VAUXHALL ASTRAVAN 2.001

Page 28

Page 29

Page 30

Page 32

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

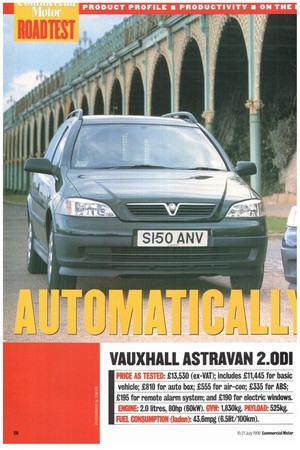

IPRICE AS TESTED: £13,530 (ex-VAT); includes £11,445 for basic vehicle; 1810 for auto box; .1555 for air-con; 1335 for ABS; 1195 for remote alarm system; and £190 for electric windows. ENGINE 2.0 litres, 80hp (60kW). GVIV: 1,830kg. PAYLOAD: 525kg. FUEL CONSUMPTION (laden): 43.6mpg (6.51it/100km). Now CM has had a chance to test Vauxhall's auto Astravan over three months, many of the myths associated with automatics have been dispelled. It's not just for the lazy or senile, either... A D utomatic transmissions—they're slow,

inefficient and can never decide which gear they ought to be in. Right? And as for fitting one to a diesel van, in the words of the immortal Bard of Wimbledon, "You cannot be serious". Well maybe, not so long ago, all that might have been true. But that was when the automatic gearbox lived in a world of its own, with the only inputs being road and engine speeds, and a kickdown cable which had inevitably stretched out of adjustment after the first week. A device that invariably deserved the name "slush pump" even when fitted to the back of a nice big, torquey petrol engine. When attached to a small diesel engine— well, the words "black cab" say it all, really

So what's changed today? For a start, the common or garden automatic transmission got smart and started to communicate with the engine (or more specifically, its electronic management system). While the fundamental method of operation, a set of epycyclic gears controlled by hydraulically actuated brake bands, is much the same as it was between the wars, easy access to an electronic wealth of mechanical and environmental data means that the gearbox can now respond to all kinds of criteria. The more advanced examples even use something called "fuzzy logic", which can learn a driving style at any given time, whether lazy or sporting or something in between, and adapt the transmission characteristics accordingly

Even quite basic systems now have at least four forward gears, with the ability to lock up the torque converter in higher gears, preventing the slippage that is otherwise inevitable. Many also have alternative modes of operation, allowing the driver to choose between optimal fuel economy or performance on demand. As for the small diesel engine, you won't need reminding of that sector's advances in power and refinement in recent years.

When CM first encountered the Astravan turbodiesel auto at its launch in the Yorkshire Dales, we naturally approached it with an open mind, at the same time being fully prepared for all the old prejudices to be confirmed. But before you could say "Emmerdale" we realised we'd stumbled on to something really rather good. It was immediately apparent that Vauxhall's mating of its torquey 16-valve direct-injection turbo-diesel with the smooth-shifting auto box was a winning combination.

But giving the left foot an hour's break on a press launch is one thing; operating an automatic in the real world might be a different matter altogether. The only way to be sure would be to live with it for an extended period, so when a vacancy arose at CMfor a long-term test van, Vauxhall agreed to fill the gap. Accordingly, on April Fool's Day we received a dark blue Astravan LS 2.00i 16V complete with automatic transmission, ABS, electric windows and air-conditioning.

Product profile

Available with the 1.6-litre petrol and the 2.0-litre turbodiesel engines, the transmission is a four-speed electronically controlled unit with three modes of operation.

The default is "economy" which, as its name suggests, adjusts the gearshift points to optimise fuel consumption. Pressing the button marked "S" on the control lever engages "Sport" mode which, by forcing later upshifts and earlier down-shifts, is intended to provide faster acceleration. But while this might be true for petrol engined models, the fact that the Vauxhall ECOTEC-4 engine produces its peak torque between 1,800 and 2,500rpm means that there is little, if any, benefit in holding on to gears. The third mode is "Winter", operated by a button next to shift lever marked with an ice symbol. This forces the transmission to start off in third gear to gain maximum traction on slippery surfaces. Other features of the transmission include extended up-shift points from cold to help with quick engine warm-up, and a standard oil cooler.

The upward gear shift process can be halted in any of the three lower gears by manually selecting positions 1, 2 or 3, which is useful for providing extra engine braking on hill descents. Third and fourth gears have a torque converter lock-up capability, which improves fuel economy by preventing slippage. Transmission "creep" at idle speed used to be a problem on automatics, but the GM box eliminates this by disengaging drive when the van is stationary and the brake pedal is firmly applied. This also allows a limited amount of drive at tickover to permit fine manoeuvring.

