...Following the show we were able to get out on

Page 57

Page 58

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

the highway with two exhibits — a Kenworth and a Mack.

• The premium conventional (bonneted) truck enjoys a special place in the North American trucker's heart. It is coveted by the owneroperator who puts style ahead of Fuel economy — and most stylish of all is, arguably, the Kenworth W900L.

I. stands for Long-nose, and when it was introduced a couple of years back the big Kenworth represented a return to the grand old days of American trucking.

The re-introduced KW was the right product at the right time for Kenworth and has been extremely popular. It has been updated, too, to give it a better ride and a more manageable turning circle, But it is fighting newly introduced competition from Freightliner and Peterbilt, as well as a new competitor in the Mack 0.600.

Where the Kenworth is designed from the ground up as a proprietary powertrain truck, with only the cab, frame and assembly by Kenworth, the Mack is nearly all in-house. The exceptions are the Eaton axles. How do the two compare?

American conventionals are designed for the long haul. Most operators expect around seven years' life, and as much as 193,000km (120,000 miles) a year. They look For an in-frame overhaul at around 965,000km (600,000 miles) and then expect to run the truck for another several hundred thousand before replacing it. So durability and reliability are paramount, driver comfort used to be a low priority with the big fleets, but not any more.

Conventionals are quite different from Europe's cabovers (forward. control trucks). For a start, you sit in a different place relative to the steer axle and wheels, so you must learn to look at the rood differently. And you have to take corners in a new way too.

Driving these two, we were pulling 14.6m (48ft) trailers with the sliding axles set all the way back. The conventionals have much improved steering over those 10 years ago, but that old country music title still applies: Give me 30 acres and turn this thing around. Corners have to be taken with the co-operation of other road users — behind, alongside and in front.

A major problem is the mirrors. Regulations say that the glass has to be flat, so all truckers fit wide-angle spot mirrors. But unlike the European-style glass, the image in these curved mirrors is so distorted that it's difficult to sort out what is happening way back there at the trailer wheels. Add that to the unusual seating position and you have cause for caution.

We didn't see a sticker price on the Mack — twos a newly produced prototype. But the Kenworth will set you back $145,000 (£80,000).

The Kenworth was driven on the Pacific Coast and the Mack on the Atlantic, so conditions were quite different. However, whether climbing the western mountains or cruising Florida's beach cities, both trucks performed effortlessly—as they should with over 2,170Nm (1,600lb ft) of torque on tap. The Mack was the most dramatic, rearing up from under the trailer as the torque was applied through the lower gears in the 18-speed Mack transmission. The effect was accentuated by the torque reaction in the frame, which caused the left front corner to lift higher than the right.

The Kenworth was also extremely impressive. The Caterpillar 460 has a gutsy torque curve at the bottom end, hanging in really well as the revs drop to 1,000. The Mack vee-eight, with its torque peak at 1,300rpm, does not have the same snappy response, so while the performance is awesome in both, the Kenworth is easier to drive.

Neither truck is a slouch. With 18-speed transmissions in both they can be kept way up in the horsepower so whole gears are all that's needed through the first lever positions. After the rangechange, splits get the absolute best performance, but the torque is so monumental they're not really necessary. The transmisisons are all constant mesh, so gearshifts are a matter of timing and precision.

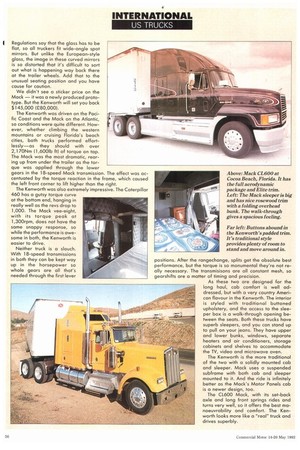

As these two are designed for the long haul, cab comfort is well addressed, but with a very country American flavour in the Kenworth. The interior is styled with traditional buttoned upholstery, and the access to the sleeper box is a walk-through opening between the seats. Both these trucks have superb sleepers, and you can stand up to pull on your jeans. They have upper and lower bunks, windows, separate heaters and air conditioners, storage cabinets and shelves to accommodate the TV, video and microwave oven.

The Kenworth is the more traditional of the two with a solidly mounted cab and sleeper. Mack uses a suspended subframe with both cab and sleeper mounted to it. And the ride is infinitely better as the Mack's Motor Panels cab is a newer design, too.

The CL600 Mack, with its set-back axle and long front springs rides and turns very well, so it offers the best manoeuvrability and comfort. The Kenworth looks more like a "real" truck and drives superbly.