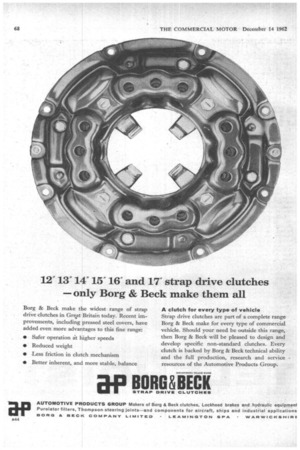

ap BORG&BECK

Page 70

Page 71

Page 72

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

STRAP DRIVE CLUTCHES AUTOMOTIVE PRODUCTS GROUP Makers of Borg & Beck clutches, Lockheed brakes and hydraulic equipment Purolator filters, Thompson steering joints—and components for aircraft, ships and industrial applications BORG & BECK COMPANY LIMITED • LEAMINGTON SPA • WARWICKSHIRE

Using the large fuel-test tank provided, a fuelconsumption run was conducted first, the prevalence of ice and snow making it impossible to consider doing brake tests early in the morning, but there being hope of a thaw taking place. The test route was 32.2 miles long and started from the Foden works at Elworth, thence through Middlewich, Northwich, Mere, Knutsford, Holmes Chapel and back to the Foden works. The first half of this route is reasonably level and little traffic was encountered upon it so it was easy to maintain a cruising speed of about 33 m.p.h. The second part of the course, however, is more hilly and traffic congested, which made it necessary to use the intermediate box ratios on 'several occasions.

Nevertheless, the course was completed at an average speed of 29 m.p.h.; and an accurate check of the fuel used showed the consumption rate to have been 11.9 m.p.g. This is an exceptionally good figure for a vehicle running at virtually 20 tons gross and, combined with the average speed, shows that this tiny Foden engine can be acclaimed not only for its fuel economy but also for its power.

There was not time to take unladen fuel-consumption figures, but these can be expected to be at least 60 per cent better than those obtained when carrying a full payload.

Similarly, in the single day at my disposal it was not possible to take full-throttle motorway figures because of the distance involved to get to the nearest stretch of motor way. This problem should be overcome with future Foden tests, however, because the Lancashire motorway passes within a couple of miles of Foden's front door, and this is scheduled to be in operation within 12 months. Figures taken under motorway conditions by the Foden experi mental department indicate that the fuel consumption under full-throttle conditions can be about 1 m.p.g. better than those Obtained during my normal-speed test.

Following the fuel run, acceleration tests were carried out. Entirely satisfactory times were obtained, both through the gears and in direct drive—appreciably better, in fact, than those recorded in 1958 with the eight-wheeler, thereby proving further that the low-speed torque charac teristics of the current Mk. VI engine are vastly superior to those of the Mk. H unit. Furthermore, this torque is delivered smoothly, for when conducting the direct-drive tests there was no apparent engine or transmission roughness when pulling away from 8 m.p.h., which is equivalent to an engine speed of about 500 r.p.m.

As luck would have it, road conditions improved towards the middle of the day and it was possible to find a stretch of dry, level road on which brake tests could be carried out. Although the figures obtained from the two test speeds are reasonably adequate, I was rather disappointed in the retardation performance generally, the braking specification having led me to expect that the six-wheeler would come to rest in no more than 65 ft. from 30 m.p.h. Obviously there was some time lag in the system. On the credit side, however, I must say that bogie-wheel' locking and hopping was not evident to any marked degree, probably because of the geometry given by the underslung springs. Slight locking of the driving wheels was observed during some of the tests, but for the most part these wheels just marked the road heavily. Stability when braking was good and nose diving not particularly pronounced.

Although a dry piece of road had been found for these tests, my hick ran out when it came to the hill-climb, the scene of which was that notorious Cheshire hill, Mow Cop. This slope has an average gradient of 1 in 9 and is 0.85 mile long, the steepest section at the very top being 1 in 3.75. The ambient temperature was 2°C. (35.6°F.) and the engine-coolant temperature before setting off up the hill was 68°C. (154.4°F.). The road was covered with partially frozen snow which gave the appearance of reducing the chances of making a successful ascent, though there were fairly wide ruts in the snow left by other traffic, so with fingers crossed the climb was started.

All went well for the first 2 minutes 45 seconds, but just after, a change had been made from bottom-direct to second-low the driving wheels started to spin and the vehicle had to be gently eased down to a less slippery part of the road. The gradient at this point was 1 in 5, and the handbrake held the Foden safely whilst the driver and I spread grit over the slippery part of the hill immediately ahead. This done, a restart was made in second-low and steady progress—partly in that ratio and partly in bottomdirect—was made to the foot of the 14n-3.75 section, the road speed remaining fairly constant at about 5 m.p.h.

