Treatment of Goods Traffic at Stations.

Page 24

Page 25

Page 26

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

How the Problem is Being Solved. By Fred. W. West.''

;Concluded from page 442.) The method adopted of loading goods in wagons I regard as one of the most important responsibilities that any officer in charge of a station has to bear ; it is the most difficult to control and regulate. An error of judgment in this department might cause an article to fad off a wagon during its transit with more or less serious results, and yet no instructions can be laid down in detail to show a loader how the miscellaneous and ill-assorted articles he has to -deal with can be made so to fit together as to prevent such .a contingency. Needless to say, it is the universal practice to allow none but thoroughly experienced men to act as loaders, and for their work to be carefully supervised by still more experienced foremen, but I do not myself believe that perfection in this direction will be reached until open wagons are replaced by covered vans for the conveyance of sundry goods and other traffic, which is liable to fall on the line and cause obstruction. This class of vehicle, .moreover, has the additional advantage of saving labour in .sheeting and damages to goods by wet during transit through faulty covering. Apart from the necessity of loadingthe goods so that there will be no risk of any article falling on to the line, however, they must be packed together in such a manner that they wiil not be damaged by the oscillation of the wagon while running or being shunted, and so that they will not injure one another. How this is done is the art of the practical loader, who alone kno‘k s the secret, and it is only by much experience in the actual handling of the goods that it can be properly acquired. It is, of course, an easy thing to understand that a jar of spirits should not be placed between ra couple of barrels of beer, or between other heavy articles that may be likely to oscillate during shunting; also, that

• the leg of a dining-room table should not he allowed to rest on the face of a pier glass; but there is no golden rule to show how a quantity of mis.cellaneous goods should be loaded in an open truck s as 13,_.A to economise space and

.yet to secure both the safety the line and the packages. The Crewe tranship shed affords exceptional scope for

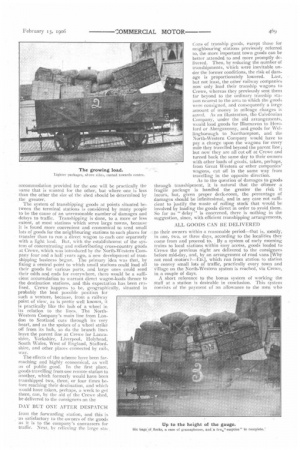

education in this respect. There, in busy seasons, the traffic averages 1,000 tons a day. It is made up of 7,000 .consignments, or 25,000 packages, and embraces almost .every variety of article known in British commerce, from a hag of animal offal to a box of hot-house flowers! For the purpose of illustration, I recently analysed a typical load of goods for Swansea, which was made up in a high-sided " four plank " wagon, and photographs are reproduced of the truck as it appeared duringthree different stages of the loading. The goods consisted of 46 consignments, made up of 226 prckages, divided into 25 different classes of merchandise, and they weighed seven tons, which, vou will observe, gives an average of 3qr. 221b., or a little short of a hundredweight a package : the contents were practically all things that people eat, use, or year.

The first photograph shows the box and truss classes evenly packed in the well of the wagon, with straw between the articles which arc liable to be damaged by friction. A space is left in the middle, opposite the drop-down door, for the loader to work until the second tier of goods is commenced, and then this is used for the reception of articles such as castings, bags of nails, and other things which do not lend themselves to solid loading at the ends of the truck.

The second photograph shows the load when it has grown above the sides of the truck, with a crate of earthenware at one end and a case of boots at the other, both canted down from the end of the truck towards the centre so as to throw the weight in that direction.

The third photograph shows the load completed up to the height of the gauge, with six bags of flocks, a case of gramophones, and some empty packages placed on the top.

It is, perhaps, unnecessary

for me to add that it is not every wagon that secures .a 7ton load, because Crewe loads directly to 330 different stations a day, and there are many for which there is not more than a .ton or so of goods a day; but my object is to shcw that a

GREAT WEIGHT OF ODDS AND ENDS

of merchandise may be loaded, even in an open wagon, with perfect safely. if the loader knows how to do it. With regard to the " inwards " or " receiving " department, I need not say much on the point of the handling of goads, because we simply reverse the process of " forwarding "; that is to say, we take the goods from wagon to cart instead of vice versa. The necessity for adequate accommodation, however, is equally great, and I measure the mini_ mum requirements for thoroughly economical working to be (1) wagon-space in the shed for as many wagons as are received daily, and (2) a loading platform, 23 it. wide, long enough to serve the whole of the stations' working teams when hacked up at one time for loading. The reason for the first provision is that it frequently happens that the latest wagons to arrive contain the most urgent goods for delivery, and should be, therefore, readily " get-at-able " instead of having to wait their turn to he worked into the shed behind less important traffic. Further, the majority of the wagons, after being emptied, would be in position for " outwards " loading, whilst many of the others could he similarly, placed by means of traversers, thus greatly reducing the shunting by engine and capstan, which is inevitable under other conditions. The second provision is required to permit the goods—so far as is practicable —to be hand-trucked on to the waiting lorries, and to avoid double handling, with consequential expense and risk of damages. In short, where the " inwards " traffic is about equal to the " outwards," as it is in many cases, the

accommodation provided for the one will be practically the same that is wanted for the other, but where one is less than the other the size of the shed should be determined by Ate greater.

