single-deck bus

Page 48

Page 49

Page 50

Page 53

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

By R. D. Cater AMInstBE STANDARDIZATION of chassis by operators is a sensible and natural course to take, but it's seldom possible to persuade makers to incorporate the necessary changes in their products and allow the ultimate—a one-make fleet.

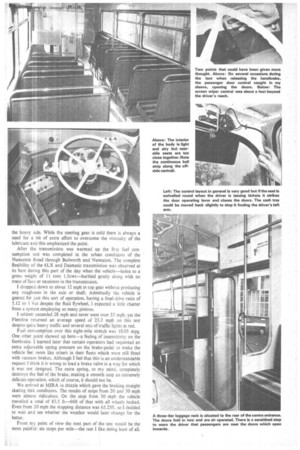

The Daimler Fleetline is, by now, a familiar double-decker, but this is the first road test of a single-deck version of this type with bodywork by East Lancashire Coach Builders Ltd., built for service with Bury Corporation Transport. Using the Fleetline chassis for single-deck operation gives this operator an extra slice of standardization, for the fleet already includes 21 double-deck Fleedines.

Most of the features of this six-year-old Fleetline design are retained in the vehicle tested, but the Gardner 6LX engine was derated from its normal output of 150 bhp to 125 bhp, and its torque output was 405 lb.ft. at 1,100 rpm instead of the usual 485 lb.ft.

Only one major change has been made to the Fleetline since it was first introduced at the Commercial Motor Show in 1960. The Daimler CDV6 diesel engine fitted then has been discontinued and the two alternative engines available now are the Gardner 6LW and 6LX models. More recent changes include lowering the front-axle 'dampers, so dispensing with the need to raise the floor-line in this vicinity.

The steering gear, too, has been changed from 33 to 1 to 40 to 1. The vehicle tested, however, was the first of its type and did not include these alterations. When I complained after the test that the steering was heavy, I was told that this had already been altered on later production models.

The test vehicle, with 15,100 miles on the speedometer, was taken out of service by Bury Corporation specially for this test. No special preparation other than the removal of the rear body panel—to allow the mounting of a fuel test tank—had been carried out.

Atrocious weather and the fact that the vehicle belonged to an operator prompted me to carry out the tests at MIRA. There is far less likelihood of running into trouble during brake tests or the six-stops-per-mile fuel consumption checks here than on the open road. But at COMMERCIAL MOTOR we suspect that the results obtained on the MIRA circuit do not reflect accurately operating conditions.

The handling of numerous heavy vehicles develops an instinct over the years as to whether a vehicle is right or not. I have long ceased to be surprised when test figures bear out first impressions. The Fleetline felt good, and considering the type of work that it is designed for, the results confirm the wisdom of Bury's specification.

Completely at home

The test started at the Daimler works at Radford Road, Coventry, and apart from a rather excessive amount of creep when first or second gears were engaged I was straightaway completely at home with the Fleetline. Adequate adjustment of the driver's seat allows the maximum in driving position comfort and the utter simplicity with which gear changes are accomplished takes most of the tedium out of bus driving.

Negotiating the narrow back-streets, which lead out from Coventry on to the Nuneaton Road presented no problems, but it was in this section that I first suspected that the steering was on

the heavy side. While the steering gear is cold there is always a need for a bit of extra effort to overcome the viscosity of the lubricant and this emphasized the point.

After the transmission was warmed up the first fuel consumption test was completed in the urban conditions of the Nuneaton Road through Bedworth and Nuneaton. The complete flexibility of the 6LX and Daimatic transmission was observed at its best during this part of the day when the vehicle—laden to a gross weight of 11 tons 1.5cwt—burbled gently along with no trace of fuss or nastiness in the transmission.

I dropped down to about 12 mph in top gear without producing any roughness in the axle or shaft. Admittedly the vehicle is geared for just this sort of operation, having a final-drive ratio of 5.12 to 1 hut despite the fluid flywheel, I expected a little chatter from a system employing so many pinions.

I seldom exceeded 28 mph and never went over 33 mph. yet the Fleetline returned an average speed of 23.2 mph on this test despite quite heavy traffic and several sets of traffic lights at red.

Fuel consumption over this eight-mile stretch was 10.05 mpg.

