Five Tons per Cylinder

Page 66

Page 67

Page 68

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

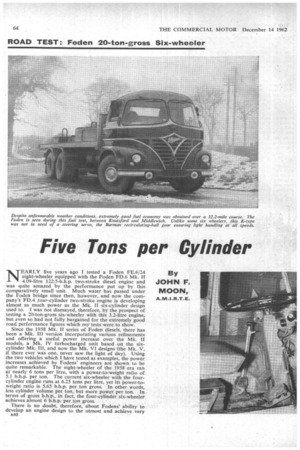

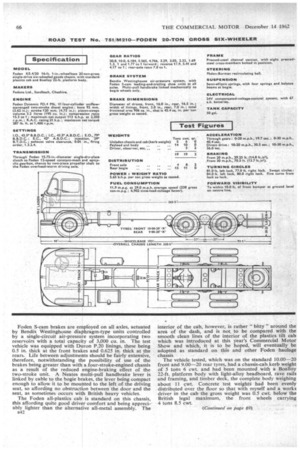

NEARLY five years ago I tested a Foden FE.6/24 eight-wheeler equipped with the Foden FD.6 Mk. II 4.09-litre 122.5-b.h.p. two-stroke diesel engine and was quite amazed by the performance put up by this comparatively small unit. Much water has passed under the Foden bridge since then, however, and now the company's FD.4 four-cylinder two-stroke engine is developing almost as much power as the Mk. II six-cylinder design used to. I was not dismayed, therefore, by the prospect of testing a 20-ton-gross six-wheeler with this 3.2-litre engine, but even so had not fully bargained for the extremely good road performance figures which my tests were to show.

Since the 1958 Mk. II series of Foden diesels, there has been a Mk. HI version incorporating various refinements and offering a useful power increase over the Mk. II models, a Mk. IV turbocharged unit based on the sixcylinder Mk. III, and now the Mk. VI designs (the Mk. V, if there ever was one, never saw the light of day). Using the two vehicles which I have tested as examples, the power increases achieved by Fodens' engineers are shown to be quite remarkable. The eight-wheeler of the 1958 era ran at nearly 6 tons per litre, with a power-to-weight ratio of 5.1 b.h.p. per ton. The current six-wheeler with the fourcylinder engine runs at 6.25 tons per litre, yet its power-toweight ratio is 5.65 b.h.p. per ton gross. In other words, less cylinder volume per ton, but more power per ton. In terms of gross b.h.p., in fact, the four-cylinder six-wheeler achieves almost 6 b.h.p.• per ton gross. •

There is no doubt, therefore, about Fodens' ability to develop an engine design to the utmost and achieve very B40 high unit power-to-weight ratios, the four-cylinder engine's ratio being 9.3 lb. per net b.h.p. and its power-to-volume ratio being 35.3 net b.h.n. per litre. A remarkable little engine all told, which offers a number of positive advantages over bulkier and heavier four-stroke engines of similar power output, notably good fuel economy and reduced chassis weight.

Taking the four-cylinder engine, it is interesting to look at the differences between the 1958 Mk. II and the 1962 Mk. VI units. To begin with, b.h.p. has been increased by 37 per cent, whilst maximum torque has gone LID by nearly 26 per cent, despite which the cylinder capacity has been increased by only 17.4 per cent, this having been accomplished by enlarging the bore from 85 mm. to 92 mm. Crankshaft speed is only 250 r.p.m. higher, so it is obvious that the extra power is derived principally from changed combustion and breathing arrangements to augment the increased cubic capacity. The b.m.e.p. has gone up, of course—from 100 to 108 p.s.i.—and the higher loadings are accommodated by thin-shell reticular aluminium-tin main and big-end bearings.

So far as the six-wheeler which I recently tested is concerned, the standard engine is the FD.6 six-cylinder two-stroke, the output of which is 50 per cent up on that of the optional, four-cylinder unit. Further engine options include the Gardner 5LW, 6LW and 6LX. With either of the Foden engines a five-speed crawler-low gearbox is standard, with the option of the Foden 12-speed transmission, this consisting of a four-speed main box integral with which is an epicyclic auxiliary section giving overdrive and underdrive ranges to the four main ratios. With the standard 7.0-to-I axle, the 12-speed box gives a theoretical gradient maximum ability of I in 2.34 in bottom-low, and a theoretical maximum speed of 47.5 m.p.h. in top-high. It will be recalled that, until recently, the Foden 12-speed

