Full Marks for thi dark 14

Page 46

Page 47

Page 48

Page 49

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

By John F. Moon,

A.M.I.R.T.E.

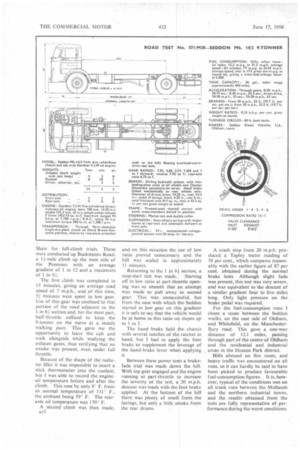

ALTHOUGH. representing an interesting departure from previous Seddon design practice in respect of power unit and braking, the Mark 14/3 maximumload four-wheeler continues the tradition of simple chassis layout in the interests of reliability and economy. Despite its simplicity, the design is progressive, incorporating such recent developments as an airpressure servo braking system and part-Plastics cab.

Its road performance, verified after a two-day test in the hilly Oldham area, is most satisfactory. The Gardner 5LW oil engine provides sufficient power for all normal mainroad gradients to be taken at reasonable speeds, and the braking system, with its efficient and rapid response, sets a new safety standard for vehicles of this weight.

The Mark 14 range consists of three models: a 14-ft. 6-in.-wheelbase version for goods (the model chosen for the test); an 11-ft.-wheelbase tipper, and an 8-ft. 6-in.-wheelbase prime mover for use at 20 tons gross vehicle weight. Two power units are offered, the Gardner 6LW 112 b.h.p. engine being available as an alternative to the 5LW 94 b.h.p. unit as fitted to the test chassis.

Although the use of the 112 b.h.p. engine is recommended primarily for the 8-ft. 6-in.-wheelbase model, it can be supplied with the long-wheelbase chassis when it is required for operation with a trailer or in exceptionally hilly areas. For all normal use in Great Britain as a solo machine, the 5LW unit provides ample power.

A David Brown four-speed or fivespeed gearbox can be supplied to a 1 2

order, both units having direct-drive top-gear ratios and the four-speed box a 6.6 to 1 low-gear ratio. An Eaton 18,500 two-speed axle, with 4.5 to 1 and 6.14 to 1 ratios, can be ordered as an alternative to the standard overhead-worm-drive axle. The single-speed axle is offered with alternative ratios of 5.5 to 1 and 6.75 to I. The standard unit has 71-in. centres, but for use under arduous conditions an 81-in.-centre final drive is fitted.

For operation in areas where no serious inclines are likely to be encountered the 74-in., 5.5 to 1 axle should be sufficient, with corresponding improvements in fuel-consumption rates over those obtained during my tests with a 6.75 to 1 axle. Even better figures would be returned from the use of the Eaton two-speed axle and the wide-ratio four-speed gearbox.

Girling hydraulic brakes are fitted as standard, with two-leading-shoe units on both axles. The Clayton Dewandre concentric air servo acts quickly and powerfully; indeed, during the emergency brake applications, the front weight penetrated the headboard of the test body_ Although fierce during emergency conditions, the brakes are fully progressive, and this system provides all the power of a full air-pressure circuit, but with reduced delay and weight. In the unlikely event of the air pressure failing, it would still be possible to brake the vehicle by applying the pedal without servo effect.

The contemporary and praiseworthy trend towards better driver comfort is well in evidence in the cab of the Seddon Mark 14. Large, curved windscreen panels and rear quarter lights contribute towards glass-house visibility in all directions. although even better vision under all conditions would be possible were twin windscreen wipers and driving mirrors to be fitted as standard. Both cab seats are of the bucket type, giving full support laterally and rearwards, and the driving seat is adjustable vertically and horizontally.

There are two ashtrays in the cab and polished wooden fillets add an air of well-being. Ventilation is provided by hinged vents in the loaf canopy above the windscreens and the test vehicle was equipped with an optional recirculatory heating and demisting system.

In design, the cab is interesting by reason of the extended use of plastics panels.. The roof panel, for example, is a one-piece moulding, and the rear one is fabricated in like manner. Plastics is used also for the front quarter panels and, on some cabs, for the doors. This increased use of glassfibre reinforced resin is fast becoming a feature of all Seddon bodywork and saves time, weight and money.

