practical exercise that would enable comparability to be maintained and at the same time have a route that met a number of other parameters.

It had to go past MIRA where a stop could be made to do brake and acceleration tests, it had to be a severe test on the vehicle including all types of running and with severe as well as long hills where climb times could be taken, it had to be like a real trunk run, at least for the main part, to which readers could relate and which would enable real fuel consumption and average speed figures to be taken.

There were other aims and I believe we found a near perfect route. The decision was to go to Scotland and back and as this was in the relatively early days of motorway construction, well before the M6 was completed, the initial route was by way ol Ml, A5, M6 to its end, then at Carnforth. Then came the first really interesting bit — A6 through towns like Penrith and Kendal and the "romance" of climbing Shap to Carlisle.

Perhaps there we deviate0 from the "trunk route" pattern. We did not take the "direct" route to Edinburgh which WE were aiming for as the start oi the run "home" but we felt thE A74 and the route over thE Tweedsmuir Hills via Moffat was valid and more interesting. From Edinburgh — or near it, Dalkeith — the real hard stuff started — A68 which is probably the most severe "trunk" route in the UK — and a good main link with A1, then M1 back to the start.

It was a good route and remained so despite the changes made in my time with the extension of the M6 to Carlisle and so on; it would have been "nice" to retain the interest of Shap and A6 but it would have been out of line with the desire of a valid trunk run.

After the decision on the final pattern of the route, it was put into practice with a vehicle which looked to be a design for the future — the AEC V8 Mandator. There was no dummy run. I was planning to get to a two-day exercise but on this first occasion, three days had to be allowed with set tests at MIRA and overnight stops at Preston and West Woodburn.

The party on the test included John Dennis and Jay Cooper of AEC (now with Volvo and Fiat respectively), AEC's driver, Arthur Holland, and Ron Cater and myself — with Dick Ross taking the pictures. And it worked. There were just one or two snags, like getting lost a couple of times — and pulling apart a brake coupling hose when turning the outfit round on one of them — but apart from this, the route turned out to be just right and what was very important with the pressure on time, it was feasible as a two-day run, with an overnight stop at Pathhead near the turn-round point.

Sometime later, the Midlands route was developed for medium-weight vehicles — this time with the help of Ron Carl, BMC's head of truck testing and that also proved successful but various ideas of developing operational-type tests for light vehicles were considered impractical and it was decided that the long standing method was continued — I still think the series of duel consumption tests with alternative stopping patterns and varying payloads, plus using the vehicle as personal transport for a period enables a pretty good assessment to be made of a light vehicle's performance and character.

After we introduced the long-distance operational-trial type of test, other publications followed and this was a natural development. Things had changed so much since the late Fifties to alter the pattern of road transport — largely the development of motorways — that it was important to see how vehicles performed in the new enviroment. We lost a number of features of the previous tests, the important ones being loss of brake-fade and unladen tests. Brake fade was not a real loss though as technology had improved so much that no vehicles gave bad results on short-hill descent fade tests. Unladen checks were different. It is surprising how many lorries were —and still are — terrible when driven empty with oversensitive brakes, harsh suspension, imprecise stearing, etc; I wonder how many vehicles would have load proportioned braking on driving axles only if Press testers did empty tests!

But the losses were amply repaid by the advantages of the new type of test. In particular, the 750-odd miles made the tester tired and put him in the same situation as a regular driver. In the days of barechassis tests, regular longdistance runs would not have been possible or particularly relevant, but now all tests were of cabbed and bodied trucks. Designs had also improved enormously so more involvement with the vehicle was needed to make valid assessments. Initially the improvements in designs must have been helped by awareness of higher standards in Continental vehicles through such things as CM tests of European vehicles but then the Continental invasion really got under way and accelerated the improvements.

It seemed that most heavy

vehicle tests were of non-Briti models, but then the Contine tals were putting the pressu on to get in the market — regretted very much that in my time doing road tests, never had the opportunity trying out an ERF — and I test. only one Foden. Most of ti problem was availability vehicles in a seller's market b there was over concern at finding weaknesses. Such da had passed though. Vehicl had improved enormously al inherent defects were rare. TI last I was involved with were tl discovery of art important err in front suspension / steerir geometry on the initial Fo D100 tractive unit whic caused deviation when brakir and BMC FJ transmissic weaknesses.

