tb

Page 71

Page 72

Page 73

Page 74

Page 75

Page 76

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

hPpon

CmCOMPARISON

oy Graham Montgom erie

photographs by Dick Ross

THE eight-wheeler is a traditionally British truck so what more topical choice could there be for CM 's British Vehicles for World Markets number. In Britain the four-axle machine has long found favour with the tipper men. So for this group test we assembled three tippers from the ERF, Leyland and Seddon Atkinson ranges. Unfortunately, Fodens were unable to lend us one.

The trucks were put through their paces in a typical environment by courtesy of Mr Len Matthews of the Heavy Transport division of English China Clay in Cornwall, where we fitted the vehicles into the fleet for a normal working schedule.

Performance and economy

FITTING into a typical on/ off-site operation using one of the English China Clay quarries, we loaded up with overburden and shifted it to where the company is landscaping the area— in all a round trip of just over 6km (about 3.8 miles) including slippery slopes on site and steep gradients on the road section. The best fuel consumption figures were returned by — surprise, surprise—the 6 LXB ERF. For our test, which rarely gave the driver the chance to reach top. gear, even unladen, the ERF returned a figure of 54.4 lit/100km (5.2mpg)— excellent considering the operating conditions which required the use of bottom gear for long periods on some of the more arduous sections.

One section of the off-road part of the exercise took us up a gradient of about 1 in 6 on a slippery clay surface. At one Lime or another both the ERF and the Seddon Atkinson had to reverse back down this slope and dump part of the load to be

continued overleaf

able to reach the top.

The Octopus got away with it partly because of the crawler gear in the Fuller box and partly because the Leyland ran at a slightly lower gvw than the other two.

All the trucks were loaded with seven buckets by Case or Komatsu shovels so in relation to its very light kerb weight the Leyland had a distinct advantage in hill-climbing ability by having a lower gross weight for the same payload. The average payload was in the region of 19/20 tonnes, varying from trip to trip depending on how much of the previous load had stuck in the body.

The Gardner engine in the 'ERE displayed its usual strong slogging ability in the lower engine speed range although, as I mentioned, it had to admit defeat on occasions.

The turbocharged engine in the Octopus stood up well to the conditions, being helped by the Fuller's crawler gear. The overall fuel consumption for the exercise was 59.2 lit/100km (4.8mpg). In general, the Leyland / Fuller combination seemed better matched than the David Brown coupled to the Gardner and Cummins units.

In the ERF this was partially masked by the willingness of the Gardner to accept a low engine speed without the need for an extra gear change.

The Seddon Atkinson proved to be the heaviest on fuel when we added up the figures. The NH 220 Cummins returned 72.1 lit/100km (3.9mpg)— thirsty when compared with the other two over the same operating conditions. The Oldham truck suffered the most on the steep gradients because the body was very prone to retaining a lot of the previous load in the corners and this had to be shifted with a spade every other trip. As it was, the Seddon Atkinson ran consistently at around 750kg (15cwt) over its normal payload with no benefit to the operator.

The differing outputs of the various engines did not seem to make very much difference on their own. For example, running at the 30-ton limit, the 5.2kW/ tonne (7.1 bhp/ton) of the Octopus did not endow it with any greater performance or climbing ability than, say, the 4.5kW/tonne (6.1bhp/ton) of the Gardner-powered ERF. Where any performance difference was apparent it was in the match between the gearbox and the engine characteristics, and in this sphere the Leyland did extremely well.

Driving impressions

THE GARDNER engine demands a different driving technique by virtue of its lazy engine speed and its slogging ability is renowned, The ability of the engine to hang on at around 900/1,000rpm proved very useful with the ERF on a number of occasions during the test.

The noise level in the B Series cab with this engine option should not give the drivers any cause for complaint. Even when hurtling around at a prodigious 1,850rpm, the engine noise stayed very much in the background.

However, one thing which did come in for a fair amount of criticism on the ERF was the pedal arrangement, although in the past I have been able to single out the pedal positioning on ERFs for praise. But with our test model, although the positioning was the same the operating angles and pressures were vastly different. The throttle pedal action in particular took some getting used to.

The braking was safe and sure but there was a fair amount of leading rear-axle hop under braking when the truck was empty.