The test chassis was straight off the

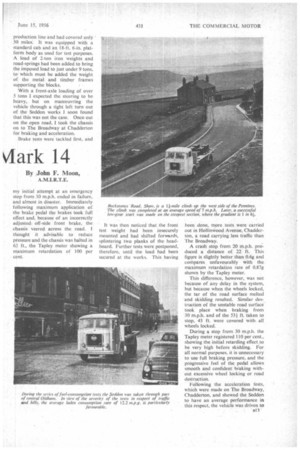

production line and had covered only ' 50 miles. It was equipped with a standard cab and an 18-ft. 6-in platform body as used for test purposes. A load of 2-ton iron weights and road-springs had been added to bring the imposed load to just under 9 tons, to which must be added the weight of the metal and timber frames supporting the blocks.

With a front-axle loading of over 5 tons I expected the steering to be heavy, but on marneuvring the vehicle through a tight left turn out of the Seddon works J soon found that this was not the case. Once out on the open road, I took the chassis on to The Broadway at Chadderton for braking and acceleration.

Brake tests were tackled first, and

my initial attempt at an emergency stop from 30 m.p.h. ended in failure, and almost in disaster. Immediately following maximum application of the brake pedal the brakes took full effect and, because of an incorrectly adjusted, off-side front brake, the chassis veered across the road. I thought it advisable to reduce pressure and the chassis was halted in 63 ft., the Tapley meter showing a maximum retardation of 100 per cent.

It was then noticed that the front test weight had been insecurely mounted and had shifted forwards, splintering two planks of the headboard. Further tests were postponed, therefore, until the load had been secured at the works. This having been done, more tests were carried out in Hollinwood Avenue, Chadderton, a road carrying less traffic than The Broadway.

A crash stop from 20 m.p.h. produced a distance of 22 ft. This figure is slightly better than 0.6g and compares unfavourably with the maximum retardation rate of 0.87g shown by the Tapley meter.

This difference, however, was not because of any delay in the system, but because when the wheels locked, the tar of the road surface melted and skidding resulted. Similar destruction of the unstable road surface took place when braking from 30 m.p.h. and of the 53+ ft. taken to stop, 43 ft. were covered with all wheels locked.

During a stop from 30 m.p.h. the Tapley meter registered 110 per cent., showing the initial retarding effect to be very high before skidding. For all normal purposes, it is unnecessary to use full braking pressure, and the progressive feel of the pedal allows smooth and confident braking without excessive wheel locking or road destruction.

Following the acceleration tests, which were made on The Broadway, Chadderton, and showed the Seddon to have an average performance in this respect, the vehicle was driven to

Shaw for hill-climb trials. These were conducted up Buckstones Road. a 14-mile climb up the west side of the Pennines with an average gradient of 1 in 12 and a maximum of 1 in

The first climb was completed in 15 minutes, giving an average road. speed of 7 m.p.h., and of this time, 5i minutes were spent in low gear. Use of this gear was confined to that portion of the road adjacent to the 1 in 63 section and, for the most part, half-throttle sufficed to keep the 9-tonner on the move at a steady walking pace. This gave me the opportunity to leave the cab and walk alongside while studying the exhaust gases, thus verifying that no smoke was present, even under full throttle.

Because of the shape of the radiator filler it was impossible to insert a stick thermometer into the coolant, but I was able to record the engineoil temperature before and after the climb. This rose by only 8 F. from its normal temperature of 131° F, the ambient being 59° F. The rearaxle oil temperature was 170° F.

A second climb was then made, 1111 and on this occasion the use of low ratio proved unnecessary and the hill was scaled in approximately I I minutes.

Returning to the 1 in 61 section, a stop-start test was made. Starting ofT in low ratio at part-throttle opening was so smooth that an attempt was made to pull away in second gear. This was unsuccessful, but from the ease with which the Seddon started in low gear on this gradient it is safe to say that the vehicle would be at home in this ratio on slopes up to 1 in 5.

The hand brake held the chassis with several notches of the ratchet in hand, but I had to apply the foot brake to supplement the leverage of the hand-brake lever when applying it.

Between these power tests a brakefade trial was made down the hill. With top gear engaged and the engine running at part-throttle to increase the severity of the test, a 20 m.p.h. descent was made with the foot brake applied. At the bottom of the hill there was plenty of smell from the facings, but only a little srke from the rear drums. A crash stop from 20 m.p.h. produced a Tapley meter reading of 58 per cent., which compares reasonably with the earlier figure of 87 per cent. obtained during the normal brake tests. Although slight fade was present, this test was very severe, and was equivalent to the descent of a similar gradient four to five miles long. Only light pressure on the brake pedal was required.

