IN SEARCH OF AUTOMATION

Page 28

Page 29

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

• It's now a year since Commercial Motor reviewed the progress of automated transmissions in trucks and buses (Engineer's Notebook, CM 29 September5 October 1988). Not surprisingly, there have been further developments, but the use of semiand fully-automated gearboxes in heavy trucks remains limited.

The obvious question is why? In many instances, while the gearbox manufacturers and truck builders have been keen to put evaluation units into haulage fleets, the development period from prototype to production unit remains a long one.

Another reason is the natural conservatism within the haulage industry. After all, a new, unproven system could be an expensive mistake, so why not let someone else make it? What's more, even the sophisticated electronics controlling the current generation of semiand fullyautomated transmissions can only do so much thinking for themselves.

They can't, for example, see the road ahead, so the on-board computers can only recommend a shift change based on what is happening on a particular section of road at that precise moment in time, and not 100 metres further on. To overcome this limitation manual overides are invariably employed, allowing the driver a say in the shift process.

PROFESSIONAL

On a more pragmatic note there will always be operators who, having paid for the services of a supposedly professional driver, do not see why they should not be able to perform perfectly adequately, and economically, on a manual box. Automation costs money. Unless there is a tangible benefit from using it — such as a reduction in downtime, or a saving in fuel — then the average operator will leave it, rather than take it.

It's worth noting that those manufacturers which do offer automated transmissions do not claim that they will make a good driver better. Rather, they are sold on the basis of being great "levellers": raising the standards of the less-proficient drivers in a fleet. In any case, the de velopment process continues unabated. During the past 12 months gearbox manufacturer Eaton and truck maker MAN have been busy applying automation to truck gearchanging in various degrees.

Eaton now has six automated mechanical transmissions (AMTs) on trial with halfa-dozen UK operators, including TNT, Inter City Transport and Christian Salvesen. Significantly they are all fitted to MAN tractors and, like the lesssophisticated semi-automated-mechanicaltransmission (SAMT), they are based on the popular Eaton Twin Splitter constantmesh manual gearbox.

CM recently drove TNT's AMTequipped 17.332F1'S tractor, and we were duly impressed (CM 6-12 July). AMT is the next step up from SAMT, having no clutch pedal (the clutch is actuated by a pneumatic servo through a conventional release system), and a gear selector console in place of the SAMT's up/down shift selector lever,

It also features an uprated electronic control unit (ECU) working on a 16-bit microprocessor with expanded memory. This interprets signals sent from various sensors, providing the "intelligence" to control the synchronisation of the constant-mesh Twin Splitter box, and operating it in a fully-automatic mode.

There is also an electronic throttle; effectively a "drive-by-wire" system which controls engine revs, eliminating the need for a mechanical link between the fuel pump and throttle pedal.

The driving process is simplicity itself. Before starting the engine, the gear selector must in neutral on the console. The driver then selects "Drive" — normally third gear. For hill starts there is a "Drive Low" which selects crawler. At this time the clutch is automatically disengaged and the throttle set at idle.

When the handbrake is released the clutch progressively takes up the load as the throttle pedal is depressed and power is applied to the truck. The ECU analyses the power demand and rate of acceleration and lets out the clutch accordingly, so moving off is always smooth with mini mum clutch slippage. lithe throttle is fully depressed when accelerating from rest, then the engine will reach near full power in each gear before an up-shift occurs (in the TNT MAN this normally happened at around 1,800rpm). Successive gears are selected until top gear (12th) is reached.

Each up-shift is accompanied by a sequenced clutch release and re-application, in conjunction with a dip in the throttle. In order to achieve the quickest possible changes when going up the box, the internal up-shift brake in the Twin Splitter is also briefly used. If the throttle is not fully depressed then the shift pattern is adjusted so the gears are taken earlier, improving fuel economy by using maximum torque rather than power.

On down changes. the system is virtually the same in that the clutch is disengaged then re-engaged, but this time the throttle dip is replaced by a "blip" (as required when double declutching on a normal manual box). If the rate of deceleration is great enough, the AMT box will automatically skip shift down.

As part of the AmT programme, when the exhaust brake is used downhill, the ECU automatically changes down an extra gear, allowing engine revs to build up, thereby getting greater retardation due to the increased back pressure.

