Hire and reward

Page 54

Page 55

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

Few tales sum up the early reputation of agency drivers as vividly as the one about the distribution manager in west London during the early 1980s—he used to keep his agency contact numbers on the side of a large box of Aspro so he could always be sure of reaching for the correct solution to the inevitable headache whenever he was short of a driver.

Like many other traffic managers of the time, he was on a loser. If the customer didn't scream blue murder about late deliveries, union reps would bang on the table complaining about his use of casual labour.

Today's reputable driver agencies have come a long way: so have the companies that use them, and the attitude of the unions.

No longer seen as a threat to union jobs, agency driver numbers have risen and their acceptance was apparently confirmed last month when the United Road Transport Union announced plans to set up its own driver agency early next year (CM25-31 Jan).

Existing agencies welcome a move which they see as an endorsement of their practices: "We've worked very closely with the trade union movement and actively encourage our drivers to join," says national account manag er for drivers at Manpower, Nick Peligno. "Like us, they (URTU) appear to be offering holiday pay benefits, wages at the market rate and strict adherence to Drivers' Hours Regulations. Anything which seeks to achieve those aims can only be good for the market" So far there have been no hostile reactions to a move which John Lloyd, lecturer in industrial relations at Cranfield School of Management, suggests could be a case of a union addressing the world as it is rather than as it would like it to be.

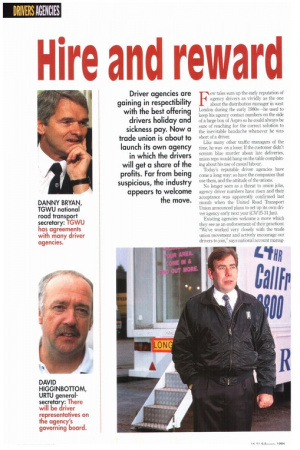

But is there not a conflict of interest for a union representing drivers which it also employs? URTU doesn't think so. Normal disciplinary and grievance procedures will apply and a driver will be represented by URTU or any other union he belongs to. "URTU will own the business but there will be driver representatives on the governing board," says a spokesman. The board will also include independent legal advisers, the union's accountant and its chairman will be David Higginbottom, the union's general-secretary.

However, by the time the agency begins operating in April 1997 a chief executive will have been appointed with experience of the agency world. Half the profits will be paid out to drivers and other employees; the remaining 50% will be ploughed back into the business. URI!: likens the project to a working men's club in which a committee is elected or appointed to run its affairs.

Neither is the URTU agency seen as a sellout by other unions. For many years branches of the Transport & General Workers Union have been supplying names of unemployed drivers free of charge to prospective employers. National road transport secretary Danny Bryan confirms that the TGWU has agreements with many driver agencies; he says the union has an open mind about LaTU's ideas -a view echoed by John Hannett, national officer at the Union of Shop, Distribution and Warehouse workers.

CRTU's plans to include profit sharing appear to fit comfortably with the Labour Party's view of a "stakeholder economy". Other planned benefits compare favourably with the packages offered by the major agencies hoping to attract the best.

"The agencies don't just take on any Joe Soap and the drivers have to be more versatile and much more professional," says Errol Smikel. "Taskforce puts you through rigorous tests. It makes it harder to get into the agency than into some major companies." These are not the words of an agency spokesman, but a former agency driver. He was trained and fully employed by BRS Taskforce—the agency which supplies NITC and many other large operators—for well over two years. Taskforce now has around 1,200 drivers.

Rory Skinner, manager for BRS Taskforce in Nottingham, says that this training includes ADR regulations and tanker driving, supported by on-the-job tuition and regular assessments.

With up to 2,500 goods drivers employed every week, the biggest agency is Manpower. Most of its drivers are employed full-time and, like Taskforce, Manpower runs a thorough screening process. After checks on an applicant's licence, medical history and references, there are written tests: "Many of the tests are diagnostic. From that we can provide further support and training on lorry loaders, lift trucks and conversion to drawbar driving through our fleet of training vehicles at our training centre in Egham," says Manpower's Nick Peligno.

The result is that forward thinking agencies can now command pools of fully employed temporary driving specialists who can deliver goods to your customer and smile at even the grumpiest loading bay supervisor.

"You could be delivering for a supermarket like Safeway, then go to work for companies like Do it All or Texas where you could be dealing with the general public. Next day you could go into a factory where you have to blow off a tanker when you are on your own. You had to be smart and your attitude had to be right all the time," says Smikel, who now works on the Ford contract at sister company Exel Logistics. It doesn't pay as well, but the regular hours suit him better.

It is the comparison of cost between regular and temporary hours that is making the use of agency drivers appear so cost effective for employers, particularly in the retail distribution industry.

Glasgow-based Topstaff Employment has 90 drivers on its register, but so far only two of them are full-time employees. Director David Stephens says much of his business comes from the retail sector and he explains that the retailers' principles of convenience shopping is now being applied to drivers and increasing the demand.

"They now see advantages which perhaps they did not see before," he says. They can click their fingers and get precisely the quality of staff they want, when they want them, without having to prime the personnel departments to recruit them."

On average, for every L6-10 an hour a permanent employee earns, an extra 25% of costs are generated by employment benefits, national insurance, uniforms and administration.

Non-productive time is extra. At 1:6-,E8 an hour for an agency driver, it makes economic sense to use them—and they don't clutter up the canteen in slack periods.

Adrian Hobbs is managing director at the Hinkley-based Round Pegg employment agency It has 140 full-time drivers on its books and also operates a screening and training programme. Hobbs reckons that for many clients agency drivers have become an integral part of the planning process.

"They are used strategically," he says, "to minimise the fixed costs and to improve the flexibility and utilisation of their businesses through the peaks and troughs of demand."

One major retailer says that it only employs enough permanent drivers to meet its minimum requirements, with agency drivers used to cope with changes in volume.

If this is a growing trend, it could be good news, and good timing, for URTU, which already claims support from some supermarket chains.

Some might consider it strange that a union could even contemplate running a business once seen as a threat to the professional driver. However, in recent years the more reputable agencies have been responsible for enhancing the image of goods drivers through continually updating and assessing their skills—and that must seem stranger still.

Li by Steve McQueen