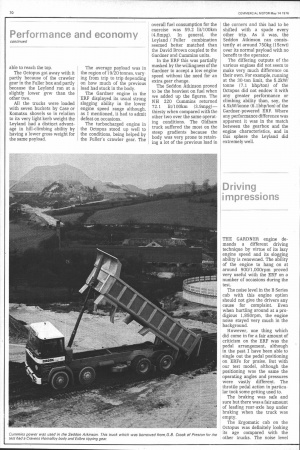

The Ergornatic cab an the Octopus was definitely looking its age compared with the other trucks. The noise level

Right: The lightest of them all was the Leyland Octopus which weighed in at 9.8 tonnes (9tons 13cwd complete with Edbro body and gear.

was much higher and Leyland still insists on using those terrible push/pull windows. I've never been given a satisfactory explanation why Leyland dropped the old "quickrelease" lever system which was the best on the market.

The steering was excellent for my tastes although I would expect that many drivers might find it too light for road operation. On our test, with a great deal of shunting about, this ' ease of steering was much appreciated. The rapid gear selection of the Fuller box was a useful asset especially when compared with the more ponderous shift of the David Brown unit.

For ease of getting in and out, the Leyland cab was the easiest, but this was due to the low mounting of the cab rather than the cab design itself. With the "economy model" interior, the poor positioning of the instruments and the noise level, the Octopus fell down on this aspect of the operational trial.

The most notable feature of the Seddon Atkinson from the driver's point of view was the need to adapt to the "backwards" shift pattern for the eight-speed David Brown gearbox. Although both the ERF and the Seddon Atkinson used the identical box, the latter truck has first gear towards the driver and back with the other gears following in anticlockwise sequence. The ERF, however, used a conventional shift pattern with the first gear being away from the driver and forward and so on.

Swopping from one vehicle to another during the course of a CM trial is something that we often have to do and adapting to different gearboxes and different shift patterns is all part of the job. However, it does make it more difficult when the identical gearbox on two makes of truck has a reversed shift pattern—and this could cause problems in a mixed fleet.

The Cummins unit is not, exactly renowned for being a quiet engine although the installation in the Seddon Atkinson is a gotid one with the greater proportion of the noise being prevented from entering the cab. The well laid out instrument panel came in for favourable comment as did the pedal positioning.

A driver using this truck on a relatively short round-trip operation would find the high cab a nuisance to clamber in and out of frequently, but otherwise we formed a favourable driving impression of the Seddon Atkinson.

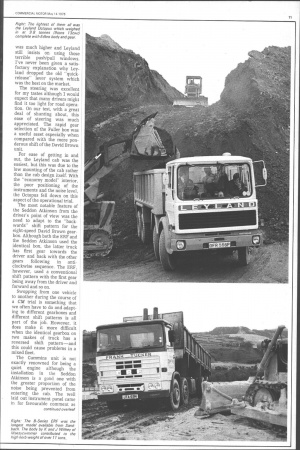

Tipping

ALL the machines taking part in our test were fitted with Edbro tipping gear, but varying in shape and size. All were front mounted, with the ERF having a twin-ram unit while the other two trucks used a single-ram system. Although all three trucks utilised the same tipping controls, their positioning varied considerably.

On the ERF the controls were situated on the left side of the driver's seat near the rear of the cab. Moving ,he panel further forward would have made it easier for the driver, but on the B-Series the parkbrake control would be in the way. On the Octopus the positioning was just about ideal, but this was only by virtue of having the park brake control situated out of comfortable reach on the front of the instrument cowl. You can't have it both ways.

The controls were placed to the right of the driver's seat on the Seddon Atkinson—satisfactory as long as you looked where you were going when getting out of the cab.

The tipping part of the exercise was carried out with no problems with any of the trucks although it was noticeable how the twin-ram system on the ERF was prone to bend like a couple of bananas if the ground was not spirit-level even. The single-ram systems did not share this characteristic. Otherwise there were no complaints about stability for any of the three trucks.

Maintenance and accessibility

FOR COMMENTS on the maintenance and accessibility side of the three test trucks, we asked the workshop staff of English China Clay for their opinions.

The tilt cab on the ERF allowed excellent access to the Gardner motor and this received favourable comment. The pipework neatly recessed into the main frame longitudinals was also singled out as being an excellent design point compared with the haphazard and unprotected systems on some of the other vehicles in the workshop.

Two points were critisized on the ERE. One was the low-mounted tap in the bottom hose which was right in line to be sheared off in the rough and tumble of site work. The other point concerned the lack of an inspection hole in the brake back plates on the front axle.

The fitting staff claimed that the underslung springs would be easy to get at even if burning out the pins was required to change the assembly. The clamp bolts on the spring hangers, however, were so positioned that a turn of only a few degrees at a time was possible with an openlended spanner; it was impossible to get a ring spanner anywhere near the nut.

The Octopus came in for some stick from the workshop staff. Their comments were directed mainly at the poor access to the power unit even with the cab tilted (a long job on the Leyland compared with the other two and only a small angle of tilt at the end of it). Although the hatch in the cab provides some degree of access to the engine, there was really no comparison and the fitters were especially criticial of the lack of reasonable access to the fuel pump.