Parts broke on some of n tests — a prop shaft on a Scan on a test in Sweden, and BlV FJ diff. on hill-climb tests, tl reverse gear train on an SR automatic gearbox doir reverse 1 in 6 hill restarts MIRA, but I never had to aba don a normal road test apa from these. In fact most of tltroubles I had occurred wi• 4x4s at FVRDE / MVEE at Ba shot Heath and Chobham — broken prop shaft when doing dynamic hand-brake -test ar water sucked into the engir when doing "the water splash were two examples. A whe came off when being towE after the last incident but th was not really the vehicle's fat, — I should have checked a wheel nuts after doing tl45mph test on the very sevei MVEE pave and the battering c the Bagshot Heath test ground There is a certain amount ( danger when testing at MVE and I certainly felt this whe making my first decent of the in 1.73 slope (like going ov( the edge of a cliff) and eve more when I was climbing tl-t

slope in a Lond-Rover when full cut out as I was right at the to — it took me some time to pic

up enough courage to decid that I had to get the vehicl

down myself and even more t do the actual getting down. Bi perhaps my worst time ther

was in an Austin Gypsy doin the "wheels of the ground" b referred to by John Moon. M technique was to select a geE. with the right speed at fu

throttle than jam myself into th seat with the left foot pressin against the floor corner near th clutch, the other on th

Christmas road tests of old commercial vehicle have been a popular feature in CM for many years now. In 1971 Gibb Grace tested the accelerator pedal and with sti 1915 Peerless TC4 4-ton chassis with pick-up body and found that the public actually liked old lorries. A legend on the chassis says arms on the wheel to keep m top speed is 12mph. but Gibb got 20mph out of it. continued overlo ck against the padding. This :he only way to keep control at out 20/25 mph on extremely it-holed surface up to and yond the "triple jump." With a Gypsy it all went perfect rtil after the "jump.I took my at off the accelerator and sudntly realised I was not slowing iwn — the throttle linkage d stuck wide open. Having eased my "jammed-inposin, I was being thrown about e a pea in a barrel, fighting to t to the key to switch off the gine and my feet on the clutch d brake whilst steering to oid the worst of the bumps. rtunately I managed to stop ,fore reaching a clump of !es.

Despite this, it was great fun, it then this could be said about Jch of the road testing, and are than this, it was extremely .eresting, especially getting to ow intimately the qualities d idiosyncrasies of the model. le only time it was not fun was len there was evidence of ally bad design — of skimping save pennies on important ms — of lack of attention to ;ulation against noise and to spension to improve ride — of thing done to minimise driver igue. In such cases the biggt wish was to have the deFier responsible in the cab ;o so that he could taste the lit of his "labours."'

Gib Grace loos pack

IAD MET Tony Wilding while irking as technical editor of itomotive Design Enleering magazine, but never agined I would follow him on g. I had an automotive backaund with Ford, Rootes and uxhall and had written up CVs ring my time with ADE, but I never driven one. But I need not have worried, for Tony gave me a lightning tour of the British manufacturers and went with me on my first road test, and I soon passed my hgv test, thanks to the RTITB at High Ercal.

The Scottish route that had been established in Tony's time rapidly became recognised by the manufacturers as the route to be tested over and with 32 tonners becoming increasingly popular; there was no lack of test vehicles. In my first year, I tested ten 32-tonners and got to know the top end of the M6 and the A68 almost as well as my journey to work. The route remained largely unaltered over a number of years, allowing sensible comparisons to be made, but, inevitably parts of the route changed.

For example, the original route took the old A6 through Shap, and on up to Gretna Green, but switched to M6 as soon as it opened. ln fact, I. never did drive over that part of the original route. A number of small changes on the A68 such as widening and straightening the road must have improved journey times, and fuel consumption over the years, but it is impossible to say by how much.

When the M6 Midlands link to the M1 finally opened, there was much discussion as to whether the road test route should leave the A5 and take the M6, but that was one part of the old route which has stayed even up to now. I was often asked if I thought the route was too long, or if it included too much motorway, but I thought then as I still do, that it is about right. Thirty-two tonners spend a lot of time on motorways, and 450km (281 miles) in an eight-hour driving day is becoming the norm for many trunkers.

The vehicles in my time, 1970-72, were mainly second generation vehicles and the mechanical failures mentioned by John Moon and Tony Wilding were all but unheared of. During my time vehicle performance was improving rapidly, and the emphasis was in more accurate and meaningful testing.

Perhaps the most basic requirement of any test route and yet one of the hardest to achieve is a simple distance measurement. Route maps give some distances, but never the ones you want, and vehicle mileage meters all differ no matter how well they are checked. So we had a special electric instrument made up which we could tow behind a car and measure up the route once and for all. This "'bicycle wheel'' mileometer worked a treat, and for the first time, we had distances between fill-ups exact to 0.1 of a mile.

For accurate fuel consumption testing the other variable is the amount of fuel added at the end of each stage, and this we decided was most accurately done by dividing the price of the fuel added by the price per gallon. This gave us the fuel added with an accuracy of better than one per cent.