The automatic's purchase price premium of 1810, or 7%, is a known factor, but we were keen to discover what other, less obvious costs are involved, as well as disproving (or confirming) all those preconceptions about the efficiency of automatics. In theory, the very nature of the non-locking engine-to-gearbox connection provided by a torque converter should mean increased fuel consumption. But against that should be weighed the benefits of more constant throttle openings and general smoothness.

With the test van having covered enough distance to be decently loosened up, CM borrowed a identically powered manual Astravan and headed off to the proving ground to compare the pair back-to-back under identical conditions.

Productivity

The automatic transmission adds about 30kg to the van's kerbweight, but this is more than compensated for by a 60kg increase in GVW and front axle capacity (at least according to the plate on our example—the brochure quotes a 30kg increase). Despite this extra capacity on the front, the Astravan's Achilles heel remains its rear axle capacity The otherwise respectable 540kg net payload needs to be carefully loaded well forward to avoid a rear axle overload. All Astravans come with a steel half-height bulkhead, while the LS trim package includes a mesh upper section which is optional on the lower Envoy spec.

Our first big surprise came in the acceleration tests when the automatic took 12.3 seconds to cover the dash from 0-50mph; 0.7 seconds (or 5.7%) more than the manual. No surprise there, until you recall that our self-shifter was actually carrying a 5.9% greater payload. During mid-range testing the auto matched the manual from 30-50mph but lost 1.7 seconds from 4060mph. The torque converter slippage seems to be a positive help in overcoming the turbo lag which briefly delays the manual. In real life there's little to choose between the two versions; both are perfectly capable of performing at the level of a modern medium-sized 0 family saloon car, Roadworks at the bottom of our M20 test hsil precluded an accurate time being measured— suffice to say that at the end of the 40mph limit the Astravan swiftly accelerated to 70mph and stayed there for the rest of the climb.

The fuel consumption provides the other shock. Again remembering that extra payload, the automatic's thirst fully laden around CM'S Kent test route was 421mpg, which is 3.4% worse than the manual's. Unladen, the difference was 2.2mpg (or 4.4%). These figures are so close as to be subject to the vagaries of testing conditions; the truth is that the difference in fuel consumption is minimal—another myth dispelled.

On the read

A useful tip for any Vauxhall salesman is to warm up the 2.0-litre 16-valve engine before a test drive as the first minute or so involves a fair bit of direct-injection clatter, but this soon vanishes.

Starting off in economy mode actually gives fractionally better performance than in Sport, which with the diesel engine is more use around town. It also provides a quick and easy way to change down to improve engine braking, The change quality is very good, changes often only being perceptible by watching the rev-counter, as is the third and fourth gear lock-up.

In its element around town, the automatic is probably quicker off the mark than a manual, and is certainly safer. Obstacles like T-junctions and mini-roundabouts can be negotiated briskly, but with both hands on the wheel and with full concentration on other traffic. The torque converter softens the power delivery from a standstill, vastly reducing the wheelspin which is all too easily provoked by unleashing the Astravan's 185Nm of torque through a manual clutch. Hillstarts also benefit from this feature; although both vans were able to restart on a 40% (1-in-2.5) slope, the auto did so with much less wheelspin.

Ride and handling are more sports car than limousine, but ride comfort is rarely compromised by poor surfaces. The sharp steering of the Lotus-tuned chassis is a world away from the lifeless tiller of the old model, while the big discs haul down the van's speed in an impressive way And if you happen to leave your braking a little later than is wise, the electronic brake distribution prevents any dramas.

Summary

So do we recommend the automatic option? Critics (invariably uninformed) say it's for lazy or senile drivers, or those who've forgotten fun. But there's a difference between laziness and allowing technology to do a job if it can do it just as well. Common sense will tell you that the fewer tasks the human brain has to do, the less stressed it will become doing the remaining ones. In driving terms, having the gears look after themselves provides more time to concentrate on such details as steering and accelerating the van while avoiding other traffic.

The automatic van's benefits in city traffic are obvious and welcome but they are just as welcome driving briskly in the countryside, while in constant-speed traf

fie such as on motorways, the lock-up facility means there's simply no difference.

If the benefits for the driver are fairly self-evident, the bean counters might take more convincing over the effect on the bottom kne. There is a fuel economy penalty but it's considerably less than we expected, to the point where an automatic driven smoothly which its character encourages, is quite likely to better an indifferently driven manual.

Although there is no trading history to refer to yet,

the experts at Glass's Guide estimate that around 80% of the extra £810 cost of the automatic is likely to be retained after the first year, provided that no oversupply arises. Over the whole Astravan range the auto accounts for 2% of sales, but in the case of the LStrimmed 2.0 DI range-topper, the figure is over 17%.

We're certain that our initial impressions wore correct, but if you're not convinced, try one. You might just find that fun doesn't have to be hard work.

• by Colin Barnett