The steep section was reached 5 minutes 45 seconds after the restart, but' it proved quite impossible to get enough traction to enable the final section to be climbed, though I feel sure this would not have been the case had our vehicle had a double-drive bogie.. Because of the high engine speed during the climb, the coolant temperature dropped to 65°C. (149°F.).

It would have been suicidal to have attempted my usual brake-fade test down Mow Cop that day, this being to coast the vehicle down the hill in neutral using the footbrake to hold the speed down to 20 m.p.h.: it was nerve-racking enough as it was having to feel our way down the hill in bottom-low! However, the brake-lining area is large, and the drums arc heavily ribbed to give maximum heat dissipation, so fade should not be a particular problem.

Engine Pulls Well

Safely off Mow Cop, the six-wheeler was driven to Radnor Hill, the maximum gradient of which is 1 in 7.5, for stop and restart tests. Facing on the hill, the handbrake held the vehicle with ease, following which a very good restart was made in bottom-direct, to the surprise of both myself and the Foden driver. While pulling away the engine was turning at a mere 700 r.p.m., and this speed was held for the best part of a minute until the gradient slackened oft and the engine revs. rose. Facing down the hill, the handbrake again proved its worth, but a reversedirect restart failed (this ratio is 5.41 to 1 compared with 6.18 to 1 for bottom-direct). Reverse-low was used for this restart, therefore, with ample power in hand.

Neither during these restart tests nor when on Mow Cop was there any sign of exhaust smoking, showing combustion to be complete.

The remaining checks were concerned with forward visibility, which was adequate, and the turning and swept circles, which were on the large side for a vehicle with an overall length of little more than 28 ft. This question of steering lock is to be tackled on future chassis, which will have the steering box farther forward so that the offside wheel cannot foul the steering drop arm.

My reactions to this Foden six-wheeler were, generally, more than merely favourable, my criticisms being limited to the braking-system delay, the poor steering lock, the tendency for the front suspension to be harsh at times, and certain cab details—particularly the use of balanced-drop as opposed to wind-down windows in the doors. The vehicle handled very well indeed, the steering being light and direct (although prone to road reaction over bad surfaces), gear changing being no trouble at all once I had got accustomed to the clutch stop, the brakes being pro gressive, and engine noise at cruising speeds quite moderate, although—as might be expected—the level of noise rises appreciably to a high-pitched whine when accelerating hard through the gears or when hill-climbing in the lower ratios. Time limitations made it impossible for me to carry out maintenance tests on the six-wheeler, but these should have produced similar results to those recorded in 1958 in connection with the eight-wheeler. Among the differences between these two vehicles, mention should be made of the more accessible location of the air cleaner—though its position restricts the passenger's leg room. Generally, had found the eight-wheeler reasonably easy to service. Compared with a mass-production medium-capacity four-wheeler with a third-axle conversion, the Foden KE.4/20 is not cheap, its chassis-cab price being £3,980 in the form tested, but for this money the purchaser gets an extremely robust, well-designed vehicle with a long life potential, an endless capacity for hard work and outstanding overall economy.

A POWERFUL defensive weapon has ri been put into the hands of hauliers by the clause in the new Road Traffic Act which says that it shall be deemed to be a defence if an employer, in drivers' records cases, can prove that he has used all due diligence to ensure that the law was complied with. This came into effect on November 1, but no instances seem yet to have been recorded of what constitutes "proof of due diligence."

The nearest "instance" came recently when the Leeds Stipendiary Magistrate said that he thought, regardless of other instructions, that if some indication in writing was given to each driver, on his log sheet, of the importance of the driver complying with the law, "due tieligence " could be argued on the employer's behalf with some certainty.

As long ago as 1935 the Goods Vehicles (Keeping of Records) Regulations fastened firmly upon them the obligation to cause current records to be kept. Failure, however inadvertent or unwitting, could spell conviction, penalty, and more important, possible suspension or revocation of their carriers' licences.

During the course of 1962, no fewer than four important cases dealing with this subject have been argued in the courts. In one, Mr. Richard Vick, defending a Wapping transport company, is reported to have said: "When an employee goes off on a frolic of his own, it does not mean that the employer is obliged to cause a record to be kept of it. The driving he does must be in the course of his employment."

