An Operator's Ideal Coach Chassis

Page 46

Page 47

Page 48

Page 49

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

Lightweight Coach Chassis for Day Excursions and Tours, Built by an Operator to Reduce Fuel and Tyre Costs : Proprietary Components Include Meadows Four-cylindered Engine and Overdrive-top Gearbox

By Laurence J. Cotton, M.I.R.T.E.

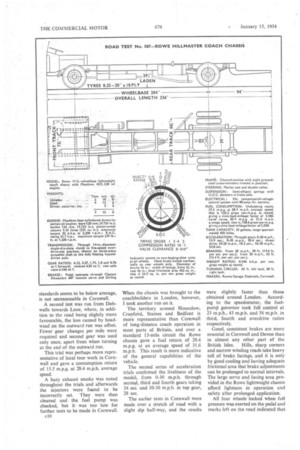

HIGH fuel and tyre billshave been responsible for a Cornish operator building a lightweight oil-engined coach chassis which is estimated to reduce costs yet provide good performance in the hillier parts .M the West Country. In many respects the chassis, built by Rowe's Garage, Dobwalls, resembles the Tilling-Stevens Express coach, being similar in specification and powered by the Meadows four-cylindered oil engine.

It has taken about two years to develop the Rowe prototype model, which weighs 2 tons 18 cwt. complete with spare wheel and full fuel tank. A Whitson 38-seat body to be fitted will add about 21 tons to the chassis weight, and allowing 21 tons for passenger load, the gross weight will be about 7 tons 13 cwt. As the coach is planned for day excursions and tours the only baggage carried would be small hand luggage, which would make no material difference to the total weight.

The engine, set to give 85 b.h.p. at 2,200 r.p.m. and 239 lb.-ft. torque, is mounted vertically at the front and has the Meadows gearbox attached as c8 a unit. This is mounted on Metalastik bonded supports in compression and shear at the front and by bobbintype units, outrigged from the clutch housing, at the rear.

A Borg. and Beck 14-in.-diameter clutch, with unsprung centre plate and roller-thrust bearing, is used. The Meadows five-speed gearbox has constant mesh on four ratios and, apart from a slight whine in overdrive, is quiet and easy to manipulate. The selector cover is arranged for direct linkage with the lever. _ A 17-ft. wheelbase .is ulfusual for a coach ,chassis which is designed for country operation, where manceuvrability is essential, or for a body of under maximum legal length, but such is the case of the Rowe, which has a maximum turning circle of 65 ft. For this length of wheelbase, and an engine mounted, at the front, a three-piece propeller shaft is required, in which two of the sections use Hardy Spicer mechanical joints and the central shaft has Layrub couplings. The intermediate centre bearings are retained in Laycock 120 mm. housings, which effectively isolate vibration and prevent transmission wind-up.

A Moss hypoid axle of 6.166 to 1 ratio is fitted, which, with the '8.2520-in. tyres, provides a maximum speed of 56 m.p.h. in overdrive and 43 m.p.h. in fourth gear. The superlow gear enables the coach to start

from rest, with full load, on a 1-in-4 gradient.

The long and steep gradients of Cornwall and Devon require exceptional braking; which is ensured by employing a Clayton Dewandre 6.87-in, servo and Girling hydraulically operated two-leading-shoe units in drums of 16-in. diameter. With the existing 2i-in.-wide shoes at the front and 41-in at the rear, the brake frictional area of 54 sq. in. per ton when fully loaded is adequate, but subsequent chassis will be provided with 3-in.-wide shoes at the front.

The nature of the work has enabled a light frame to be employed, the maximum section being 9 in. deep and 4in. thick, with a 3-in flange, and welded flitch plates in the region of the axles. A bolt-on dropped extension is provided at the rear. The rear overhang is 7 ft. and the overall length of the chassis is 27 ft. 9 in.

The long wheelbase promotes comfort, which is further improved by resilient springs 3,ft. 6 in. long at the front and 4 ft. 6 in, long at the rear. The latest U.D.C. telescopic dampers at the front axle obviate any tendency towards pitching, and the chassis does not roll noticeably on corners.

The spare wheel is mounted amidships. The 33-gallon fuel tank of rectangular section is to be replaced by one of the conventional cylindrical pattern. With standard 8.25-20-in tyres of 10-ply rating the frame height is 2 ft. 5i in. at the centre with the springs deflected under full load.

A central-entrance body is to be fitted, having a single seat at the front adjacent to the engine. The length of the front overhang and space alongside the bonnet and front wheel-arch might restrict gangway room if the entrance were placed ahead of the axle.