The system of transhipping goods at points situated between the terminal stations is considered by many people to be the cause of an unreasonable number of damages and delays to traffic. Transhipping is done, to a more or less extent, at most stations which serve large towns, because it is found more convenient and economical to send small lots of goods for the neighbouring stations to such places for transfer than to run a direct wagon to each one separately with a light load. But, with the establishment of the system of concentrating and redistributing cross-country goods at Crewe, which was introduced by the North-Western Company four and a half years ago, a new development of transhipping business began. The primary idea was that, by fixing a central point to which small stations could load all their goods for various parts, and large ones could send their odds and ends for everywhere, there would be a sufficient accumulation to warrant direct wagon-loads thence to the destination stations, and this expectation has been realised. Crewe happens to be, geographically, situated in probably the best possible position for such a venture, because, from a railway point of view, as is pretty well known, it is practically like the hub of a wheel in its relation to the lines. The NorthWestern Company's main line from London to Scotland cuts through its very heart, and as the spokes of a wheel strike off from its hub, so do the branch lines leave the parent line at Crewe for Lancashire, Yorkshire, Liverpool, Holyhead, South Wales, West of England, Staffordshire, and other places connected by rail-,

XVity.

The effects of the scheme have been farreaching and highly economical, as well as of public good. In the first place, goods travelling from one remote station to another, which formerly would have been transhipped two, three, or four times before reaching their destination, and which would have taken, perhaps, a week to get there, can, by the aid a the Crewe shed, he delivered to the consignees on the

DAY BUT ONE AFTER DESPATCH from the forwarding station, and this is as satisfactory to the owners of the goods as it is to the company's canvassers for traffic. Next, by relieving the large sta

Eons of tranship goods, except those for neighbouring stations previously referred to, the more important town goods can be better attended to and more promptly delivered. Then, by reducing the number of transhipments, which were inevitable under the former conditions, the risk of damage is proportionately lowered. Last, but not least, the other railway companies now only load their tranship wagons to Crewe, whereas theypreviously sent them far beyond to the ordinary tranship station nearest to the area to which the goods were consigned, and consequently a large amount of money in mileage charges is saved. As an illustration, the Caledonian Company, under the old arrangements, would load goods for Blaenavon to Hereford or Abergavenny, and goods for 1Vellingborough to Northampton, and the North-Western Company would have to pay a charge upon the wagons for every mile they travelled beyond the parent line; but now they are all cut off at Crewe and turned back the same day to their owners with other loads of goods, taken, perhaps, from Great Western or other companies' wagons, cut off in the same way from travelling in the opposite direction. As to the question of damages to goods through transhipment, it is natural that the oftener a fragile package is handled the greater the risk it incurs, but, given proper deck-room, the percentage of damages should be infinitesimal, and in any case not sufficient to justify the waste of rolling stock that would be involved by loading the goods direct in order to avoid them. So far as "delay " is concerned, there is nothing in the suggestion, since, with efficient transhipping arrangements,

ALL GOODS CAN BE DELIVERED to their owners within a reasonable period—that is, mostly, in one, two, or three days, according to the localities they come from and proceed to. By a system of early morning trains to local stations within easy access, goods loaded to Crewe the previous night are delivered to the consignees before mid-day, and, by an arrangement of road vans [Why not road motors ?—ED.], which run front station to station to convey small lots of traffic, practically every town and Village on the North-Western system is reached, via Crewe, in a couple of days.

A short reference to the bonus system of working the staff at a station is desirable in conclusion. This system consists of the payment of an allowance to the men who

handle traffic, upon the Nyork they perform beyond a prescribed quantity, and it is in addition to their fixed wages. I need not enter into the details of the arrangement, because they vary according to the local circumstances of each station where the scheme is in operation. I will merely say that at Crewe, where it was introduced about 3l years ago, the men increase their wages by sums varying from a penny to iss. a week. Now, the object of the system is to give the men an inducement to get through their work more quickly than they would do under ordinary conditions, and it is rather commonly supposed that it leads to more reckless and less efficient working. This is a mistake wish to correct. The economy of the system really lies in the two facts that the men are persuaded to refrain from wasting time, and that they automatically OUST IDLERS FROM THEIR MIDST.

Without a bonus allowance the average man will dawdle over his work to some extent, no matter how close the supervision may be, and he will not, voluntarily, take away a hundredweight of goods upon his barrow if he can get off with half that quantity. Neither will he hurry back with his empty truck for another load : he will do everything as leisurely as possible. But, with an allowance, see hint move ! His load is determined by the capacity of his barrow, and, when he has got it, he requires no urging to take

it away smartly. Nor does the foreman need to watch and see that he returns promptly for the next lot. Working in a gang, as he does, his mates see that he does his share of the labour, for their mutual good, and if any man in the gang fails in this respect, the others soon get him sent to the " rightabout." On the other hand, an unskilled labourer, who can earn from 3os. to .4:2 a week, as he can in the Crewe shed, appreciates his job sufficiently to be amenable to the strictest discipline and supervision over his work, and this he gets. The inspectors and foremen, who are no longer under the necessity of devoting a large portion of their time to pushing the men along, apply themselves assiduously to seeing that the work is done well. The men altogether are much more contented and satisfied, which makes for good from every point of view, and when I mention that last year they had divided between them, in proportion to their merits, no less a sum than 4;2,738 by way of bonus allowances, averaging Lii a man, I think you will agree that they had good reason to be so.

Summarising the foregoing, I will put it that the chief desiderata for the proper treatment of goods traffic are : (i) Adequate accommodation for its manipulation; (2) a central transhipping shed for accelerating the transit of the sundry goods; and (3) a " profit-sharing " or " bonus " scheme for the staff, to secure their active interest and cooperation in the work.