BRITAIN'S TRIUMPH with the OIL ENGINE R AMER less than five

Page 92

Page 93

Page 94

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

,years ago the writer inspected the first oil-engined bus. for public service in this country, and took the wheel for a time in London traffic. At that tithe, the number of oil-engined chassis of all types in service on our roads could be counted on

the fingers of two hands. .

To-day the number of oilers registered in England, Scotland and Wales is little below 7,000. Surely that may, without exaggeration, be termed a triumph. This remarkable growth makes it all the more interesting to recollect the scepticism which was aroused by our enthusiasm in the " early " days of the oiler. Even those with no financial axe to grind heaped scorn upon the idea of "a scaleddown version of a stationary or marine propulsion engine" ever becoming popular for road vehicles.

Furthermore, this rapid progress has not been confined to the home market. In nearly fifty different countries of the world oil engines are in daily duty on the roads. A good proportion of these is British in origin. At first the German designs were almost alone in the overseas markets c38 by reason of the early experimental work carried out; most of the engines were of the pre-combustion type. British production models rapidly gained favour on account of their generally lower rates of fuel consumption. To-day the greater proportion of heavier chassis exported from our shores has compression-ignition power units. Our chief competitor is Germany, but, at the moment, there is a retarding influence in that country, because political efforts are being made to encourage home-produced spark-ignition fuels in preference to the use of import& oil fuels.

America, largely by reason of the existence of a very cheap petrol, has „come late into the field ; actually a fair number of British oil engines is in use in that "home of the motor trade." Most of the engine makes there are proprietary, but in this country and in Germany oil power units made by chassis builders and engine specialists find equal favour. In many other countries on the Continent and America British designs are manufactured under

licence—another triumph.

It is interesting to consider the present trend in sales in the home market. In the goods-vehicle section new registrations of machines weighing over 2i tons unladen show about two oilers for every petrol chassis. In the lighter categories, too, the progress of the compressionignition unit is beginning to be felt.: about 20 of them are now licensed per month. At present the percentage is small, but a year ago there was only an occasional one of a more or less experimental type.

Passenger-carrying chassis of 26-seats capacity and over at present sell in approximately equal proportion, as between oil and petrol, but several impending and recently placed orders will turn the scale in numerical favour of the former. Three recent orders for the London Passenger Transport Board alone total 274 oil-fuel buses, whilst Birmingham Corporation has placed two orders for 100 each, Obviously such commercial progress would not have been possible without a stage of technical development having been reached that ensured really satisfactory operation. Oil engines have had to satisfy users whose needs had previously wholly been met by petrol engines with some 30 years' "breeding" behind them.

In the past five years—which is the practical limit of the oil-engine period—many combustion systems have come to light; some of them have faded away again. One fact, however, • is outstanding. What we may term the " pure " type of ante-chamber has almost completely passed out of favour, leaving the field to direct injection, separate combustion chamber and air-cell types.

Big-end bearings of the latest types, having steel back lags and lead-bronze or cadmium-alloy wearing surfaces, or duralumin running on hardened journals, now run for 60,000 miles or so without even being inspected.

As an indication of the durability of the modern oil engine, we may quote an extract from the recent report of the Traffic Commissioners for the Northern Scotland Area, which is as follows:— " The life of many of these engines between successive overhauls has been greatly in excess of that of petrol engines of the same size fitted to the same make and type of vehicle; for example, a particular engine fitted to a doubledeck vehicle, ran for 150,000 miles, and when dismantled it was found that no attention was necessary to the crank shaft bearings, and that only new liners and pistons were required."

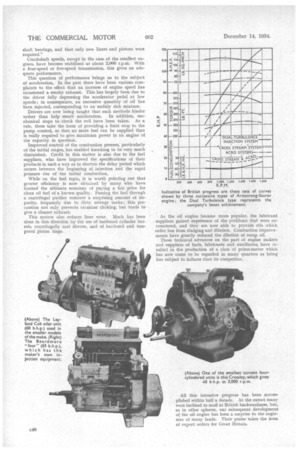

Crankshaft speeds, except in the case of the smallest engines, have become stabilized at about 2,000 r.p.m. With a four-speed or five-speed transmission, this gives an adequate performance.

This question of performance brings us to the subject of acceleration. In the past there have been various complaints to the effect that an increase of engine speed has occasioned a smoky exhaust. This has largely been due to the driver fully depressing the accelerator pedal at low speeds; in consequence, an excessive quantity of oil has been injected, corresponding to an unduly rich mixture.

Drivers are now being taught that such methods hinder rather than help smart acceleration. In addition, mechanical steps to check the evil have been taken. As a rule, these take the form of providing a limit stop to the pump control, so that no more fuel can be supplied than is really required to give maximum power in an engine of the capacity in question.

Improved control of the combustion process, particularly of the initial stages, has enabled knocking to be very much diminished. Credit in this matter is also due to the fuel suppliers, who have improved the specifications of their products in such a way as to shorten the delay period which occurs between the beginning of injection and the rapid pressure rise of the initial combustion.

While on the fuel topic, it is worth pointing out that greater efficiency is now obtained by many who have learned the ultimate economy of paying a fair price for clean oil fuel of a known quality. Passing the fuel through a centrifugal purifier removes a surprising amount of impurity, frequently due to dirty storage tanks ; this precaution not only prevents atomizer choking, but tends to give a cleaner exhaust.

This system also reduces liner wear. Much has been done in this direction by the use of hardened cylinder barrels, centrifugally cast sleeves, and of hardened and tempered piston rings.

As the oil engine became more popular, the lubricant suppliers gained experience of the problems that were encountered, and they are now able to provide oils which suffer less from sludging and dilution. Combustion improvements have greatly reduced the dilution of sump oil.

These technical advances on the part of engine makers and suppliers of fuels, lubricants and auxiliaries, have resulted in the production of a class of prime-mover which has now come to be regarded in many quarters as being less subject to failures than its competitor.