For the fuel-consumption runs I chose a route between the Seddon works, on the east side of Oldham, and Whitefield, on the ManchesterBury road. This gave a one-way distance of 12.1 miles. passing through part of the centre of Oldham and the residential and industrial areas in the Heaton Park district.

Hills abound on this route, and heavy traffic was encountered on all runs, so it can hardly be said to have been picked to produce favourable fuel-consumption figures. It is, however, typical of the conditions met on all trunk runs between the Midlands and the northern industrial towns, and the results obtained from the tests are fully representative of performance during the worst conditions. Each fuel-consumption test consisted of out-and-return runs, making a total distance of 24.2 miles, and laden and unladen tests were conducted, a calibrated test tank being used for maximum accuracy. For the unladen runs the battens and brackets supporting the test weights were left on the body, bringing the uhladen weight up to more than it would be with a normal-length, timber, drop-sided body.

The laden run out to Whitefield was made at an average speed of 22.4 m.p.h., despite the heavy town traffic met in Oldham and the fact that the maximum speed was rarely allowed to exceed 30 m.p.h. Seven traffic stops were made, but the fuelconsumption rate worked out at 13,6 m.p.g. The return run was slower because of steeper inclines. Including four traffic stops, it was completed at the average speed of 20.2 m.p.h. and 10.8 m.p.g. was returned.

With the test load removed the outward run was made at an average speed of 215 m.p.h. and a consumption rate of 21.4 m.p.g., eight stops being necessary. The return trip produced an average speed of 23.8 m.p.h, and a 16.6 m.p.g. consumption rate, with four stops over the 12.1-mile distance,

From the averages of these figures it will be seen that any operator running the Seddon Mark 14 with a payload in only one direction can expect a normal fuel-consumption rate of 15.5 m.p.g. under the most unfavourable conditions.

Freedom from Fatigue Having driven the vehicle for nearly 100 miles during these tests, I am satisfied that it should not prove tiring for drivers on long trunk runs. With the exception of the heavy throttle pedal. all the controls are light in operation and well placed in relation to the driving seat. The gearbox has a particularly pleasant action, and the ratios are well matched to the engine torque curve.

Engine noise is not unduly pronounced, and at all times the power unit runs smoothly. no vibration being transferred to the cab or chassis frame because of the resilient mountings and damping member.

At the conclusion of the roadperformance tests I returned the Mark 14 to the Seddon works to carry out a series of maintenance tasks. The first of these was to adjust the brakes, and for this I used a trolley jack which enabled me to jack up both wheels and each axle simultaneowly.

There is a single adjuster on each back plate, making these brakes among the easiest I have ever had to adjust, besides being the most effective. Both rear brakes were adjusted in 1 minute 23 seconds, whilst the front units were set in I minute 22 seconds, these figures including the time taken to raise and lower the wheels.

Level checks followed, and that of the coolant in the radiator was verified in 6 seconds, a snap-fastaning filler cap greatly easing matters. Because the engine dipstick is located to the rear of the crankcase it is unnecessary to remove the engine cowl to reach the stick, access being possible from the rear of the cab. It is possible to check this level in 15 seconds, and while at the rear of the cab I inspected the oil level in the gearbox in 40 seconds, a dipstick being combined with the filler-orifice nut on this unit,

There is a combined filler and level plug. in the rear-axle casing, and the oil level was checked in 35 seconds. The oil-bath air cleaner is below the cab floor in the near-side front corner. The oil bowl, which is retained by a ring and two wing nuts.

was removed and replaced to check the oil level from underneath the chassis in 3+ minutes.

Because the cross-bearers of the test body did not coincide with the cross-bearer positions of the standard body I was unable to remove the lid of the battery box. With the correct body mounted, however, no difficulty will be experienced in attending to this important equipment.

A paper-element fuel filter is included in the fuel system, between the fuel tank and the lift pump, and is located on the near-side frame member, close to the cab. I removed and replaced the filter element in rn inutes.

The works closed for the week-end before I could carry out tasks on the power unit, but I was satisfied that the engine and its accessories could

easily be reached with the cowl removed. This cowl is in three sections—the two sides are each secured by two spring clips and the top section retained by four bolts. A useful feature of the top cowl panel is a small hinged trap at the near-side front which gives simple access to the engine oil-filler cap.