The one problem we could never get over — and I guess this still applies — was being certain that the tank was refilled to the same point. Often this was impossible because of the fall of the filling station forecourt either across the vehicle, or from front to rear. The only reliable fuel consumption therefore was the overall result for the whole route and those taken on a level track at specific speeds at MIRA.

Competition among the manufactures grew and I soon realised that fuel consumption was only one aspect of vehicle performance. Journey time and payload were almost as important and, obviously, affected the overall efficiency of the vehicle. The problem was how to equate a vehicle X that achieved 6.7mpg at 39mph carrying 20.6 tons for example with a vehicle Y achieving 6.5mpg at 41mph, carrying 21 tons, and come up with a "best performer." The concept of ton miles of payload per gallon' was already well established and I simply added the third factor of speed to give ton miles per gallon per hour. In the example above vehicle X has a factor of 5.382 and vehicle Y has a factor of 5.526 showing it to be the better of the two.

This efficiency factor as I called it proved to be a powerful analytical tool and made meaningful comparisons very easy, and I used it in one "Tester's Twelvemonth'' article to rate all the vehicles tested that year. Looking back now, it could well have been CM's first comparative test. Up until my time at CM, test vehicles were hard to come by and for the operators it was largely a sellers market. However, the picture has changed and, with the influx of large number of imported vehicles to become a buyers market. With so many makes competing, the reader expects a journal to compare the various makes and select a best buy.

We certainly made a start on this 'group testing,' as it became known, during my time at CM. One Sunday morning, the entire technical staff, with their wives and girlfriends turned out to test a series of light vans around a route which the assistant technical editor set out in North West London. We had a good time — and we had lunch on CM!

Apart from testing all sorts of vehicles in the UK, ranging from a Lacre road sweeper to Renolds Boughton airport crash tender, I made several trips abroad and experienced the competition and export territories at first hand. I visited Morocco and drove locally produced Volvos, Italy to drive Fiats, Germany to drive Mercedes Benz, Holland to drive a DAF, Sweden to drive Volvos and Scanias, and France to drive Renault and Berliet.

I was one of the few British journalists at the time to visit Berliet and I was most flattered when their Public Relations man Rene Rolland arranged for me to drive their new 350 bhp V8 and their PR 100 city bus. I was OK with the truck but, managed to get into one or two tight squeezes with the bus in the narrow streets of Lyon's old quarter.

The importers were really beginning to make inroads into the British market in my time with CM and it hurt — it was easy to see why. The British manufacturers had been largely left behind as regards ride and driver comfort and in vehicle performance, and it was difficult to see how to stop this influx let alone redress the balance.

Looking back now, it is easy to spot a major omission of our road testing and reporting at that time, and that was in assessing service costs and parts costs. For many operators who were originally tempted to buy foreign because of low initial prices, have since been disappointed by the short service life of some parts, and their high replacement cost. My two and a half years at CM were over all too quickly — I often think what it would have been like to have stayed on and written about the renaissance of the British truck.

Graham Montgornerie looks ahead.

WHEN I joined CM in October 1973 I made an immediate impression. The following month the journal closed down for four and a half months due to a printing dispute. Not my fault admittedly but hardly an auspicious beginning. At that time it was possible to predict with surprising accuracy the fuel consumption of a 32tonner around our famous Scottish test route. Although Gibb Grace had recorded a resounding 7.5mpg with an 8LXB engined Atkinson in 1973, the norm around that time was nearer the 6.5 mark.

It was not until the 1626 Mercedes-Benz was tested that the seven mpg barrier was broken again but it was still a long way short of the Gardner's performance. In 1977 we began to see the start of the trend towards greater fuel economy among the manufacturers. Not that they had been neglecting this important aspect of vehicle performance. Far from it. The fact remains, however, that it was only in 1977 that we began to see evidence of the work that the engine and vehicle manufacturers had put in.

By the time that the original Scottish road test route was superseded in late 79, the bench mark had been pushed up to 7.5mpg with several on or above the magic figure of eight.

The first unit to improve upon the Atkinson/Gardner figures was the DAF2300 and it did so in no uncertain manner returning 7.9mpg. It was on the slow side, however, completing the 700-plus mile test route only half an hour quicker than the Atkinson.

A few months later we had the first of the Cummins E290 engined chassis and this combined the economy of the DAF with a much faster journey time.

What with the OAF DHU 825, the L versions of the RollsRoyce Eagle range and the Big Cam Cummins, the engine manufacturers made giant strides in the period 1973 to 1978.