After critizing the Octopus heavily on this point, items which brought favourable comment were the frame and the vertical exhaust. The strengthening of the frame in strategic places rather than all over was appreciated as providing adequate frame strength without unnecessary weight. Owing to the dust problem on many sites, operators like the vertical exhaust arrangement as it does not blast the dust around as with a conventional low level system.

With the unusual bogie on the Octopus, the number of bolts and brackets was commented on.

The workshop staff were not impressed with the accessibility to the T6 design especially in the spring shackle pin region where they assumed that the brakes, backplate and hubs had to be removed before the pins could be replaced. I contacted Leyland on this point and the pins can be extracted without dismantling the hubs but a special tool is required.

Engine accessibility on the Seddon Atkinson was corn parable with the ERF by means of an hydraulically tilted cab. What to do with the gear lever when tilting the cab had different solutions with these two trucks. On the ERF the gear lever remained fixed to the engine with a spring-loaded rubber gaiter to take care of the sealing. On the Seddon Atkinson they do not need to bother with such an arrangement as the gear lever stays with the cab after splitting at a ball and socket joint.

In general, it was felt that the accessibility on the SA was marginally inferior to that of the ERF. The colour-coded plastic piping was complimented although the workshop staff were very critical of the "S"cam bushes on the brakes, which were made of plastic— they much prefer needle rollers.

The only problem here is that Seddon Atkinson buy the axles from Eaton complete—so they don't have any control over this feature.

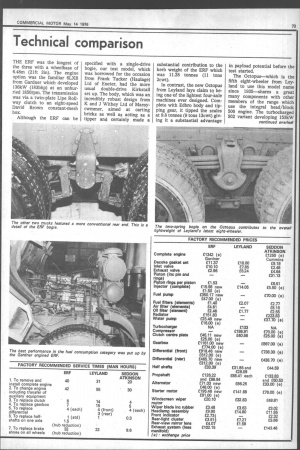

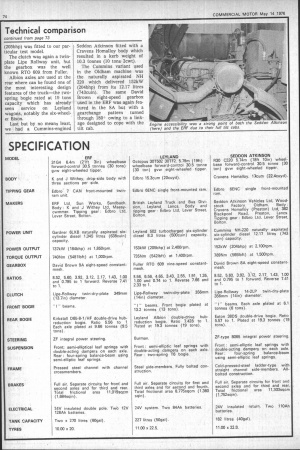

Technical comparison

THE ERF was the longest of the three with a wheelbase of 6.48m (21ft 3in). The engine option was the familiar 6LXB from Gardner which developed 136kW (183bhp) at an unhurried 1850rpm. The transmission was via a twin-plate Lipe Rollway clutch to an eight-speed David Brown constant-mesh box.

Although the ERF can be specified with a single-drive bogie, our test model, which was borrowed for the occasion from Frank Tucker (Haulage) Ltd of Exeter, had the more usual double-drive Kirkstall set up. The body, which was an incredibly robust design from K and .1 Withey Ltd of Maesycwmmer, aimed at carting bricks as well as acting as a tipper and certainly made a substantial contribution to the kerb weight of the ERF which was 11.28 tonnes (11 tons 2cwt).

In contrast, the new Octopus from Leyland lays claim to being one of the lightest four-axle machines ever designed. Complete with Edbro body and tipping gear, it tipped the scales at 9.8 tonnes (9 tons 13cwt) giving it a substantial advantage in payload potential before the test started.

The Octopus-which is the fifth eight-wheeler from Leyland to use this model name since 1935-shares a great many components with other members of the range which use the integral head/block 500 engine. The turbocharged 502 variant developing 153kW (205bhp) was fitted to our particular test model.

The clutch was again a twinplate Lipe Rollway unit, but the gearbox was the well known RTO 609 from Fuller.

Albion axles are used at the rear where can be found one of the most interesting design features of the truck-the twospring bogie rated at 19 tons capacity which has already seen service on Leyland wagons, notably the six-wheelei Bison.

Last but by no means least, we had a Cummins-engined Seddon Atkinson fitted with a Cravens Homalloy body which resulted in a kerb weight of 10.3 tonnes (10 tons 2cwt).

The Cummins variant used in the Oldham machine was the naturally aspirated NH 220 which delivered 152kW (204bhp) from its 12.17 litres (743cuin). The same David Brown eight-speed gearbox used in the ERF was again featured in the SA but with a gearchange pattern turned through 180c owing to a linkage designed to cope with the tilt cab.