Shotts twenty-five years on target

Page 59

Page 60

Page 61

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

This company's assembly lines are as up to date as any in Europe. How has a sophisticated American engineering firm been able to make a success of a project in the heart of the Scottish coal fields? lain Sherriff reports from Lanarkshire

"AH KEN Whit wey it wis." Eddie Farquhar, maintenance fitter at the Shotts plant of Cummins Engine Company, is well qualified to explain why Don Cummins chose a hitherto relatively unknown Lanarkshire village to establish his engine assembly plant. The company celebrates its 25th birthday this week.

Eddie is Shotts-born and bred. He was maintenance fitter at what was the cotton mill, now occupied by Cummins. He is among its longest serving employees.

But Eddie was not to monopolise our round-table discussion. Frank Campbell, DFM, ex-Spitfire pilot and draughtsman, is Cummins design and liaison engineering manager; Dick Scott, a former colleague of Frank, is manager of customer services; Jim Hawthorne, ex-Merchant Navy Officer, is the organisation division manager; Dick Sweeny, an assembly line man, is an ex

miner; and Jim Boyd, another of Frank Campbell's former colleagues, is a turret operator.

All are long-service men who will soon qualify for a 25 years' service award. If Cummins follows British tradition there is a market for gold watches in Shotts.

According to these long-service men, Don Cummins had the choice of London or Shotts. Ed die believes that there could have been only one-choice. "We had Margaret Herbison, MP, pushing our case, and also the right labour force up here. There could be none b.etter," he argued. Dick Sweeny, the miner, agreed. "The coal mines here were being run down. There was plenty of labour coming on the market, and good labour, too. There's no more dedicated worker than a miner and no more grateful man than an exminer who finds himself working safely on the surface."

There were other more practical considerations in Don Cummins' calculations, however. Dick Scott took up the geograrhical point. "Shotts is equidistant from Glasgow and Edinburgh, connected by a good road — now a motorway — and a railway line ran past our front door then. At both ends of the road link there are air and sea ports." Jim Hawthorne made ano point. "Our first market was did earthmovers and they v assembling just along the E burgh road at Newhouse."

Frank Campbell took up running. "Shotts is in an aln identical geographical situa to the parent company'S plat Columbus, Ohio. We can re duce similar atmospheric co tions to the, Ohio plant in tests."

Frank, who was employe AEI Ltd, Motherwell, 26 y ago, was head-hunted by C mins as he fished on na Loch Leven. f'Poached migh a better word," said Frank, a knowing nod. Poached tainly applied to those wl Frank encouraged to leave and join him at Shotts.

How does a sophistic American engineering COMf make a success of a proja the heart of the Scottish fields? Training, perseveri and marketing are the ansv according to Dick Scott.

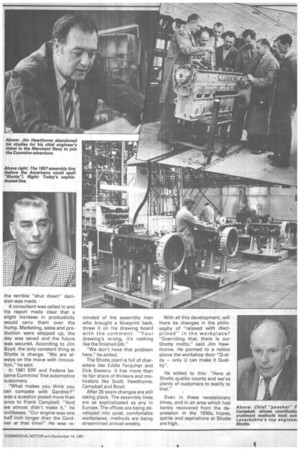

He explained: "Men v brought into the plant ani part of their induction cleaned the floors, opened ing cases, handled compon and then, after a period on work, they went on to forma sembly line training." le late Alex Kelly, who left tts for the Athens plant and in Greece recently, played a Jart in the training. He orgad evening classes, in the t after work. The men went g for two or three hours out pay — 50 per cent of the :force took advantage of the ntary scheme.

Drking overtime without pay of itself a phenomenon in land in the Fifties. There another at Shotts. Jim Boyd up the story. "We had no of demarkation. When a of material arrived from rica, an assembly crew got d about it and stripped it 1. The contents were re d and laid out in 'assemne' fashion. The engine was assembled with everyone playing a part. Including Don Cummins."

It became apparent that Don Cummins was the motivator. Men training without pay, no lines of demarkation and no redundancies. A recipe for today, perhaps?

His motivating powers were put to the test early on. He had received an order for 12 engines for Gibraltar, but had only four days to assembly. "We all buckled in," said Frank Campbell, 'Sand the job was finished bang on time. Don Cummins left to take a telephone call and returned a little dejected to tell us we had lost the order."

Nevertheless, the new employees had faith in their future. The first engine test bed had taken an outside contractor one month to install. Using their own resources, the Shotts men put in the second over a weekend.

In the beginning, the hourly rate at Shotts was three shillings and six pence or 171/2p, without any guarantee of overtime. Soon those who had to travel to the plant found it a financial strain. Unlike today's protracted negotiating procedure, the forthright men at Shotts asked the management to meet them all on the shop floor to hear the problem. Two weeks after the meeting they received a 25 per cent increase. There was neither militancy nor threat in the discussion. Just a statement of fact and a calculation to reach an amicable solution.

Men and management are proud of their industrial relations record at Shotts. "There has never been a long dispute here," said Jim Hawthorne. Dick Sweeny and Eddie Farquhar agreed. "We haven't lost seven days' production in 25 years," said Eddie. Note no reference to loss of wages — loss of production was the key. Dick Scott described the atmosphere at Shafts as "relaxed with discipline".

"Even now, with 1,200 people employed, we get over problems with no fuss and certainly no acrimony," he said.

From the early days when the plant produced five engines a week, production has grown to 38 a week. But there was a. purple patch. After seven years' production, Shotts was not paying and the lease was due for renewal. A decision had to be made by the parent board.

If commercial thinking had been the only consideration then Shotts would surely have closed and in the light of today's results that would have been a mistake. Uncharacteristically for America n s, the Cummins board allowed its heart to rule its head. They took the view that many of their employees had put their faith in Cummins and every avenue had to be explored before the terrible "shut down" decision was made, A consultant was called in and his report made clear that a slight increase in productivity would carry them over the hump. Marketing, sales and production were stepped up, the day was saved and the future was secured. According to Jim Boyd, the only constant thing at Shotts is change. "We are always on the move with innovation," he said.

In 1961 ERF and Fodens became Cummins' first automotive customers.

"What makes you think you can compete with Gardner?" was a question posed more than once to Frank Campbell. "And we almost didn't make it," he confesses. "Our engine was one half inch longer than the Gardner at that time!" He was re

minded of the assembly man who brought a blueprint back, threw it on his drawing board with the comment: "Your drawing's wrong, it's nothing like the finished job."

"We don't have that problem here," he added.

The Shotts plant is full of characters like Eddie Farquhar and Dick Sweeny. It has more than its fair share of thinkers and motivators like Scott, Hawthorne, Campbell and Boyd.

After 25 years changes are still taking place. The assembly lines are as sophisticated as any in Europe. The offices are being developed into quiet, comfortable workplaces; methods are being streamlined almost weekly. With all this development, will there be changes in the philosophy of "relaxed with disciplined'' in the workplace? "Overriding that, there is our Shotts motto," said Jim Hawthorne. He pointed to a notice above the workshop door "Q-ality — only U can make it Quality".

He added to this: "Here at Shotts quality counts and we've plenty of customers to testify to that."

Even in these recessionary times, and in an area which had barely recovered from the depression in the 1930s, hopes, spirits and aspirations at Shotts are high.