3. Producing monthly servicing and repair costs for the Flow-line system

Page 52

Page 53

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

Provision is made in the 1967 Road Safety Act for records to be kept of inspections and maintenance and for the retention of these records for periods up to 15 months. The regulations may apply to all goods vehicles or to such classes as are prescribed; provision is made for the inspection of these records and of those which have to be kept to show the action taken to remedy any defects discovered on an inspection. It will be seen, therefore, that irrespective of where or by whom the vehicles are maintained, there can be an obligation, on every operator to maintain such records, including those of vehicles hired without drivers.

As a personal opinion I suggest that a Ministry examiner is unlikely to be impressed by evidence of a large expenditure on a particular vehicle in any one month when it is apparent that the abnormal cost—excluding major units such as engines and gearboxes—ought to have been incurred previously over a period.

Just as we have put the driver's daily log sheet to better use, so the opportunity occurs to employ the statutory inspection and maintenance records in a manner in which they can be profitably used to record individual vehicle maintenance costs. I have seen attempts by operators of small and large fleets to record these costs but with a few exceptions what I have seen has been

mainly a guesstimate of labour and material costs, which may include a notional element of overhead costs.

Stock control and profit Rarefy have I seen any control exercised over materials drawn from stores, which must make it very difficult for an accountant to maintain an accurate stock account. The book-keeping procedure usually employed is to debit all parts purchased and outside repair costs to the transport repair account and then at the year end, or even later on when the auditors are in, to take a rough stock check, the estimated value of which is credited to the repairs account. This is another area in which profit leaks are rife, as although it may be said that what was purchased must have been used on the vehicles if it isn't in stock, the absence of stock control, which can be quite simple, does not reveal obsolescence or stock losses. The result is that spare parts for vehicles long since replaced by other makes tend to accumulate.

The stock figure as certified by the chief executive influences the stated profit and, since stock is part of the assets employed, the figure affects the yield on the capital invested. Consequently, the higher the closing stock figure the greater the taxable profit, and although the small family busi

ness may not be aware of this the larger companies with a responsibility to shareholders need to ensure that the declared stock value will withstand investigation.

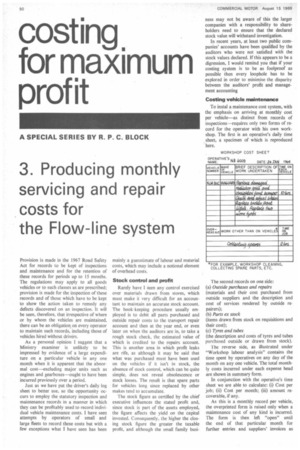

In recent years, at least two public companies' accounts have been qualified by the auditors who were not satisfied with the stock values declared. If this appears to be a digression, I would remind you that if your costing system is to be as foolproof as possible then every loophole has to be explored in order to minimise the disparity between the auditors' profit and management accounting Costing vehicle maintenance To instal a maintenance cost system, with the emphasis on arriving at monthly cost per vehicle—as distinct from records of inspections—requires only two forms of record for the operator with his own workshop. The first is an operative's daily time sheet, a specimen of which is reproduced here.

The second records on one side: (a) Outside purchases and repairs (materials and their cost purchased from outside suppliers and the description and cost of services rendered by outside repairers); (b) Parts ex stock (items drawn from stock on requisitions and their cost); (c) Tyres and tubes (the description and costs of tyres and tubes purchased outside or drawn from stock).

The reverse side, as illustrated under "Workshop labour analysis" contains the time spent by operatives on any day of the month on any one vehicle. The total monthly costs incurred under each expense head are shown in summary form.

In conjunction with the operative's time sheet we are able to calculate: (1) Cost per job; (ii) Cost per month; (iii) amount recoverable, if any.

As this is a monthly record per vehicle, the overprinted form is raised only when a maintenance cost of any kind is incurred. The form is then left "open" until the end of that particular month for further entries and suppliers' invoices as received. The labour and material costs, including tyres, if any, but excluding engine oil, are then totalled and transferred to the "Tyre and repair cost summary" including any recoverable expenses. The completed form is then ready for processing by the costing section, the function of which will be described separately later on.

As you can see, the total expenditure during January, less costs recovered, less the cost of the engine oil, which will subsequently be recorded elsewhere, provides us with net maintenance costs for the month of £30 9s 3d plus £54 for tyres. The recoverable items (in this case an accident claim) are evidenced by some of the materials fitted by the operative and confirmed by the parts purchased on Invoice No. 9042 as supplied by "Allparts Limited" together with a proportion of the cost of the first two stock items drawn on Requisition Nos_ 606 and 607.

The difference between the amount recovered and the actual cost of the accident repairs lies in the fact that this operator is carrying an excess on his insurance policy. Note also that the £4 to be recovered is confirmed by Sales Invoice 1No. A.7632, an example of reconciling costing with financial accounting.

As maintenance and tyre costs may account for some 15 per cent of total costs, of which 12 per cent is maintenance, which must continue to increase, it is not a cost to be treated lightly and, consequently, a closer study of the example illustrated here with some further explanation of the detail should be time well spent. Our immediate objective, remember, is to ascertain individual vehicle maintenance costs per month. The operator without a workshop need only complete that side of the overprinted form headed "Vehicle repair costs (parts and tyres)" as all the information he requires will be taken from outside suppliers' invoices; consequently, his vehicle repair costing will have been completed for him through the medium of his repairers' invoices. The Flow-Line processing of this information will be described subsequently.

Workshop overheads

To calculate labour costs per vehicle we know that the operator with his own workshop required a daily time sheet from each operative. Looking at our example again, we see that on January 24 Fitter N. B. Good booked 10 hours on vehicle number KLM 311C. In addition, he booked two hours collecting spares, and had this time been solely for the work in hand he would have booked 12 hours against the vehicle. As it was, he collected stores accessories for use on other vehicles and, consequently, these two hours will be treated as on "Overhead A IC". This is indicated by its omission from the "Workshop labour analysis" for the month, so you will want to know what happens to the two hours booked on "Overhead A /C", to which I will refer in a later instalment. For the time being it is sufficient to say that at the beginning of every month you must raise a monthly "Vehicle repair costs" record, substituting "Fleet" or "Vehicle No." by "Overhead A/C".

You can see that the "Labour analysis" provides for a number of operatives to work on the same vehicle during the course of a month; thus a vehicle undergoing an overhaul in a large workshop will be debited with times recorded by other tradesmen, e.g. electricians and bodywork repairers, etc. If after an overhaul the vehicle is road tested by a workshop operative, he will book his time to it, but if fleet inspectors are employed for this specific purpose. the cost of their time will be regarded as an "Overhead A/C". In the "Tyre and repair costs summary" 24 hours are charged to KLM 311C at the operative's hourly rate of 9s and the amount to be recovered at lOs per hour is intended to cover "overhead costs"—but does it? How about those expenses associated with the operation of a workshop such as rent, rates, lighting and heating, foremen's wages and expendable stores, and so on? These costs have to be calculated and then allocated in an equitable form to the vehicles using the workshop facilities.

How we quantify these "hidden costs" is a subject in itself, but as they are similar in principle to the calculation and spread of establishment costs I shall deal, with these two insidious profit leaks when we need to use this information. In the meantime, we have reached a stage in our preparatory work where we have times and performance being recorded daily by drivers and workshop operatives and in addition we have laid the foundation to account for mileage, fuel and oil, parts and tyres, etc. So we are now ready to move on towards the completion of the most important document in the Flow-Line system—the monthly vehicle record of performance and cost—which I shall introduce in the next part.