Scania LBS110

Page 46

Page 47

Page 48

Page 49

Page 50

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

38-ton --gross a rtic

ONE of the more important models to be introduced by a European manufacturer in 1968 was the Scania 110 which Scania-Vabis of Sweden announced at the Amsterdam Show just about one year ago. Although based mechanically on its earlier 76 range with 275 bhp turbocharged diesel and 10-speed transmission, Scania-Vabis developed a completely new tilt cab for the 110 and at the same time made smaller changes including use of an improved change system for the splitter gearbox.

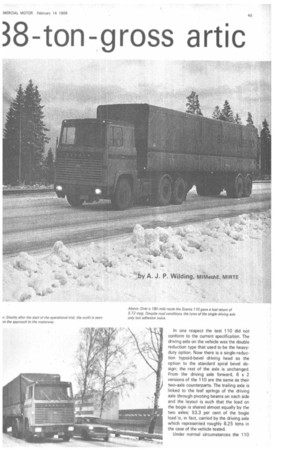

The 76 was tested just over a year ago (CM November 24 1967) and gave very good results running at a maximum gross weight of 32 tons. For this test of the new 110 which was again carried out in Sweden, a 6 x 2 tractive unit was provided and equally commendable figures were obtained at a 38 tons gross combination weight. An operational trial over a distance of almost 180 miles was the main part of the exercise and the 110 returned 5.72 mpg at an average speed of 34.8 mph. Snow and slush on the roads for most of the route made for a reduction in what would have been a normal average speed and also had an adverse effect on consumption. But one of the objects of this particular test was to assess the suitability of a single-drive six-wheeler for 38 ton gross operation. The design proved satisfactory for the conditions and adhesion was lost on two occasions only during the test.

There were problems in completing acceleration and brake tests but these were eventually carried out using a covered loading bay at the Scania-Vabis works. The brakes showed an adequate reserve of power and acceleration times were well up to the standards of much lighter outfits. The Scania 110 was a very comfortable and easy vehicle to drive. There was a relatively lively road performance and the engine was very quiet. The power steering was light and positive and the brakes were responsive which made for a feeling of confidence in driving the outfit.

The engine used in the LBS110 Super which is the full designation of the six-wheeler tested is an 11.0 litre diesel and the turbocharged version as in the test vehicle is the optional power unit producing 275 bhp net (DIN) at 2,200 rpm with maximum net torque (DIN) 780 lb.ft. at 1,500 rpm. Like the engine, the main section of the gearbox in the test machine was identical to that used in the 76 tested in 1967. The transmission alteration applies to the integral splitter section at the rear of the box and instead of a mechanical change linkage, the planetary gearing for engagement of direct or the 1.36 to 1 step-down ratio is controlled by an air-pressure system actuated electrically through a switch on the main-change lever.

The new design was found to be a big improvement over the old "two-stick" change and there was never a time when the splitter gearing did not change correctly; the secondary ratio is pre-selected with the switch and the change completed on depression of the clutch pedal. As is usual with synchromesh gearboxes on this class of machine the action of changing gear in the main part of the box was fairly heavy—as compared with most constant-mesh designs. But in general the synchromesh—on the upper four ratios—worked well even though it was possible to ''beat"

it with fast changes into second and third. continuee

In one respect the test 110 did not conform to the current specification. The driving axle on the vehicle was the double reduction type that used to be the heavyduty option. Now there is a single-reduction hypoid-bevel driving head as the option to the standard spiral bevel design; the rest of the axle is unchanged. From the driving axle forward, 6 x 2 versions of the 110 are the same as their two-axle counterparts. The trailing axle is finked to the leaf springs of the driving axle through pivoting beams on each side and the layout is such that the load on the bogie is shared almost equally by the two axles; 53.3 per cent of the bogie load is, in fact, carried by the driving axle which represented roughly 8.25 tons in the case of the vehicle tested_ Under normal circumstances the 110

6 x 2 would have been fitted with a-bogie lift system with which weight is transferred on to the driving axle and which in the unladen condition has the effect of raising the trailing axle off the ground. This would have had the effect of increasing the driving axle load to about 10 tons but the test vehicle was not equipped in this way as it had been designed for the German market. The brakes also were to a layout required in Germany. The same basic system will apply to all chassis with the front axle and rear bogie on separate circuits but whereas spring brakes were fitted at the driving axle only for parking purposes this type of actuator will be fitted at the front axle also on chassis sold in Britain.

It would appear essential to have at least two axles braked for parking to meet the British requirements-ability to hold the fully laden outfit on a 16 per cent gradient (1 in 6.25) 5.25) to the Code of Practice for dewhen in service and 19 per cent (1 in sign-and although road conditions did not allow a check to be made, the result of the dynamic handbrake test suggests that the spring brakes on the driving axle only would not hold the 38 ton outfit on a gradient of much more than 1 in 8.

For Britain also there will be a thirdline connection to the semi-trailer for secondary brake purposes and a trailer would have a second air circuit also. The ASJ-Fruehauf unit used for the tests had a very simple braking system with singlediaphragm actuators all round and an interesting feature of the design was that the axles used Scania-Vabis components such as hubs and brake units. This is common in Sweden where the operators specify axles on their semi-trailers of the same make and design as those used on their tractive units.

All testing with the Scania and its trailer was carried out in the fully laden condition with a payload of 23.28 tons which with two men in the cab brought the gross weight to just under the 38 ton mark. As already stated, one of the main reasons for doing the test-apart from getting performance and fuel consumption figures and generally assessing the design-was to see how a singledrive six-wheeler would cope with a 38 tons gross weight. In all the talks that are going on about a possible increase in the British maximum legal weight for artics there are suggestions that an uprating to 38 tons or more will be linked with a requirement for a 6 x 4 tractive unit for this weight. But if such a precedent of defining design requirements in the Regulations is taken, it will go completely against policies and practices in the rest of Europe where a single driving axle is generally considered adequate for gross weights of this order.

