ADVANCES in BRITISH VEHI( DESIGN for Home and Overseas I T

Page 80

Page 81

Page 82

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

is doubtful whether a casual observer would be impressed by an .nspection,. for the purpose of making a comparison, of an up-to-date chassis and a chassis produced two years ago. In general line, shape and, indeed, specification, there is little apparent difference, but, if one • delves more closely into the design, many changes for the better can be observed, a matter of importance being the fact that practically every component in the layout of all types of chassis is affected.

Thus, it is impossible to point to, say, a power unit and to state that a striking advance has been made in the design of this component, to the exclusion of axles, frames, steering gear, transmission, electrical equipment and so forth. Consequently this review must deal essentially with every chassis component, and the layout of each particular item must be examined closely in order to detect changes in design, the sum total of which has made such a difference to the performance and general road characteristics of British vehicles.

One naturally starts a review of this kind with a consideration of the main structure of a chassis—the frame. It is quite easy, in superseding any design, to make a stronger frame than previously, but in commercial vehicles this is not sufficient, for, hedged in by regulations and heavily taxed, operators are not unjust in their demand for a sensibly large pay-load space and light ness in weight—characteristics which are diametrically opposed and offer considerable difficulty to designers.

During the past year the matter of weight reduction has been taken seriously into consideration and, in at least one instance, it has been found possible to produce a vehicle capable of dealing with 5-ton loads, yet weighing but 2-i tons itself.

Naturally enough, the light weight of the frame is not entirely responsible for this state of affairs, but it must beadmated that to produce such a vehicle is no mean achievement. The capacity of the frame, although ample for all practical purposes, is' not accompanied by excessively heavy side or cross-members. Deep channels of relatively thingauge material have taken the place of heavy-sectioned shallow girder types of frame, and it is worth recording that the capacity of the new types for resisting lozenging, weaving and be,nding stresses is greater in the new than in past models.

Another-point, the flitchine• of frame structures has been improved out of all recognition, with the result that localized stressing is avoided with a consequent reduction in the possibility of failure occurring at any heavily laden part.

Whilst dealing with improvements in design, it is impossible to dissociate one's thoughts from the rapid development of the oil engine for use in commercial vehicles. Although power-units which run on petrol are doubtless produced in far greater quantities, the advantages offered by the oiler for special classes of work are so important that they must be mentioned. When used abroad, vehicles often have to under take long joarneys across undeveloped country, where fuel supplies are inadequate for the needs of a regular service. Accordingly special consideration has to be given to tank capacity and the range of action of any specific vehicle.

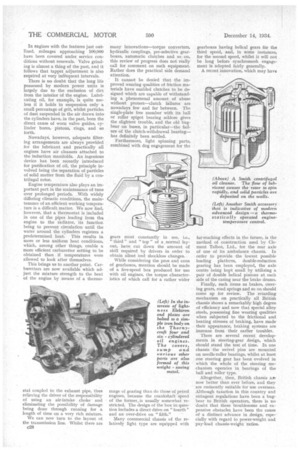

For short journeys the oil engine holds no great advantage over its petrol counterpart, except in so far as cost of operation is concerned, but where distances of 500 miles and more have to be covered, the proposition becomes different. Among accompanying illustrations will be found graphs depicting

the relative weights and fuel costs of two hypothetical 6tonners, one powered by a petrol .engine and the other equipped with an oil engine, the calculations concerning the former type being based on a consumption rate of 6 m.p.g, and, for the latter type, of 11 m.p.g. The weight ratio of the petrol engine is assumed to be 11.5 lb. per b.h.p. and that of the oiler 13.5 lb. per b.h.p., whilst in computing the total weight of the unit, the higher torque characteristics, at low and moderate speeds, of the latter type have led us to choose SO b.h.p. for the output of the petrol engine and 70 b.h.p. for the compression-ignition unit in order to get an exactly comparable basis.

One set of curves indicates the weights of fuel required for distances from 0 to 1,000 miles, whilst another is plotted from the sums of the engine weights and fuel weights. It will be seen that, after allowing for the additional weight of the oil engine, there is an advantage to be obtained in the matter of weight over the petrol counterpart for distances exceeding 250 miles between refuelling, and that at 800 miles there is over 250 lb. in favour of the former type of unit. The difference in the cost of operation, of course, is great, being no less than 17 10s.

With a gradual increase in thermal and volumetric efficiencies there has been a good deal of speculation as to the wearing qualifies of the latest type of engine. We have no hesitation in saying that modern units are incomparably better in this respect than they were a few years ago. Such items as centrifugally, cast, hardened cylinder liners, special alloy pistons with a high Brinnel figure and a low expansion rate when subjected to heat, have combined to give a greatly improved life to engines generally and, at the same time, to minimize oil consumption.

Again, valve seats are, in many instances, made in rings of special centrifugally cast iron and inserted in the cylinder blocks, a patented system. whereby a deposit of Stellite—an extremely hardmetal—is fused to the ring to form the actual valve seating, being a recent development.

KEY TO CHASSIS DRAWING ON RIGHT

1—Automatic chassis lubrication.

2—Needle-roller propeller-shaft joints. 3—Nitralloy-steel brake drums. 4-Centrifugal oil cleaner. 5—Thermostatically controlled engine cooling, 6—five-speed gearbox for oil-engined vehicles.

