a winner — if o•erators can 'usti its 'rice.

Page 37

Page 38

Page 39

Page 40

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

• Step forward if you reckon you need a 208kW (279hp) six-wheeler. You might find yourself with more company than you expected. According to Iveco Ford, 30% or more of six-wheeler operators now want more than 180kW (241hp) at 24.39 tonnes. As with most weight classes, the demand for greater power is on the increase — only five years ago just 2% of the six-wheelers sold offered engine power above this level.

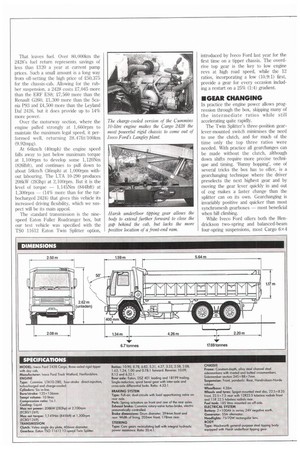

The 2428, the latest in a line of Cargo six-wheelers, is the largest and most powerful rigid chassis ever produced at lveco Ford's Langley plant. Sales of 6x4s appear to be holding up better than for the larger multi-wheelers, despite a 30% downturn in the six-wheeler market. Sixwheeler sales are beating eight-wheelers by 30%, yet only a year ago, with much larger volumes, the reverse was true.

Iveco Ford's share of the six-wheeler market has almost doubled in the past four years, largely due to the acceptance of the Cummins C-Series engine used to power the 2421, but also due to the Cummins LT10, rated at 186kW (250hp) being specified for the Cargo 2424.

The 9.6-litre air-cooled Deutz vee-six engine, which has been available for the past eight years, will eventually disappear from the specification sheet now that the C-Series engine also offers a Knowles PTO at about 150kW (200hp).

It might be supposed that more power means more weight. In fact charge-cooling the Cummins 10-litre engine adds just 20kg to the turbocharged version, but the 2428 is 516kg heavier than the less powerful 2421.

Iveco Ford is not alone in offering highpowered six-wheelers, but of nine makers competing in the six-wheeler sector, only ERF and Foden offer more power.

The attraction of high power is the promise of performance with economy — if the weight penalty is marginal, that's a bonus. As most tippers still operate locally, there is the chance that quicker journey times might allow an extra load to be carried in a working day, depending on the nature of the terrain.

• PERFORMANCE

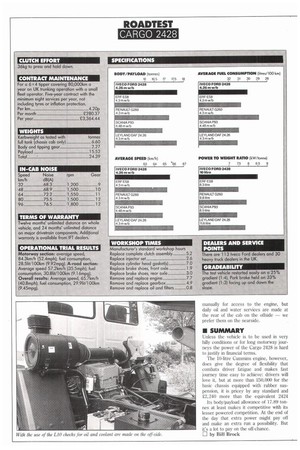

Over the relatively easy terrain of the CM tipper route, the Cargo 2428 is marginally quicker than most of the lower-powered vehicles in our comparison charts, but savings of less than lkrniti over a ninehour driving day must be seen as only of limited benefit. If A-road running is looked at in isolation then the evidence suggests even less of an advantage.

While the 2428 remains competitive on payload, at 390kg above the average in our comparison, 240kg of that is due to the light Hendrickson-Norde rubber suspension, so there's little advantage one way or the other here unless the alternative is for much less power. That leaves fuel. Over 80,000km the 2428's fuel return represents savings of less than £120 a year at current pump prices. Such a small amount is a long way from off-setting the high price of £50,375 for the chassis-cab. Allowing for the rubber suspension, a 2428 costs 27,045 more than the ERF ES8; 27,560 more than the Renault G260, 21,300 more than the Scania P93 and .24,500 more than the Leyland Daf 2426, but it does provide up to 14% more power.

Over the motorway section, where the engine pulled strongly at 1,660rpm to maintain the maximum legal speed, it performed well, returning 28.471it/100km (9.92mpg).

At 64km/h (40mph) the engine speed falls away to just below maximum torque at 1,100rpm to develop some 1,120Nm (826Ibft), and continues to pull down to about 58km/h (36mph) at 1,000rpm without labouring. The LTA 10-290 produces 208kW (283hp) at 2,100rpm. But it is the level of torque — 1,145Nm (8441bft) at 1,300rpm — (14% more than for the turbocharged 2424) that gives this vehicle its increased driving flexibility, which we suspect will be its main appeal.