FLEXIBILITY

For flexibility the driver can select "Hold" and make manual gear changes by means of a rocker switch.

Although the system has generated a great deal of interest, Eaton stresses that the six test trucks form part of a two-year evaluation programme, so AmT is unlikely to become generally available in the UK until at least 1991.

Obviously AMT has a lot of potential — not least in providing constant engine control across a wide range of engine conditions. Exactly how well it performs, however, will ultimately depend on the software which controls the gearchanging process. While it would be easy to programme the AMT microprocessor to a specific operation, like a regular night trunk run, a full production model must be capable of dealing with any road conditions at any time. Achieving this level of sophistication will take time. Neither would it be in Eaton's strategic interest to rush AMT into production so soon after SAMT has come fully on stream.

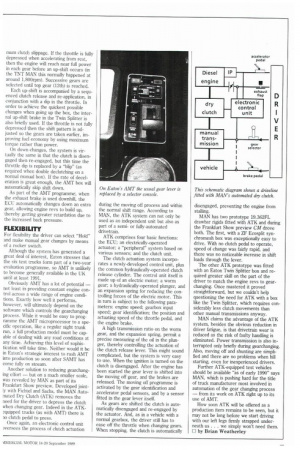

Another solution to reducing gearchanging effort — but on a much smaller scale, was revealed by MAN as part of its Frankfurt Show preview. Developed jointly with Fichtel and Sachs, the MAN Automated Dg Clutch (ATK) removes the need for the driver to depress the clutch when changing gear. Indeed in the ATKNuipped trucks (as with AMT) there is no clutch pedal to press.

Once again, an electronic control unit )versees the process of clutch actuation during the moving off process and within the normal shift range. According to MAN, the ATK system can not only be used as an independent unit but also as part of a semior fully-automated drivetrain.

ATK comprises four basic functions: the ECU; an electrically-operated actuator; a "peripheral" system based on various sensors; and the clutch unit.

The clutch actuation system incorporates a newly-developed control unit, plus the common hydraulically-operated clutch release cylinder. The control unit itself is made up of an electric motor; a worm gear: a hydraulically-operated plunger, and an expansion spring for reducing the controlling forces of the electric motor. This in turn is subject to the following parameters: engine speed; gearbox input speed; gear identification; the position and actuating speed of the throttle pedal, and the engine brake.

A high transmission ratio on the worm gear, and the expansion spring, permit a precise measuring of the oil in the plunger, thereby controlling the actuation of the clutch release lever. This might sound complicated, but the system is very easy to use. When the ignition is turned on the clutch is disengaged. After the engine has been started the gear lever is shifted into the moving off gear, and the brakes are released. The moving off programme is activated by the gear identification and accelerator pedal sensors, and by a sensor fitted in the gear lever itself.

As gears are shifted the clutch is automatically disengaged and re-engaged by the actuator. And, as in a vehicle with a normal gearbox, the driver still has to ease off the throttle when changing gears. When stopping, the clutch is automatically disengaged, preventing the engine from stalling.

MAN has two prototype 19.362FL drawbar rigids fitted with ATK and during the Frankfurt Show preview CM drove both. The first, with a ZF Ecosplit synchromesh box was exceptionally easy to drive. With no clutch pedal to operate, speed of change was fairly rapid, and there was no noticeable increase in shift loads through the lever.

The other ATK prototype was fitted with an Eaton Twin Splitter box and required greater skill on the part of the driver to match the engine revs to gearchanging. Once mastered it proved straightforward, but we couldn't help questioning the need for ATK with a box like the Twin Splitter, which requires considerably less clutch movements than other manual transmissions anyway.

MAN claims the advantage of the ATK system, besides the obvious reduction in driver fatigue, is that drivetrain wear is reduced as the risk of faulty handling is eliminated. Power transmission is also interrupted only briefly during gearchanging. Also, moving off and shunting are simplified and there are no problems when hill starting, even for inexperienced drivers.

Further ATK-equipped test vehicles should be available "as of early 1990" says MAN, which is pushing hard for the title of truck manufacturer most involved in automation of the gear changing process — from its work on ATK right up to its use of AMT.

How soon ATK will be offered as a production item remains to be seen, but it may not be long before we start driving with our left legs firmly strapped underneath us . . . we simply won't need them. 171 by Brian Weatherley