Combines qt

Page 58

Page 59

Page 60

Page 61

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

By ty with Economy A. J. P. WILDING

AM I Mech E, MIRTE

ALTHOUGH not following the main trends at last year's Earls Court Commercial Motor Show—tilt cabs, vee engines and so on the introduction of the 13:Four by Seddon at that event was noteworthy because the model was the outcome of a considerable amount of work aimed at producing a quality vehicle at a relatively low price. The vehicle is certainly well designed, and our test of the 14 ft. /I in.-wheelbase version has shown it to give good fuel consumption coupled with a lively performance for a vehicle grossing jushover 13 tons. Handling also was commendable, with light steering and well-placed controls, and the general "feel of the brakes on the road was excellent—mainly because of an almost complete absence of lag in the air-pressure system. This led me to expect very good results on the brake tests, but although Tapley-meter readings of around 65 per cent were obtained, the actual stopping distances were not good by present-day standards.

A lot of the credit for the good fuel consumption must go to the Perkins 6.354 diesel engine used in the 13:Four. This is the high-rated version, with a maximum net output of 114 b.h.p. at 2.800 r.p.m. and maximum net torque of 254 lb. ft. at 1,250 r.p.m. The power and torque characteristics are well matched to the David Brown 560/2 live-speed constant-mesh gearbox developed specially for the 13:Four. The engine and gearbox are mounted as a unit, the drive being taken through a 13 in.-diameter strapd ri ve clutch.

An important feature of the 13:Four—and the main one in helping to keep down the selling price—is the adherence to a rigid specification with only two options in the mechanical units: a two-speed rear axle instead of a singlespeed unit, and power steering. There are also a number of optional equipment items such as heater, windscreen washers and automatic chassis lubrication, but the aim has been to produce a vehicle with few variations. As well as the 14 ft. 8in.-wheelhase chassis tested, there are three other wheelbase dimensions available for goods chassis-9 ft. 3 in. and 12 ft. 6 in. for tippers, and a 16 ft. 9 in. Wheelbase chassis for 23 ft. or 24 ft. bodies; in addition, there is an 8 ft.-wheelbase tractive unit. The tractive unit is designed for a gross train weight of 18 tons compared with the 13 tons gross-weight rating of the rigids. On all five versions of the 13:Four, identical components are used where possible, and the layout of these is identical at the forward end of the chassis, including brake pipes, battery mounting and fuel tank mounting.

The same cab is fitted to all versions, this being called the Sup'a-Cab, built for Seddon by Motor Panels Ltd., of Coventry. Internal fittings of the all-steel cab are to a good standard and access is by steps forward of the front wheels. Overall width of the cab is 7 ft. 6 in. and the interior width at waist level between the doors is 6 ft. 4 in.

The gear ratios as in the test vehicle are the only ones available, and although originally there• were alternative rear-axle ratios of 6-16 and 6.83 available it has been found that-the former is adequate for all requirements and the 6.83 to I option has been dropped. For the two-speed-axle option an Eaton 16802 driving head is used in the Seddon • axle and the only ratios available are 5.57/7.70 to I.

For the tests, the 13:Four was loaded with concrete-filled steel boxes weighing 8 tons 18-5 cwt. which, with two men in the cab, brought the,gross weight to 725 cwt. over the designed 13 tons figure. The load was evenly distributed over the platform and gave front arid rear axle loads of 5 tons .1-5 cwt. and 8 tons 5.75 cwt. respectively. This overloaded the front axle by 1.5 cwt., but the rear axle was well within its capacity of 9.5 tons.

Fuel conSumption tests were carried out first on a sixmile circuit of good-class and fairly level roads in Chadderton, a residential area north of Manchester. Because of the need to go through six sets of traffic lights plus the negotiation of a busy roundabout. the circuit was not conducive to good fuel consumntion figures. In fact, on each of the three runs on the test the vehicle had to stop at four sets of lights. The total time of these stops was just over a minute on each of the test runs, during which time the engine was left idling.