If double drive were needed one would expect tractive units operated in countries such as Sweden where snow must frequently bring conditions of low adhesion, to be of the double-drive type when gross weights of 30 tons or more are involved. But this is definitely not the case and it is only recently that the local manufacturers such as Scania-Vabis have offered tractive units with a double-drive rear bogie.

A common right

A common sight on Swedish roads is the 6 x 2 tractor operating at the local maximum gross weight of up to 40 tons gross combination weight. To obtain an idea of how such an outfit will operate on low adhesion surfaces I purposely timed this road test so that there would be a chance of getting some snow on the ground. The timing worked out just right with the first real snow of the Swedish winter falling during the test and even though this followed rain which made road conditions pretty treacherous, difficulties with adhesion occurred on two occasions only. And this was with a driving axle load of only just over 8 tons. If the bogie-lift-system had been fitted and 10 tons had been able to be applied, it is unlikely that adhesion would have been lost.

The first occasion that adhesion was lost was right at the start of the operational trial. About 100 yards from the Scania-Vabis offices in Sodertalje from where I started the test there is a slight at the junction with the road to E4 way. Unfortunately, we had to stop fairly deep slush and could not get again. Use of the differential lock not solve the problem but it was acessary to make a short run back the driving wheels to grip and they could be kept rolling through zard there was no more difficulty. ads in Sodertalje and the surface of arside lane of the motorway were y clear of snow and it was not until it towards Nykopping that there ny amount of snow on the road. :here it was only in patches and were not continuous stretches of or slush-covered roads until we Bettna. From this point the roads • ed down quite a lot—to about ride--and there were more bends : whereas only one or two changes e low splitter ratio had been made the town of Bettna there were it changes into fifth-low after This was entirely due to the of the road and the weather con. The gradients were about the is on the earlier part of the run and notable that in spite of the 38 tons weight the Scania romped over he worst hills—where gradients up to about 1 in 12—with no down from top-low. On the more difficult stretch to Flen it was frequently necessary to come almost to a stop to allow oncoming vehicles to pass with safety. When just before Flen we left the slush—the roads afterwards were just wet—and the road widened to about 2511. After Flen the road was rough in places but good suspension on the Scania ironed out the bumps quite effectively and there was no pitching. Up to Strangnas and on to Enkopping the road flattened out and was of reasonable width with about 1in. of slush and snow covering most of this section.

Shortly before the lunch stop at Enkopping—the turning round point—it was discovered that a fault had developed with the flashing indicators. Some time was spent trying to cure the trouble but without success. With darkness starting to come down—it was about 2.30 was decided that no more time could be afforded on finding the electrical fault so the return run was started.

It was discovered on the return to Sodertalje that water in the electrical coupling to the trailer was the cause of the fault which resulted in all the flasher units on the nearside of the vehicle being permanently "on". This caused concern when driving in the dark; concern that vehicles behind would think that a signal that it was safe to overtake was being given. This was a distraction and called for extra concentration.

With snow falling heavily at this time and the lights not able to pick up the centre marking and edge of the road, driving was difficult. It was fortunate that most of the 30 miles from Strangnas to Sodertalje was on fairly wide and reasonably flat roads but a lot of traffic and narrower roads near Sodertalje called for delicate control of the outfit.

The many good points of the Scania were a great advantage on this stretch, particularly the light and positive steering and the responsive brakes but frequent changes in speed and sudden braking must have had an effect on the fuel consumption as well as the average speed returned.

In spite of the extra mental effort needed for the conditions the 178.8 mile journey had not been excessively tiring. The mirror equipment on the 110 was found to be very good indeed. Some road dirt got on the mirrors making cleaning necessary every 30 miles or so but this is a common occurrence on modern flatfront vehicles. In better road conditions I would expect the 110 tested to give a fuel consumption of something over 6 mpg at 38 tons gross and over the sort of terrain encountered. The 5.72 mpg actually obtained is, in itself, not a bad figure for a 38 ton gross outfit.

On the day after the main run, brakes and acceleration performance were checked. Because all the roads in the area by this time had a layer of snow it was necessary to use a covered loading bay at the Scania-Vabis factory. There was some dampness on the surface caused by vehicles using the area bringing snow in on their tyres and so the figures of 31.4ft for a maximum pressure stop from 20 mph and 67.3ft from 30 mph can be considered to be very good.

Acceleration

Acceleration tests were more difficult to complete and it was not possible to get up to 40 mph with safety in the restricted area available but those times that I was able to obtain confirmed the liveliness of the outfit and the figures compare very well with results from previous tests of 30 and 32 ton gross artics. The standard of cab and interior fittings on the Scania-Vabis 76 model was very high and the 110 cab is even better. It seems that no expense is spared to give the driver a most congenial atmosphere in which to work and the trim follows the practice used on luxury cars. The driving position is fairly high and this helps with forward visibility and also means that there is little intrusion of the engine cover into the cab. These advantages have to be paid for by a two-step climb to get into the cab but there are well placed grab handles on both sides of the door openings. The heating system supplied as standard in the 110 has an extremely high output and even though the day on which I carried out the test was cold and damp the heat control was close to the minimum setting and there was still an even and comfortable temperature throughout the cab.

There is no doubt in my mind that the 110 makes a worthy successor to the previous 76 design. The cab improvements add gilt to the gingerbread and with the better engine accessibility through the use of a tilt cab make what must be a most acceptable chassis.