AMERICA AND THE CRUDE-OIL ENGINE.

Page 19

Page 20

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

Two Power Units Suitable for Commercial Vehicle Propulsion, and Claimed to be Superior to Engines of the semi-Diesel Type. By Henry Sturmey.

I READ with much interest the article in a recent issue of The Commercial Motor, headed "An Epoch-making Power Unit," dealing with the Peugeot development, but, interesting as this engine is, it appears to me that what has already been done in America is a very much greater advance, as, instead of a semi-Diesel engine, America has produced what I would be inclined to call a 'Super-Diesel; which, working on the fourstroke principle, is very much more analogous to the ordinary petrol engine than is the Peugeot construction.

I am referring to an engine which has been produced, so far back as 1918, by the Mid-West Engine Co., and which not only burns crude oil or any other hydro:carbon except petroleum spirit, but does it without the need for any special compressor or fuel-injection-under-pressure device, and also requires no electric or other th-eans for igniting the first or any other charges. The injection of the fuel —which is not injected with the oil—is done at atmospheric pressure, although the compression used in the engine is 50 per cent. greater than that mentioned as used in the Peugeot, the pressure employed being 400 lb. to 450 lb. per sq. in. Yet the weight of the engine is less than 30 per cent. greater than the weight of a corresponding engine of the ordinary commercial car engine type, and I have

no doubt that this can be substantially reduced with further experiment.

.The unit I refer to is a four-cylinder engine, built as stated, by the MidWest Engine Co. four years ago, and it was .illustrated and described in full by the engineer to that Company in a paper read before the American Society of Automotive Engineers about 2i years ago. As this very much interested me, I got in touch with the Mid-West Co., and learnt a good deal about the engine at that time, but nothing was said about it here, as I was waiting for it to be placed on the market commercially. Owing to the abnormal conditions which, in America as with us, followed the war, the company found itself so fully engaged on the production of its regular engines that it had no time further to follow up the matter.

I may add, however, that this engine, if I recollect rightly, gave revs, up to 1,750 per minute, so that itwould appear to have reached a point of quite practical utility so far as motor lorry and tractor engines are concerned. It seemed to me, at the time I read of it, that, for commercial work at any rate, it was a type which, when perfected, should carry all before it, because of the character of the fuel used and its high fuel efficiency—stated to be .5 lb. per blip. hour—and the abolition of all ex

ternal fuel devices or ignition equipment. So far as the system itself is concerned, this engine is only a development of one which, for industrial and marine purposes, has already been proved in service over a period of five or six years, and something like a dozen firms in the States, as well as one or Awn in Canada, are to-day making industrial and marine

engines under the patents. Most of these firms are making single-cylinder horizontal hopper-cooled farm engines of frem 1i h.p. to 9 h.p., but others are working on larger lines. Thus, the Boos Engine Co. are making single-cylinder horizontal industrial engines up to close on 100 b.h.p., whilst the Dodge Engine Co., who a couple of years ago took over the business of the Durnoil Engine Co., the first licensees, are making both industrial and marine engines on the standardised unit principle, using a 121 h.p. engine unit, which is supplied in one, two, three, four and six-cylinder models, giving corresponding aggregates of engine power, and, so far as my information goes, these engines are all of • them highly successful.

They are all made under-licences from the Hvid Syndicate, who are the owners of the patents, the patentee being a Swedish-American, and most of the farm engines made by the different firms are practically duplicates of each other. The Mid-West, Engine Co., as before mentioned, has developed the unit as a motorcar engine. Unfortunately, I have mislaid the papers, so that I am unable to give an illustration of the actual car engine, hut I may say that in general appearance there is very little observable difference from an ordinary petrol engine, except that it is cleaner in design, owing to the absence of carburetter and ignition equipment. I show, however, the design of one of the Dodge cylinder heads, which will fully explain the principle and the constructional detail adopted, the difference mainly being only with regard to size.

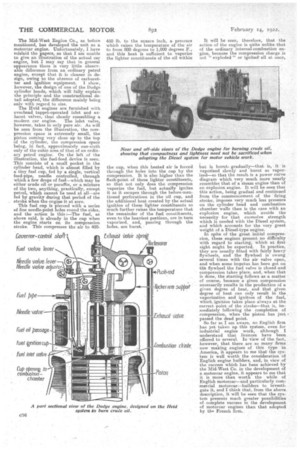

The Hvid engines are furnished with overhead tappet-operated inlet and exhaust valves, thus closely resembling a

modern car engine. The inlet valve, however, takes in only pure air. As will be seen from the illustration, the compression space is extremely small, the piston wining very close up to the top of the cylinder, the compression space being, in fact, approximately one-sixth only of the cubic area of that of an ordinary petrol engine. On the left of the illustration, the fuel-feed device is seen. This consists of a small pocket in the cylinder head, which is almost filled by a tiny fuel cup, fed by a single, vertical feed-pipe, needle controlled, through which a few drops of fuel—which may he either crude oil or paraffin, or a mixture of the two, anything, practically, except petrol, which cannot be used at all—are fed by gravity during that period of the stroke when the engine if at zero.

This fuel cup is pierced with a series dime needle-point holes round the sides, and the action is this :—The fuel, as above said, is already in the cup when the engine starts on its compression stroke. This compresses the air to 400 450 lb. to the square inch, a pressure which raises the temperature of the air to from 800 degrees to 1,000 degrees F., and this heat is sufficient to vaporize the lighter constituents of the oil within the cup, when this heated air is forced through the holes into the cup by the compression. It is also higher than the flash-point of these lighter constituents, so that not only does the compression vaporize the fuel, but actually ignites it as it escapes through the before-mentioned perforations in the oil cup, and the additional heat created by the actual ignition of these lighter constituents so much further raises the temperature that the remainder of the fuel constituents, even to the heaviest portions, are in turn vaporized, and, passing through the holes, are burnt. It will be seen, therefore, that the action of the engine is quite unlike that of the ordinary internal-combustion engine, because the compression charge is not " exploded " or ignitedall at once, but is burnt, gradually—that is, it is vaporized slowly and burnt as vaporized—so that the result. is a power curve diagram which very much more nearly resembles that of a steam engine than of an explosion engine. It will be seen that this action, being gradual and continued from the commencement of the firing stroke, imposes very much less pressure on the cylinder head and combustion chamber walls than is the case with an explosion engine, which avoids the necessity for that excessive strength which is needed with the Diesel system, and which accounts for the very great weight of a Diesel-type engine. In spite of the great initial compression, these engines present no difficulty with regard to starting, which at first sight might be expected. In practice, they are usually fitted with fairly heavy flywheels, and the flywheel is swung several times with the air valve open, and when some impetus has been got on th'e flywheel the fuel valve is elosed,and compression takes place, and, when that is done, the starting follows as a matter of course, because a given compression necessarily results in the production of a given degree of heat, and that given degree of heat can only result in the vaporization and ignition of the fuel, which.ignition takes place always at the correct point of the stroke—that is, immediately following the completion of compression, when the piston has just passed the dead point.

So far as I am aware, no English firm has yet taken up this system, even for industrial engine work, although I understand that licences have been offered to several_ In view of the fact; however, that there are so many firms now making engines of this type in America, it appears to me that the system is well worth the consideration of English engine builders, and, in view of the success which has been achieved by the Mid-West Co. in the development of a motorcar engine, it appears to me that it is more than worth the while of English motorcar—and particularly.comL inercial motorcar—builders to investigate it, and I think that, from the above description' it will be seen that the system presents much greater possibilities of complete success in the development of motorcar engines than that adopted by the French firm.