gearboxwas controlled by two separate gear levers, the smaller lever actuating the auxiliary section affordingpre-selection. This secondary floor-mounted lever has been replaced by an electric switch mounted on the righthand side of the steering column housing, making for finger-tip selection of the auxiliary ratios and so encouraging maximum use to be made of the available gear ratios. Even with the comparatively small four-cylinder engine the life of the driver does not consist of one endless succession of split gear changes, however, it being necessary under normal conditions only to use the direct and overdrive ranges of the auxiliary box in conjunction with the four main-gearbox ratios, and the ease of control is such that the method of driving is akin to that employed when handling a vehicle with a two-speed axle.

Indeed, I would say that less gear changing was required with this four-cylinder six-wheeler than with the sixcylinder eight-wheeler tested early in 1958, and this is undoubtedly due to the greatly improved low-speed torque characteristics of the Mk. VI engine, the torque curve being commendably flat throughout the normal speed range.

A single-drive bogie, with 8.75-in.-centre overhead-worm gear, is standard, with the option of double-drive bogies with 8or 8.75-in. worms. Normally 6.25-to-1 gearing is employed, but with the four-cylinder engine the lower 7.0-to-I axle is fitted. In all cases the bogie suspension consists of four 3.5-in.-wide semi-elliptic springs. These are underslung, and are linked via a conventional layout of central balance beams and swinging shackles. Each spring has a rating of 3.5 tons, although 4-ton springs are optional.

The standard front axle is a 5-ton assembly, whilst the front springs are 3.5 in. wide and are each rated to carry 2 tons 3 cwt. A 6-ton axle, with wider brakes, can be specified, but it is unlikely that this should be necessary under normal haulage conditions in Britain as the frontaxle loading is rarely likely to exceed 5 tons. Burman recirculating-ball steering gear is incorporated in the Foden steering column, the standard ratio being 29 to 1 irrespective of whether the steering is assisted or not, a hydraulic servo being available although not really necessary.

There are two basic versions of the standard Foden six-wheeler, these having wheelbases of 16 ft. 1 in and 17 ft. 6 in., with 12.in. by 4-in. by 0.25-in, chassis-frame side members. Tipper chassis, of which there are four, with wheelbases ranging from 11 ft. 3.125 in. to 15 ft. 1.75 in., have 0.3125-in.-thick main members, the two longer chassis being available with frames of this section also. In view of the relatively low weight of the chassis, the size of the standard frame is praiseworthy, and trouble in this quarter should rarely occur, the more so since there are eight large cross-members bolted in place.

Foden S-cam brakes are employed on all axles, actuated by Bendix Westinghouse diaphragm-type units controlled by a single-circuit air-pressure system incorporating two reservoirs with a total capacity of 3,000 Cu. in. The test vehicle was equipped with Duran P.20 linings, these being 0.5 in. thick at the front brakes and 0.625 in. thick at the rears. Life between adjustments should be fairly extensive, therefore, notwithstanding the possibility of use of the brakes being greater than with a four-stroke-engined chassis as a result of the reduced engine-braking effect of the two-stroke unit. A Neates multi-pull handbrake lever is linked by cable to the bogie brakes, the lever being compact enough to allow it to be mounted to the left of the driving seat, so affording no obstruction between the door and the seat, as sometimes occurs with British heavy vehicles.

The Foden all-plastics cab is standard on this chassis, this affording quite good driver comfort and being appreciably lighter than the alternative all-metal assembly. The B42 interior of the cab, however, is rather " bitty " around the area of the dash, and is not to be compared with the smooth clean lines of the interior of the plastics tilt cab which was introduced at this year's Commercial Motor Show and which, it is to be hoped, will eventually be adopted as standard on this and other Foden haulage chassis The vehicle tested, which was on the standard 10.00-20 front and 9.00-20 rear tyres, had a chassis-cab kerb weight of 5 tons 6 cwt. and had been mounted with a Boalloy 22-ft. platform body with light-alloy headboard, rave rails and framing, and timber deck, the complete body weighing about 11 cwt. Concrete test weights had been evenly distributed over the floor so that with myself and a works driver in the cab the gross weight was 0.5 cwt. below the British legal maximum, the front wheels carrying 4 tons 8.5 cwt.

(Continued on page 69)