[tried the Rowe coach in its native county, having no difficulty in locating a suitable test hill within a few miles of Dobwalls, but flat stretches for acceleration runs are not easily found in Cornwall. The steering was put to test when driving through Liskeard, ivhich, like most towns west of Plymouth, has, narrow streets and sharp corners. Although an average proportion of the load was carried by the front axle, the steering was reasonably light and considerably less than that of the conventional heavier coach equipped with largersection tyres and similar steering gear. • Where conditions were suitable the vehicle sped along comfortably at 45 m.p.h., and frequent use of the brakes when cornering failed to pro duce evidence of fade. Heskyn Hill, near Salta.sh, was reached all too quickly, and after driving down to the valley, the chassis was turned in readiness for the ascent. Third gear was engaged before reaching the section of about 1 in 8 average gradient, which soon required a change to a lower ratio and finally to bottom gear when climbing the 1-in-5 gradient.

A stop-start test was staged at this point, and although the brake drums were hot there was ample movement left on the hand-brake lever when holding the chassis stationary on the gradient.

The test being successful, 1 then drove to Bodmin in preparation for a consumption trial across the moor towards Launceston. The moor stands high above the surrounding country, and, over the undulating A30 road, rises from 400 ft. above sealevel at Bodmin to 1,100 ft. mid-way to Launceston. Seemingly grach.g.: gradients are in fact fairly steep tali.' require frequent gear changing in a commercial vehicle.

The Rowe was subjected to a severe trial of economy, because on the outward and return runs long spells were covered in indirect gears, and second gear was required for two gradients. A stiff cross-wind added to the rigours of the trial, which was run at fair pace to afford an average of 28.8 m.p.h., for the two runs, including turning at Jamaica Inn. The fuelconsumption rate worked out at 133 m.p.g., which, although by normal standards seems to be below average, is not unreasonable in Cornwall.

A second test was run from Dobwalls towards Looe, where, in addition to the road being slightly more favourable, the loss caused by headwind on the outward run was offset. Fewer gear changes per mile were required and second gear was used only once, apart from when turning at the end of the outward run.

This trial was perhaps more representative of local tour work in Cornwall and gave a consumption return of 15.5 m.p.g. at 28.4 m.p.h. average speed.

A hazy exhaust smoke was noted throughout the trials and afterwards the injectors were found to be incorrectly set. They were then cleaned and the, fuel pump was checked, but it was too late for further tests to be made in Cornwall.

c10 When the chassis was brought to the coachbuilders in London, however, I took another run on it.

The , territory around Hounslow, Cranfotd, Staines and Bedfont is more representative than Cornwall of long-distance coach operation in most parts of Britain, and over a standard 13-mile circuit the Rowe chassis gave a fuel return of 20.4 m.p.g. at an average speed of 31.6 m.p.h. This result is more indicative of the general capabilities of the vehicle.

The second series of acceleration trials confirmed the liveliness of the model, from 0-30 m.p.h. through second, third and fourth gears taking 34 sec. and 10-30 m.p.h. in top gear, 28 sec.

The earlier tests in Cornwall were made over a stretch of road with a slight dip half-way, and the results were slightly faster than those obtained around London. According to the speedometer, the fuel-. pump governor took full control at 23 m.p.h., 43 m.p.h. and 56 m.p.h. in third, fourth and overdrive ratios respectively.

Good, consistent brakes are more essential in Cornwall and Devon than in almost any other part of the British Isles. Hills, sharp corners and narrow winding roads take heavy toll of brake facings, and it is only by good cooling and having adequate frictional area that brake adjustments can be prolonged to normal intervals. The large servo and facing area provided in the Rowe lightweight chassis afford lightness in operation and safety after prolonged application.

All four wheels locked when full pressure was exerted on the pedal and marks left on the road indicated that the wheels were stationary for over 40 ft. in stopping distances of 60-63 ft. from 30 m.p.h. The hand brake, too, was effective being well capable of locking the wheels on a damp road.

Under the best conditions, Tapley readings of 38-39 per cent. were recorded for the hand brake. With a result of this standard there should be no difficulty in passing any Ministry of Transport test of braking efficiency.

The chassis has all the ingredients necessary for trouble-free operation under exceptionally severe conditions, and its performance compares reasonably with that of heavier contem porary models. The few Tilling Stevens Express coaches that were built and operated have given remarkable service, and there is no reason why the Rowe lightweight coach should not be equally successful. It is intended to build more of these chassis and to offer some to other operators whose problems may be similar to Mr. Rowe's.