ROADTEST HMO SH283KA

Page 38

Page 39

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

• ACCELERATION

An early indication of the SH283KA's lack of pace came during acceleration tests. With this power-to-weight ratio we were not surprised that the Hino was unable to accelerate through the gears from 64 to 96km/h in a measured 1.6krn (one mile), although the Volvo PL10 just managed to do so in 78 seconds. The SH283KA took over 76 seconds to accelerate from 48 to 80kinth and was always going to struggle over the distance at the higher speeds.

In contrast, the FL10 and the Renault G290 (which manages to produce 22% more torque at a much lower engine speed) both took just 47 seconds. The Scania P92M which, with a 66.61cm/h (41.4mph) overall average speed, is the slowest of the Hino's direct competitors, was still quicker through the gears by some 13 seconds.

Engineering diagrams produced by HCV for type approval show the EP100 to have a long, almost fiat torque plateau that provides in excess of 940Nm between 1,000 and 1,650rpm.

Over mixed A road running at the 40 and 50mph (64 and 80km/h) limits, 7th and 8th gears are needed to keep the engine speed near the top of the rev counter's 1,000-1,800rpm "green" economy sector, where there is plenty of low-down pulling power.

At the higher 60mph (961cm/h) motorway limit, with the engine pulling 1,900rpm in top, long gradients quickly call for 7th as the revs fall away.

• HILL CLIMBING

When driving over hilly roads the torque curve could well be imagined to have a pronounced tilt to the left, as the Hino shows little tenacity below 1,400rpm and is hardly inclined to lug down at all. This was particularly noticeable on the M6 over the long, grinding haul past Lancaster and on towards Shap summit where its speed dropped below 481cm/h and sixth and seventh gears were needed repeatedly as the gradient steepened.

These slow hill-climb times underline the Hino's shortcomings, particularly the long gaps between the ratios in the unforgiving Fuller gearbox. On the snaky Carter Bar climb with its 4.7% average gradient, the Hino took almost seven minutes to reach the English border summit: because of those widely spaced ratios it was necessary to hold it in fourth for long stretches.

The steep, 2.31cm Blackhill climb towards Consett proved the most demanding on our route; the Hino took eight minutes (the same time as the Scania P92M) and needed first gear (not crawler) on several occasions to make it to the top of the hill. reasonably light clutch pedal and quite acceptable gear lever loading. This is a blessing, because on steep hills the engine's lack of pulling power calls for some nimble skip-shifting to maintain momentum while dropping quickly through the gears.

Quite early on our test route, over the A68 at Redesdale, this proved our undoing when a missed gear brought the Hino to a halt. Thanks to its good gradability and a dry surface the combination was soon under way again — but had the road been wet or frosty, its lack of a cliff-lock might have proved embarrasing.

Hino is not likely to supply one as standard, but it does offer the Eaton Twin Splitter gearbox as an option at a premium of £1,500. The Twin Splitter's far quicker changing should improve the Hino's performance considerably while eradicating one of the cab's eyesores: the countershaft brake valve on the gear lever.

This valve, which is used to slow the RTX 11609B's gearshafts when engaging first or reverse gears, is attached to the gearlever rather crudely by a hose clip whose tongue sticks out just where an unwary driver could catch his hand on it.

Plastic air pipes are bound to the lever with adhesive tape, and with the addition of an ill-fitting dust cover the whole arrangement looks rather untidy.

On the standard 3.2m wheel base the Hino 38-tonner offers a healthy payload of over 25 tonnes, including the standard spare wheel and carrier frame. Its kerb weight could be reduced still further by fitting parabolic road springs in place of its hefty 10-leaf semi-elliptic packs. Although these combine with telescopic dampers and substantial anti-roll bars to give a fairly stable ride over most road surfaces, over the worst sections of our route the ride became slightly choppy, and this was exaggerated by an excessive amount of cab movement.

Heading down the B6278 towards Shottley Bridge, the reasonably-well-sprung driver's seat did nothing to alleviate the nodding and pitching of the cab or, for that matter, that of the passenger's seat.

• BRAKING

Compared with most European-built trucks lithos have unusually narrow brake linings, measuring 127mm at the front and 178mm at the rear.

Hino's earlier 32.5-tanner had 203mmwide linings on the back brakes. When its drive axle locked up on test in 1982, we criticised it for producing a potential jackknife situation.

With Hino's latest SH283KA 38-tonner, fresh from type approval, full pressure stops from 48 and 641crn/h had the unit pulling to the right, with the drive axle's offside wheel also locking up. Under normal driving conditions around our test route, sometimes on wet roads, the brakes behaved well, with a nice, progressive feel which was helped somewhat on long downhill run's by Hino's automatically-operated exhaust brake. This was only moderately effective, which is surprising because the engine revs faster than most.

