The oil companies know as much as anyone about how

Page 31

Page 32

Page 33

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

to cope with fire hazards. David Wilcox has been on a course organised by BP for its drivers AFIRE on any vehicle is distinctly unwelcome; on a 30,000-litre (6,000 gallons) petrol tanker it does not hear thinking about.

But BP has to think about it. For the company's distribution division this means regular refresher courses on tire fighting for the 600 road tanker drivers.

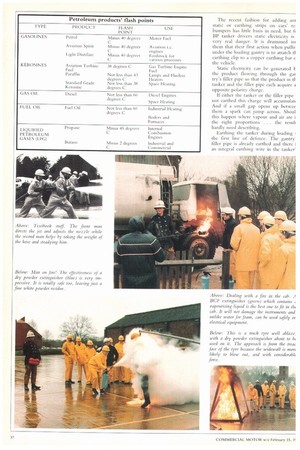

The drivers attend the two-day course in groups of 12 once every four years. Along with several other trade publications CM was recently invited to join a condensed, one-day version of the course "and find out what it is like to grab a bucking hose".

Refresher courses arc held regionally at tire brigade training grounds; we went down to one at Maresfield in Sussex which BP had hired for the day from East Sussex Fire Brigade. The course was run jointly by BP's own training officers and instructors from the Petroleum Training Federation, an industry-financed body which offers professional training to the oil companies. The fire-fighting course for drivers is designed to make training as practical and participative as possible. This means some instruction in the classroom followed by real flames.

Like the other oil companies BP carries a variety of products, some of which are officially "dangerous" and appear on the approved list of the Dangerous Substances (Conveyance by Road in Road Tankers and Tank Containers) Regulations 1981. In the case of petroleum products it is largely the product's flash point that determines this classification. The flash point is the lowest tempertature at which a liquid will generate sufficient vapour to produce a flash when exposed to a source of ignition. Products with a flash point below 55°C are classified as "dangerous".

Petrol (or motor spirit in oil industry terminology) easily falls into this category; its flash point is minus 40°C, meaning that in the UK climate it will always give off sufficient vapour to ig

nite. Kerosienes such as paraffin have a flash point of 38-43°C and so are less dangerous at ambient temperatures, but they still warrant the dangerous label.

Diesel fuel has a flash point of 66°C and so it is not in the dangerous category.

Tanker drivers have to know the properties of the products they carry so that they can handle a spillage correctly and avoid having to put their firefighting expertise to the test. For example, in the event of a small spillage of petrol the driver needs to know where to find the lethal vapours without striking a match.

Petrol vapour is two to four times heavier than air and so readily runs downhill to collect in pits, basements and ditches where it will stay unless there is proper ventilation. The petrol itself has a specific gravity that is less than one, so it will float and be carried on running water into drains or rivers.

The recent fashion for adding ant static or earthing strips on cars' re. bumpers has little basis in need, but fi BP tanker drivers static electricity is very real danger. It is drummed im them that their first action when pullir under the loading gantry is to attatch ti earthing clip to a copper earthing bar c the vehicle.

Static electricity can be generated tl the product flowing through the gal try's filler pipe so that the product in tF tanker and the filler pipe each acquire a opposite polarity charge.

If either the tanker or the filler pipe not earthed this charge will accumulati Arid if a small gap opens up betwee them a spark can jump across. Shout this happen where vapour and air are i the right proportions . . . the result hardly need describing.

Earthing the tanker during loading i the first line of defence. The gantry' filler pipe is already earthed and there i an integral earthing wire in the tanker' elivery hose to cope with static generaon during discharge. Pump rates are lso set at a level that minimises the uild up of static.