Davis Appeal In another, fines and costs amounting to over £330 were inflicted on Davis Brothers (Haulage), Ltd., in the Tower Bridge magistrates' court, after two of the firm's drivers, who were themselves fined, had said they took the vehicles home without the specific permission of the firm. An appeal by the company at the London Sessions in May was successful in only four out of 12 cases tested. In a third case, this time against a haulier at Gateshead, the " frolic " defence was unsuccessfully pleaded.

But a fourth case, which was taken on appeal to the Divisional Court, is the most interesting. Jacks Motors, Ltd., of Blackburn, Lanes, were convicted and fined by BlaCkburn magistrates for failing to cause a correct driver's record to be kept. The driver, coming from the South, made an entry in his record book that he spent the night at Rugeley, Staffs, but at 7.24 p.m. that day his vehicle was seen at Worsley, Lanes, which is on the way to Bolton, where he lived. On appeal by Jacks against their conviction the question arose:— Was the employee working in an Bel6 irregular and unauthorized manner or acting wholly outside the scope of his employment?

In the course of his judgment, the Lord Chief Justice (presiding) said: " For my part 1 am satisfied, although I am told that the matter is going to be challenged in' the future, that the obligations laid down by section 186(1) of the Transport Act are absolute and that lack of know ledge . . does not affect the issue at all." He thought, however, that if and in so far as a driver was out purely on a frolic of his own, there was no obligation on the employers to ensure that journeys which were not for them were recorded in the record. The record that had to be kept was a record of the times at which the driver started and finished work; and "work," he thought, must mean work for the employer.

Magistrates Stand Fast •

In thinking that the absolute obligation extended to journeys outside the scope of employment, the justices were wrong. The question remained whether the driver, after Rugeley, could be said to be working within the scope of his employment or not. The case was accordingly sent back to the magistrates to determine that issue.. The magistrates reheard the case on June 15 and although counsel for the defence contended that the driver, having gone to Bolton entirely for his own purposes, was clearly not on his masters' business, the bench found as a fact that from Rugeley northwards, a considerable part of the journey was in the scope of the driver's employment, and reaffirmed their decision to convict the employers.

It would be short-sighted, however, to assume that this appeal has served no purpose. There have been arguments in the past about that clause in the Keeping of Records Regulations which reads: • "The holder of a licence shall not be required to keep the records prescribed by these Regulations in respect of the driving by him of any vehicle authorized under that licence on journeys which are in no way connected with any trade or business carried on by him."

Those words can clearly be said to mean that if the holder of a carrier's licence wants to use his vehicle to take him on some pleasure trip unconnected with his trade or, business, he need not make a statutory record of that journey. But what is the position of the holder of the licence if he lends the vehicle to his driver in order that the borrower may go on a pleasure 'trip? Must the journey be included in the driver's statutory record? Would the lender be guilty of an offence if it were not? Note

the words "in respect of the driving by him."

One school of thought believed that it followed from those words that if the driving is done 'by someone other than the licence-holder, a statutory record has to be kept by that other person. On the other hand it has been argued that such an inference is unwarranted in the absence of plain, positive words to that effect.

Does the parent Act, the Road Traffic Act, 1960, give any clue? Section 73(1) opens: "With a view to protecting the public against the risks in cases where the drivers of motor vehicles are suffering from excessive fatigue, it is hereby enacted that it shall not be lawful in the c'ase of . . . a motor vehicle constructed to carry goods other than the effects of passengers for a person to drive or cause or permit a person employed by him or subject to his orders to drive . . . more than the maximum number of hours specified in the section."

There is no distinction drawn here between driving for trade or business purposes and pleasure purposes. The licensee mbst not "cause or permit a person employed by him " to drive for more than the stipulated number of • hours. And records, of course, are the instruments for checking.

Limited Obligation The views of the Lord Chief Justice in the Jacks Motors case have at least cleared the fog to some extent. Quite evidently he thought that there was no obligation on the employers to ensure 'that journeys which were not for them were included in the record. By saying that the justices were wrong in thinking that an employer's absolute obligation extended to journeys outside the scope of the driver's employment, he brought the question back to what constitutes employment.

Take two common types of case. In the first, a driver takes a vehicle on a journey unconnected with the trade or business of his employer. It could be either a frolic or a funeral, and be carried out with or without sanction.

In the second and more frequent sort of case, a driver spends the night at some unauthorized and unrecorded place. He may do so for the purpose of claiming a subsistence payment, 'or for a wide variety of other reasons.

The Jacks Motors appeal cleared the air in the first, but left doubt about the second set of circumstances. It will depend on the precise and detailed facts of the particular case whether the employer can show in future either that the obligation to cause proper records to,, be kept does pot arise or that he has exercised due diligence about them. '