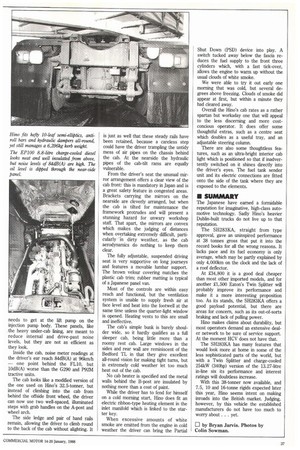

The exhaust brake works from an on/ off stalk switch on the steering column (which HCV suggests is left on all the time) via microswitches on the clutch and accelerator pedals. With the column switch on and both pedals released, the guillotine-type exhaust valve in the manifold is actuated automatically. needs to get at the lift pump on the injection pump body. These panels, like the heavy under-cab lining, are meant to reduce internal and drive-past noise levels, but they are not as efficient as they look.

Inside the cab, noise meter readings at the driver's ear reach 84dB(A) at 961cm/h — one point behind the FL10, but 10dB(A) worse than the G290 and P92M tractive units.

The cab looks like a modified version of the one used on Hino's 32.5-tonner, but instead of climbing into the cab from behind the offside front wheel, the driver can now use two well-spaced, illuminated steps with grab handles on the A-post and wheel arch.

The side ledge and pair of hand rails remain, allowing the driver to climb round to the back of the cab without alighting. It is just as well that these steady rails have been retained, because a careless step could have the driver trampling the untidy mess of air pipes on the chassis behind the cab. At the nearside the hydraulic pipes of the cab-tilt rams are equally vulnerable.

From the driver's seat the unusual mirror arrangement offers a clear view of the cab front: this is mandatory in Japan and is a great safety feature in congested areas. Brackets carrying the mirrors on the nearside are cleverly arranged, but when the cab is tilted for maintenance the framework protrudes and will present a stunning hazard for unwary workshop staff. That apart, the mirrors are convex which makes the judging of distances when overtaking extremely difficult, particularly In dirty weather, as the cab aerodynamics do nothing to keep them clear.

The fully adjustable, suspended driving seat is very supportive on long journeys and features a movable lumbar support. The brown velour covering matches the plastic cab trim; rubber matting is typical of a Japanese panel van.

Most of the controls are within easy reach and functional, but the ventilation system is unable to supply fresh air at face level and heat into the footwell at the same time unless the quarter-light window is opened. Heating vents to this are small and ineffective.

The cab's simple bunk is barely shoulder wide, so it hardly qualifies as a full sleeper cab, being little more than a roomy rest cab. Large windows in the sides and rear wall are reminiscent of the Bedford TL in that they give excellent all-round vision for making tight turns, but in extremely cold weather let too much heat out of the cab.

No cab heater is specified and the metal walls behind the B-post are insulated by nothing more than a coat of paint.

While the driver has to fend for himself on a cold morning start, Hino does fit an electric ribbon-type heating element in the inlet manifold which is linked to the starter key.

When excessive amounts of white smoke are emitted from the engine in cold weather the driver can bring the Partial Shut Down (PSD) device into play. A switch tucked away below the fascia reduces the fuel supply to the front three cylinders which, with a fast tick-over, allows the engine to warm up without the usual clouds of white smoke.

We were able to try it out early one morning that was cold, but several degrees above freezing. Clouds of smoke did appear at first, but within a minute they had cleared away.

Overall the Hino's cab rates as a rather spartan but workaday one that will appeal to the less discerning and more costconcious operator. It does offer some thoughtful extras, such as a centre seat which doubles as a useful tray, and an adjustable steering column.

There are also some thoughtless features, such as an ultra-bright interior cab light which is positioned so that if inadvertently switched on it shines directly into the driver's eyes. The fuel tank sender unit and its electric connections are fitted onto the side of the tank where they are exposed to the elements.

• SUMMARY

The Japanese have earned a formidable reputation for imaginative, high-class automotive technology. Sadly Hino's heavier Dublin-built trucks do not live up to that reputation.

The SH283KA, straight from type approval, gave an uninspired performance at 38 tonnes gross that put it into the record books for all the wrong reasons. It lacks pace and its fuel economy is only average, which may be partly explained by only 4,0001un on the clock and the lack of a roof deflector.

At £34,800 it is a good deal cheaper than most other imported models, and for another £1,500 Eaton's Twin Splitter will probably improve its performance and make it a more interesting proposition too. As its stands, the SH283KA offers a good payload potential, but there are areas for concern, such as its out-of-sorts braking and lack of pulling power.

Hino makes claims about durability, but most operators demand an extensive dealer network to be sure of service support_ At the moment HCV does not have that.

The SH283KA has many features that would look more at home in some of the less sophisticated parts of the world, but with a Twin Splitter and charge-cooled 254kW (340hp) version of the 13.27-litre in-line six its performance and interest ratings will doubtless increase.

With this 38-tonner now available, and 7.5, 10 and 16-tonne rigids expected later this year, Hino seems intent on making inroads into the British market. Judging, however, by this vehicle the established manufacturers do not have too much to worry about. . . yet.