7—Built-in fuel and oil filters, 8-Carbon-ring glands for water pumps. 9—Centrifugally cast, hardened, iron cylinder liners.

10—Aluminium pistons with low expansion rate. • 11—Air cleaner.

I2—A 24-volt. starter-motor for oilers. 13—Long-life friction facings for clutches and brakes.

14—Rubber-insulated engine mountings. 15-0illess bushes for articulating shafts. I6Silentbloc bushes for spring eyes. • 17—Constant-voltage dynamos. 18—Electric wiring enclosed in armoured casings.

19—Rubber-insulated radiators. 20—Aluminium alloy, Elektron or Hidu • minium for crankcases and Cylinder blocks.

21—Vacuum-assisted braking, 22-14ydraulic application of brakes. 23—Auxiliary loading leaves to rear springs.

24—Medium-pressure tyres.

25—Battery master switch. • 26—Built-in exhauster for vacuum braking. 27-:--Governor for idling and maximum engine speed. 28—Central support for marn and auxiliary shafts In gearboxes: ball and roller bearings throughout.

29—Ball or roller-bearing clutch spigot. 30—Gearbox and rear-axle filler spouts at correct oil level.

31—Ample flitching to franie cross-bracing. direction indicators. In engines with the features just outlined, mileages approaching 100,000 have been covered under service conditions without renewals. Valve grinding is almost a thing of the past, and it follows that tappet adjustment is also required at very infrequent intervals.

There is no doubt that the long life possessed by modern power units is largely due to the exclusion of dirt from the interior of the engine. Lubricating oil, for example, is quite useless if it holds in suspension only a small percentage of grit, whilst particles of dust suspended in the air drawn into the cylinders have, in the past, been the direct cause of worn valve guides, cylinder bores, pistons, rings, and so forth.

Nowadays, however, adequate filtering arrangements are always provided for the lubricant and practically all engines have air cleaners attached to the induction manifolds. An ingenious device has been recently introduced for purification of oil, the principle involved being the separation of particles of solid matter from the fluid by a centrifugal rotor.

Engine temperature also plays an important part in the maintenance of tune over prolonged periods. With widely differing climatic conditions, the maintenance of an efficient working temperature is a difficult matter. We now find, however, that a thermostat is included in one of the pipes leading from the engine to the radiator, its function being to prevent circulation until the water around the cylinders registers a predetermined heat. This results in more or less uniform heat conditions, which, among other things, enable a more efficient carburetter setting to be obtained than if temperatures were allowed to look after themselves.

This brings us to another point. Carburetters are now available which adjust the mixture strength to the heat of the engine by means of a thermo

stat coupled to the exhaust pipe, thus relieving the driver of the responsibility of using an air-intake choke and eliminating the possibility of damage being done through running for a length of time on a very rich mixture.

We can now turn to the layout of the transmission line. Whilst there are

many innovations—torque converters, hydraulic couplings, pre-selective gearboxes, automatic clutches and soz on, this review of progress does not really call for comment on such equipment. Rather does the practical side demand attention.

It cannot be denied that the improved wearing qualities of friction materials have enabled clutches to be designed which are capable of withstanding a phenomenal amount of abuse without protest—clutch failures are nowadays few and far between. The single-plate free member with its ball or roller spigot bearing seldom gives the slightest trouble, and the old bugbear on buses, in particular—the failure of the clutch-withdrawal bearing— has definitely been settled.

Furthermore, light spinning parts, combined with dog engagement for the gears most constantly in use, i.e., " third " and " top " of a normal layout, have cut down the amount of skill required by drivers in order to obtain silent and shockless changes.

While considering the pros and cons of gearboxes, mention should be made of a five-speed box produced for use with oil engines, the torque characteristics of which call for a rather wider range of gearing than do those of petrol engines, because the crankshaft speed of the former, is usually somewhat restricted. The design of the box in question includes a direct drive on " fourth " and an over-drive on "fifth."

*any commercial chassis of the relatively light type are equipped with

gearboxes having helical gears fdr the third speed, and, in some instances, for the second speed, whilst it will not be long before synchromesh engagement is adopted fairly generally.

A recent innovation, which may have far-reaching effects in the future, is the method of construction used by Clement Talbot, Ltd., for the rear axle of one of its ambulance chassis. In order to provide the lowest possible loading platform, double-reduction gearing has been employed, the axle centre being kept small by utilizing a pair of double helical pinions at each side of the casing near the brake drums.

Finally, such items as brakes, steering gears, road springs and so on should come up for review. The retarding mechanism on practically all British chassis shows a remarkably high degree of efficiency and now that special alloy steels, possessing fine wearing qualities when subjected to the frictional and heating stresses of braking, have made their appearance, braking systems are immune from their earlier troubles.

There are several recent developments in steering-gear design, which should stand the test of time. In one chassis the swivel pins are mounted on needle-roller bearings, whilst at least one steering gear has been evolved in which the whole of the steering mechanism operates in bearings of the ball and roller type.

Altogether, then, British chassis now better than ever before, and they are eminently suitable for use overseas. Although taxation in this country and stringent regulations have been a bugbear to British operators, there is no doubt that these troublesome and expensive obstacles have been the cause of a distinct advance in design, especially with regard to power-weight and pay-load chassis-weight ratios.