One other point showed up here a feeling of insensitivity on the footbrake. I learned later that certain operators had requested an extra adjustable spring pressure on the brake-pedal to make the vehicle feel more like othefs in their fleets which were still fitted with vacuum brakes. Although I feel that this is an understandable request I think it is wrong to load a brake valve in a way for which it was not designed. The extra spring, to my mind, completely destroys the feel of the brake, making a smooth stop an extremely delicate operation, which of course, it should not be.

We arrived at MIRA in drizzle which gave the braking straight skating rink conditions. The results of stops from 20 and 30 mph were almost ridiculous. On the stop from 30 mph the vehicle travelled a total of 83.5 ft-66ft of that with all wheels locked. Even from 20 mph the stopping distance was 65.25ft, so I decided to wait and see whether the weather would later change for the better.

From my point of view the next part of the test would he the most painful: six stops per mile—the test I like doing least of all. Here for the first time since picking the vehicle up at Coventry the derating of the engine was noticeable because, while doing this test I found it almost impossible to raise the road speed to 30 mph between stops, the usual maximum obtainable being around 25 mph. Consequently the rather low average speed of 11.1 mph was returned while the fuel consumption was disappointing at 6.8.mpg. While I appreciate the motives behind derating an engine for this sort of application, the resulting lack of power must often be as detrimental to fuel consumption.

With only 1,700 rpm and the 5.12 to I final drive ratio, the vehicle produced a maximum road speed of exactly 38 mph. Because of this, fuel tests for 40 mph non-stop and for maximum speed, must be the same. Fuel consumption results can be seen in the accompanying panel, and it is interesting how much they improved as the'load was taken off. And the 30 mph non-stop empty figure was more than doubled at 111 per cent better than that obtained fully laden at six stops per mile.

During the six stops test I noticed that the oil warning light came on each time the vehicle came to rest. I inquired about this at the works. The 6LX is supposed to idle at about 25 p.s.i., oil pressure and next day a pressure gauge was fitted to allay my suspicions.

In true Gardner style the engine produced exactly 25 p.s.i. at idling speed with the lamp just out. I concluded that on the previous day the engine-oil viscosity had dropped .sufficiently to allow the 25 psi. switch to operate, switching on the light. Although this satisfied me technically, the fact is that if a warning light continually lights up it will soon become dis-, regarded by the driver and could conceivably result in a wrecked engine.

It continued to rain for the rest of the day but we were successful--with the help of the MIRA controller Mr. W. H.

Dolby—in finding a suitable stretch of road to do brake tests. This had a similar adhesion character when wet as most dry roads. Slight pulling to the nearside was evident on all the stops made but at no time did this produce any cause for anxiety. The results were better than expected with the service brake producing average distances of 26.7ft from 20 mph and 53.Ift from 30 mph. Tapley meter readings of 66.0 per cent were recorded from both speeds. The hand brake produced an extremely acceptable figure of 27 per cent. A fade test was carried out after completing the six stops per mile when 29 stops at 0.3g had been made. A full-pressure stop produced a Tapley meter reading of 45 per cent from 20 mph, Too much The 1 in 6 test hill at MIRA proved too much for the Fleetline and it was only by racing the engine and banging the first gear in that I was able to persuade it to reach the summit. Once over the top and on the I in 5 at the other side reverse gear—which is a lower ratio 5.53 to 1 as opposed to 4.51 to 1—would have comfortably heaved the machine back over the top. Unfortunately the band on this gear had probably never been adjusted from new and it chose this moment to slip. This is not surprising because in bus operation reverse gear is seldom stressed beyond the amount needed to back the vehicle along level ground. After adjustment reverse gear functioned perfectly.

During night-driving I was troubled by considerable amount of reflection in the screen, and this was aggravated by a quite large unwiped area of screen when raining. Then, when the interior lights were switched on an ear-splitting squealing emanated from the control gear. All on board found this impossible to live withso I drove back to Radford works without interior lighting!

As this type of vehicle is seldom running at more than 25 per cent loaded it seems fair to expect an overall fuel consumption of 9 to 10 mpg. And derating should enable exceptionally high mileages to be covered without major attention to the power unit-probably the whole projected life of the vehicle. Thus, as an economic proposition the Fleetline must rate as one of the more attractive single-deckers available today.