When we started publishing again in March 1974, it was a convenient time to introduce metrication into the journal. With the increasing number of continental marques entering the UK in that year, all specified in metric units (or partly metric — but come back to that later) it was also more logical. It did raise a problem however, in that, for many people, a complete overnight switch to metric units would have caused unnecessary confusion. Hence our dual system where we quote, for example, the wheelbase as 3.5m (lift 6in).

I had hoped back in 1974 that by the end of the Seventies the industry would have gone completely metric and this emabled CM to drop the old Imperial units. However the country in general had dragged its feet over the whole subject of metrication — indeed the oftquoted joke that -the UK is going metric inch by inch" has more than a hint of truth of it.

To give an example of the prevarication that is still going on over metrication, there is one major vehicle manufacturer in the UK who quotes engine power in kilowatts and wheelbase in inches!

One feature of the CM road tests which I introduced in 1975 was the use of graphs and histograms in the presentation of the test results. When quoting speeds in gears, for example, it became very tedious and difficult to read a long string of numbers after we adopted our dual standard for units. This we switched over to "visual aids" with the first road test of the Seddon Atkinson 400-Seri' back in 1975.

Also introduced at the sarr time was a series of compa isons between the test vehicle question and four of its cor petitors. This compared variot aspects of vehicle performary including fuel consumptioi braking distance and (her, acceleration time from rest • 40mph. Although it was alwa, a panic to get the results numbers transferred to results drawings within the confines , printing schedules. I thought presented the test figures in more readable form.

It was during my "period office'' as technical editor thi our traditional brake test equil ment ie the chalk gun WE replaced by a Motomete Although the chalk gun WE ommendably simple in priniple, it was something of a nuiance in practice. So many eople used a chalk gun at IIRA that trying to find "our'. halk mark was somewhat akin 3 finding the needle in the aystack.

The Motometer is a very exensive piece of equipment but, part from the convenience spect, it has two very important dvantages over the chalk gun a permanent record of the est results on the chart and a leasure of the pedal effort reqired. The trace on the chart also nabled us to examine the raking -character."

The chalk gun gave the disvice and the mean efficiency ut with the Motometer it was ossible to see whether the raking efficiency was constant II the way through or whether )ere was an initial peak which Ipered off — and soon. Veri, efinitely worth the money.

Talking of expensive pieces f test equipment, the ultimate as got to be our 40ft Crane ruehauf test trailer. We took elivery of this in late 1977 and was used first on the record reaking DAF 2300 test.

There were a number of reaons for having our own trailer. he most obvious one was that .f consistency as we could use le same trailer (legal dimensioal requirements permitting) iith every tractive unit. As we ad had a number of horrifying xperiences in early road tests lue to poor maintenance on the nanUfacturer.provided trailers, ve were anxious to bring trailer 'reparation ''in house" as it vere. Now Crane Fruehauf indertakes all trailer inaintelance so when we start a test we now we can concentrate on the ractive unit without worrying ibout the trailer.

One test, which departed rom the norm as far as the UK was concerned, took place in early 1975 with a Volvo F88 at both 32 and 38 tons gross — with special dispensation at the latter weight. This test was to provide some information on the improvment in productivity when running at higher weights — based on actual tests results and not merely on speculation.

The end result was a 28 per cent increase in paylaod capacity balance against a fuel penalty of 11 per cent. That was in February 1975 — and at what gross weight are we running now?

Steve Gray says:

That is how Commercial Motor's road test programme began. Prior to that we were dependent on tests carried out by the Royal Automobile Club. Throughout the 75 years our tests have been recognised as being authoritative — and still are. As each successive technical editor has taken over responsibility for the tests, he has adjusted his methods to meet the demands of the operator.

Long before the days of fast trunk roads and before the plans for the motorways reached the drawing board, we were road testing vehicles in operating conditions. As these conditions changed so did our road test procedures.

Today we have three separate routes — one for local delivery, light commercial vehicle operation, another for medium haulage routes; and the third for our long-distance trunk route.

As the motorway routes have extended so has our trunk road test route. It now takes us from the Midlands well into Scotland.

We simulate conditions which operators might expect over any surface, camber or incline at the Motor Industry Research Association (MIRA) test ground, and even for tipper operation we have a special proving ground and route. An example of this arduous test will be published in April.

CM's tests are carried out objectively and where we find what are in our opinion serious defects, these are discussed with the manufacturer and our queries and their answers are published.

The purpose in all of our road tests is and always ha5 been to provide the operator with information so that hE can make fair comparisont between makes and modeh over as near as possible iden, tical routes in identical circumstances.

It must be appreciated that we run the vehicles within thE legal weights, dimensions and drivers' hours, and in futurE we will produce the tacho• graph records of the vehicle we have road tested.

I would appreciate an communication which wil help me to develop my roac test programme for the great est benefit to our readers.