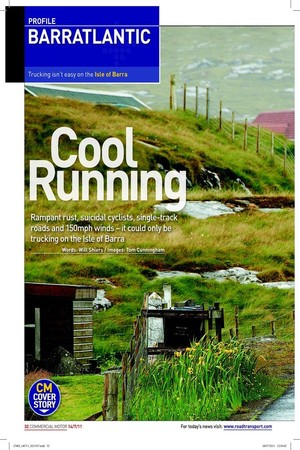

Rampant rust, suicidal cyclists, single-track roads and 150mph winds – it could only be trucking on the Isle of Barra

Page 26

Page 28

Page 29

Page 31

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

Words: Will Shiers / Images: Tom Cunningham

As far as haulage operations are concerned, Barratlantic’s doesn’t appear to be particularly complex. It delivers ish from its processing plant to the market in Glasgow, a journey of less than 200 miles, has a leet of modern trucks, a team of skilled drivers and reliable fridges. What’s so challenging about that? Well, unfortunately for Barratlantic MD Donald MacLean, there’s an obstacle between the plant and the market – 100 miles of Atlantic. It means that every journey either starts or inishes with a ive-hour ferry crossing and that’s just one of the many challenges of running a leet on the Isle of Barra.

The Isle of Barra is the southern most inhabited island in the Outer Hebrides. Beautiful and remote, it has a population of just 1,200 people. Operating trucks this far from the mainland has deinite disadvantages. The local VOSA test centre, truck dealers and CPC training course provider are all an eight-hour drive away. But every cloud has a silver lining, because that’s also how far you have to drive to see your irst VOSA road-check, speed camera, MSA and trafic warden.

Ninety-nine per cent of Barratlantic’s work involves ish. It catches it, processes it, then delivers it to customers on the mainland. The chilled and frozen product is loaded at the processing plant, before being carried over several miles of single-track road to the port of Castlebay, where the trucks board the ferries for their ive-hour crossings to Oban on the Scottish mainland.

The ferry operator is government-owned Caledonian MacBrayne. It runs two vessels on this particular route, one leaving the island early in the morning and the other mid-afternoon. It costs £700 per truck, and Barratlantic has at least one vehicle on every crossing. “Until three years ago we were charged £1,100 per truck,” says MacLean, “but this changed in 2008 when the Road Equivalent Tariff (RET) was introduced.” RET involves lowering ferry fares so they are in-line with the cost of travelling an equivalent distance by road in an attempt to boost economic growth on the islands.

Considering the price of the tickets, you might think the drivers get treated like royalty, but far from it. For each crossing they get a £5 voucher, which according to driver Archie McNeil isn’t even enough to buy a meal. Only one of the ferries has a drivers’ lounge – a small room with a portable television. It doesn’t even have a kettle.

“If you ask me, it’s an insult,” says MacLean. “If the ferries were operated by a private company, I’m sure the service would be better. You need to remember that these drivers can spend 30 hours a week on the ferry, which in some cases is longer than the crew. They even have to use the ferry when they go on holiday!” Having said this, the service is improving. In the past, says MacLean, services would be cancelled or delayed with no prior notice. “In the last year this has changed, and they are keeping us well informed.”

Inevitable delays

Some delays are inevitable: the weather in this remote part of the world can be particularly severe. Winds in excess of 100mph are not uncommon, and have been as high as 150mph. Needless to say, the last place you want to be in these conditions is on a ferry in the Atlantic.

Driver Alister MacNeil says he’s experienced some rough conditions in his 20-plus years of driving for the irm, and has even seen a truck tip onto its side. The week before we visited Barratlantic, the Volvo pictured here suffered some front-end damage on the ferry when a truck with a faulty handbrake rolled into it during a rough crossing.

“Bad weather is a nightmare for us,” says MacLean. The irm works to extremely tight deadlines, and any delays can be costly. The ferry docks in Oban at 2.10pm, and the trucks have to be in Glasgow for 6pm in time for the ish to be loaded into customers’ vehicles for their onward journeys to all corners of the LTK and Europe. If they miss their connections, the Barratlantic trucks have to wait 24 hours. MacLean says life would be a lot easier if the ferry docked an hour earlier.

To date, the longest delay has been four days, which was caused by exceptionally bad weather. “That’s a long time to be sitting in a truck with a perishable load,” he says.

Barratlantic’s roadgoing leet (it also operates seven ishing boats) consists of nine vehicles: three artics (two Volvo FHs and a Scania R-Series), a pair of 18-tonners (Volvo FLs), three 7.5-tonners (Mitsubishi Canters) and a rigid tanker (ERF EC6) for local fuel deliveries.

“The heavy trucks all used to be Scanias,” says MacLean, “but we started buying Volvos because that’s what the drivers wanted.” All three tractors are maintained by the Glasgow-based dealers who supplied them, while the rigids are looked after by CMS.

The Mitsubishis are mainly used on the island and are perfectly suited to the conditions. Of the island’s 14 miles of well-maintained roads, more than half are single-track.

In the past, Barratlantic ran its trucks for ive years, but these days tends to keep them for seven. Any longer than that is dificult considering the incredibly harsh conditions under which they operate.

While annual mileages might be low, frequent contact with salt water (on open ferries) takes its toll. It’s the same story with the trailers, which last for a similar length of time.

The backbone of the Barratlantic leet is its stable of Gray & Adams reefers, all powered by Carrier Transicold fridges. The most recent addition to the leet is a highcapacity Vector 1850 multi-temperature refrigeration unit, which MacLean says is well suited to remote island life because it uses an electric generator rather than being belt-driven direct from a diesel engine. As a result, it has considerably fewer serviceable parts, meaning less downtime, lower maintenance costs and enhanced durability. The fridges are maintained 26-weekly by James Hogg of Cambuslang, a long-time Carrier Transicold service partner. MacLean has only positive things to say about the fridge manufacturer, which he has worked with for two decades. “In 20 years of using their fridges, we haven’t lost a single load,” he says.

The only haulier in the village

In addition to the reefers, the irm also operates a curtainsider and two lats. These are used for carrying numerous other products to, from and around the island. Because Barratlantic is the only haulier on the island, it is often called on to deliver other items. As well as perishable loads, it carries parcels for TNT and Parcelforce, farm machinery for islanders, and even takes scrap cars to the mainland.

As if navigating single-track roads in an artic isn’t bad enough, Barratlantic drivers also have to deal with tourists. In the summer months, the island’s population swells from 1,200 to more than 4,000. “And unfortunately most of them seem to be cyclists,” says McNeil.

Another more recent problem has been the introduction of the Driver CPC. “It’s going to be costly,” complains MacLean, “but unfortunately the government doesn’t think about this sort of thing. Our closest course is eight hours away. So that’s a day to get there, a day at the course, and then a day to get back. I think a lot of folks on the island won’t bother, and will let their licences lapse.” One problem Barratlantic doesn’t face is a driver shortage. As well as being incredibly skilled, the company’s drivers are extremely loyal, and MacLean hasn’t had to recruit since the 1980s.

“Although the job has its downsides, I wouldn’t want to do anything else,” says McNeil. “I’d far sooner be sitting on a ferry for ive hours than parked-up in a trafic jam on the M25.” n