Figures obtained (see results table) can therefore be taken as the worst that could be expected, and for long-distance operation it would not be unreasonable to anticipate a consumption figure in the region of 14-15 m.p.g. On the high-speed run, which was carried out at the end of the day on the M62 on the outskirts of Manchester, the consumption figure was again worsened by traffic conditions. The roundabouts at each end of M62 were fairly congested, and the fairly sharp inclines on the section of the motorway which goes over the Manchester Ship Canal brought the speed down to around 40 m.p.h., so the average speed of 45 m.p.h. attained was quite good in view of the 55 m.p.h. maximum speed of the vehicle. Consumption will obviously have been affected by the conditions, and without hold-ups I would have expected 12.5-110 m.p.g. rather than the 12-0 m.p.g. obtained.

Acceleration tests showed the 13:Four to have a lively performance in its class. A help in the through-the-gears runs was the easy gearehange. Flexibility in direct-drive was very good indeed and no distress was apparent when pulling away from around 9 m.p.h. in top gear.

As I said earlier, the general feel of the brakes was excellent, but this was not -confirmed by the braking tests. It is hard to find a reason for this, as the test vehicle had done more than 5,000 miles before the tests were started so the linings were well bedded in (they had not been changed before the tests) and the brakes had been adjusted. It is reported by Seddon that in the development of the 13: Four the braking effort was cut down because the brakes were originally too fierce. This is an understandable move, as the big difficulty in designing brakes is that they should be adequate when fully laden and not dangerous (through locking all the wheels) when unladen.

The balance between the frontand rear-wheel braking was very good on the 13:Four and there was no marking of the road at all, except on one of the stops from 30 m.p.h. when the offside rear wheels locked for the last 6 ft. or so. More effort could be applied to the brakes to reduce the stopping distances without bringing on wheel locking. Tapley-meter readings of around 65 per cent from both 20 and 30 m.p.h. showed quite adequate maximum deeelerations, but these appeared to be at the beginning of the stops; afterwards the deceleration tailed off. This is, no doubt, why the brakes felt good when used normally.

-Following the brake tests the vehicle was taken to Buck

stones Road, Shaw, a hill which is 1.'75 miles long and has an average gradient of 1 in 12, for hill-climbing tests. A full-throttle ascent was made in the good time of 7 min. 12 sec., during which time the lowest gear used was second, for 4 min. 16 sec., and the minimum speed was 8 m.p.h. Ambient temperature at the time of the test was 13°C (56°F) and the engine-coolant temperature at the start was 68°C (155°F).

After the climb the radiator filler cap was removed to check the increase in temperature, but the expansion of the coolant caused a large amount to gush out. It was not boiling--I know this because it poured over my hand—but because of the lower level of water it is not possible to say that the temperature reading of 86°C (187°F) obtained was absolutely accurate. The thermostat was definitely open, as the dash-mounted temperature gauge indicated about 190°F and the test was enough to show that the cooling system has adequate capacity.

Brake Fade Test

A descent of the hill was made to assess brake fade; for this the footbrake was applied to keep the speed of the vehicle at around 20 m.p.h. The time taken for the run down the hill was 4 min. 26 sec., and at the bottom a maximum-pressure stop from 20 m.p.h. produced a Tapleymeter reading of 33 per cent. It may appear that the drop of 32 per cent from the Tapley reading on the cold-drum brake tests is excessive, but this is a particularly severe fade test—even by our usual standards----and by the time the vehicle had reached the bottom the linings and drums were really hot; there was a very strong smell from the heated linings and a good deal of squeal set up towards the end. It is unlikely that the brakes will receive this sort of treatment in any operating conditions, and I would say that no trouble should be experienced with fade.

Returning up the hill again, stop-and-start tests were carried out on the steepest section, which has a gradient of 1 in 6-5. When facing up the hill an easy restart was made in bottom gear and when facing down a restart up the hill in reverse was made with equal ease. In both conditions the handbrake held the vehicle easily.