The standard transmission is the ninespeed Eaton Fuller Roadranger box, but our test vehicle was specified with the TS0 11612 Eaton Twin Splitter option, introduced by Iveco Ford last year for the first time on a tipper chassis. The overdrive top gear is the key to low engine revs at high road speed, while the 12 ratios, incorporating a low (10.9:1) first, provide a gear for every occasion including a restart on a 25% (1:4) gradient.

• GEAR CHANGING

In practice the engine power allows progression through the box, skipping many of the intermediate ratios while still accelerating quite rapidly.

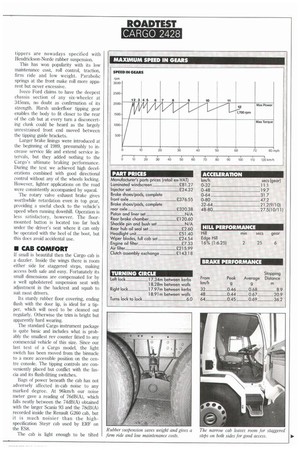

The Twin Splitter's three-position gearlever-mounted switch minimises the need to use the clutch, and for much of the time only the top three ratios were needed. With practice all gearchanges can be made without the clutch, although down shifts require more precise technique and timing. 'Bunny hopping', one of several tricks the box has to offer, is a gearchanging technique where the driver preselects the next highest gear and by moving the gear lever quickly in and out of cog makes a faster change than the splitter can on its own. Gearchanging is invariably positive and quicker than most synchromesh gearboxes — most beneficial when hill climbing.

While Iveco Ford offers both the Hendrickson two-spring and balanced-beam four-spring suspensions. most Cargo 6x4 tippers are nowadays specified with Hendrickson-Norde rubber suspension.

This has won popularity with its low maintenance cost, roll control, traction, firm ride and low weight. Parabolic springs at the front make roll more apparent but never excessive.

Iveco Ford claims to have the deepest chassis section of any six-wheeler at 345mm, no doubt as confirmation of its strength. Harsh underfloor tipping gear enables the body to fit closer to the rear of the cab but at every turn a disconcerting clunk could be heard as the largely unrestrained front end moved between the tipping guide brackets.

Larger brake linings were introduced at the beginning of 1989, presumably to increase service life and extend service intervals, but they added nothing to the Cargo's ultimate braking performance. During the test we achieved high decelerations combined with good directional control without any of the wheels locking. However, lighter applications on the road were consistently accompanied by squeal.

The rotary valve exhaust brake gives worthwhile retardation even in top gear, providing a useful check to the vehicle's speed when running downhill. Operation is less satisfactory, however. The floormounted button is located too far back under the driver's seat where it can only be operated with the heel of the boot, but this does avoid accidental use.

• CAB COMFORT

If small is beautiful then the Cargo cab is a dazzler. Inside the wings there is room either side for staggered steps, making access both safe and easy. Fortunately its small dimensions are compensated for by a well upholstered suspension seat with adjustment in the backrest and squab to suit most drivers.

Its sturdy rubber floor covering, ending flush with the door lip, is ideal for a tipper, which will need to be cleaned out regularly. Otherwise the trim is bright but apparently hard wearing.

The standard Cargo instrument package is quite basic and includes what is probably the smallest rev counter fitted to any commercial vehicle of this size. Since our last test of a Cargo model, the light switch has been moved from the binnacle to a more accessible position on the centre console. The tipping controls are conveniently placed but conflict with the fascia and its flush-fitting switches.

Bags of power beneath the cab has not adversely affected in-cab noise to any marked degree. At 96km/h our noise meter gave a reading of 76dB(A), which falls neatly between the 74dB(A) obtained with the larger Sc,ania 93 and the 78dB(A) recorded inside the Renault G260 cab, but it is much noisier than the highspecification Steyr cab used by ERF on the ES8.

The cab is light enough to be tilted manually for access to the engine, but daily oil and water services are made at the rear of the cab on the offside we prefer them on the nearside.

• SUMMARY

Unless the vehicle is to be used in very hilly conditions or for long motorway journeys the power of the Cargo 2428 is hard to justify in financial terms.

The 10-litre Cummins engine, however, does give the degree of flexibility that combats driver fatigue and makes fast journey time easy to achieve: drivers will love it, but at more than £50,000 for the basic chassis equipped with rubber suspension, it is pricey by any standard and £2,240 more than the equivalent 2424

Its body/payload allowance of 17.89 tonnes at least makes it competitive with its lesser powered competition. At the end of the day that extra power might pay off and make an extra run a possibility. But it's a lot to pay on the off-chance. 1=1 by Bill Brock