Whilst operators will find the Seddon 13:Four a worthwhile vehicle to run from the points of serviceability and fuel economy, drivers will find little to complain of if they are allocated this model. Even though the front axle was carrying more than 5 tons the steering was reasonably light. This was because the steering is fArly low geared, requiring 6-75 turns from lock to lock, which itself resulted in the need for quick work on taking sharp corners. There was no feeling that power steering would be of any advantage on the layout as in the test vehicle, but I can see advantages with this option with a higher-geared steering box. The gear-change action was also very good, with the gear-change lever convenient to hand and light in use.

lightness was, in fact, a feature of all the controls, applying also to the clutch pedal (even without hydraulic assistance) and the brake treadle. I found the driving position very good. The seat has fore-and-aft adjustment only, but the windscreen is deep enough to make vertical adjustment unnecessary on the score of forward visibility. The steering wheel was conveniently placed for me and even without vertical adjustment of the seat, drivers should be able to get used to its location.

1 found all-round visibility good, but the speedometer and instruments were not easy to read because, apart from being located near the centre of the dash, the panel is well back from the windscreen. Located below the instruments are switches for lights and so on, and these are easy to reach. The main-beam and dip-beam selector is on a stalk at the right-hand side of the steering column with the switch and warning light for the direction indicators. And whilst these were within easy reach, the warning light was rather unobtrusive and I found myself travelling some way with the indicator still going. I noticed on a new vehicle at the factory, however, that the stalk was positioned farther round the column, which should make the light more noticeable.

The cab is a well-made unit and has every appearance of being robust; there were no draughts and there was complete freedom from rattles. Adequate space is provided for storage of papers and small articles on shelves formed into the top of the facia, and the large swivel windows in both doors provide adequate ventilation in all circumstances. The rear-view mirrors are mounted low down—they are visible through the swivelling windows—and this takes some getting used to. After driving vehicles recently with extra large mirrors the ones fitted to the 13:Four appeared rather small and inadequate.

Access to the cab is easy, although the first step height at 2 ft. 3 in. with the vehicle unladen is rather high. However, well-placed grab handles are a useful fitting. And as it rained for most of the day of the test (the roads were dry for the brake tests) the use of 20 in. wipers, which cleared almost all the large windscreen, was appreciated.

In the unladen condition, the 13:Four handled like a private car. The suspension was reasonably soft, helped by the extra-long springs fitted at front and rear, and also by the use of slipper-ended rear springs giving a degree of variable rate because of the slipper-end bearing on a curved surface. When fully laden the ride was extremely good.

In general the 13:Four was a most pleasant vehicle to drive but I would criticize the degree of noise in the cab. When running at 40 m.p.h. and above, conversation was difficult, and I feel that increased sound lagging is required.

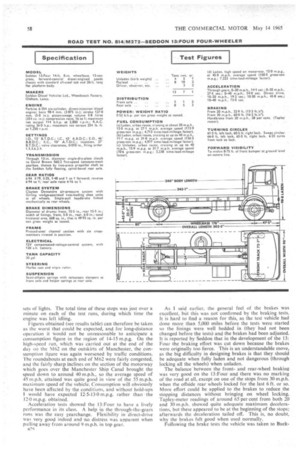

Maintenance of the Seddon 13:Four should provide few problems as there has been a good deal of attention paid to access to the various units. The engine is set fairly low in the frame. but removal of the engine cover gives a good degree of access to the top end of the unit and there is plenty of space between the engine and chassis frame to allow a fitter good access from underneath.

Taken all round the Seddon 13:Four is a vehicle with a great deal to recommend it to any operator. As well as operating economies, the standardization aimed at and attained by Seddon will help in the supply of spare parts. But likely to be most appreciated by operators is the price. The 14 ft. 8 in.-wheelbase chassis tested has a basic list price with cab of £1,827. The heater unit and spare wheel and tyre as on the test vehicle add £18 and £34 respectively bringing the total price of the chassis'cab to £1,879. Cost of the 20 ft. flat-platform body with full-height headboard by Pennine Coachcraft Ltd. is £149. making the total price of the vehicle-as tested £2,028—and very reasonable too.